The Viking Women With Intentionally Reshaped Skulls

Scientists posit how and why the ladies achieved the cone-head look.

Filing teeth is not exactly unheard of in ancient societies. The Vikings were known to carve grooves into their incisors for status or intimidation, similar to the Maya of Central America and Zappo Zap people in Congo, among others. But while examining Viking skulls from the island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea, a team of researchers also found another deliberate body modification, one that’s much more extraordinary.

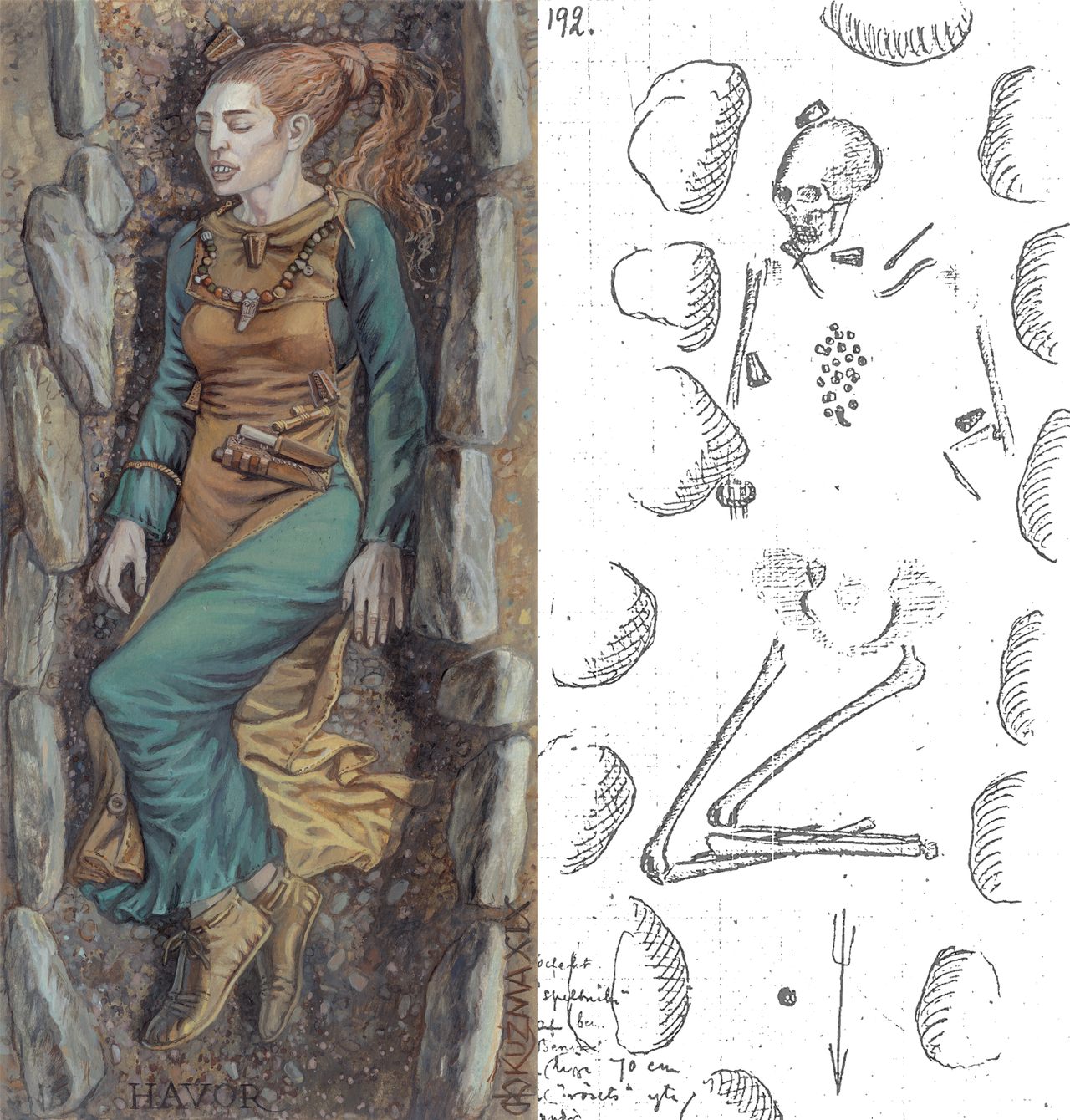

Three skulls had been subjected to cranial modification to achieve an oblong shape. The skulls belonged to adult women who lived approximately 1,000 years ago. Led by Matthias Toplak of the Viking Museum Haithabu and Lukas Kerk of the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, the team published their recent discovery in the Current Swedish Archaeology. Toplak says the finding sheds new light on how Viking groups interacted with other civilizations.

Cranial modification has been seen in various parts of the world, and is still practiced in some isolated cultures today. But artificial cranial deformation had never been previously linked to Viking culture before this discovery. Toplak and his team hypothesize that the practice was likely picked up during trade travels.

“We do not know where these three women grew up and where their heads were deformed,” he explains in an email—but they were Viking women. DNA analysis reveals that they were originally from the Baltic Sea area. “Whether their heads were deformed in their early childhood in the region around the Black Sea, for example, and how they came back to Gotland is unclear,” Toplak writes. The Black Sea region practiced cranial malformation regularly.

These particular skulls were elongated, which was generally accomplished by wrapping bandages around an infant’s head while the bones are still malleable. Today’s physicians are focused on correcting misshapen infant skulls caused by deformational plagiocephaly, but at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Chief of the Division of Pediatric Plastic Surgery Jesse Goldstein says he and his colleagues have long been interested in the historical practices that sought just the opposite.

“Cranial modification has long piqued the interest of anthropologists and craniofacial surgeons,” says Goldstein. “Modifications have been recorded in various cultures throughout history, including the Mesoamerican, Native American, Eurasian, and now, Viking people.”

The process of deforming a skull a thousand years ago, says Goldstein, was likely not that different from the process his team uses to shape a skull today. Modern babies are fitted with plastic helmets that slowly reshape flat spots and other deformities over months as their brains grow. Many historical cultures have used bandages to slowly deform skulls in much the same manner.

These types of passive modification do not affect cognition or development, though Goldstein says more aggressive cranial modification techniques—such as actively pushing on the skull with weights or straps—could apply undue pressure to the brain. “If this approach was taken, this may have had negative effects on brain function, especially if this was employed in early infancy. It is hard to know for sure.”

While skulls alone cannot tell researchers anything about the cognitive function of these three adult women, they do tell us so much more about how practices move between cultures and about what they signify.

Their cone-shaped skulls were likely a sign of status, says Toplak. “We do not think that they were perceived as members of a royal elite on Gotland because of their deformed skulls, but rather that they were a symbol of far-reaching trade contacts and commercial success due to their exotic appearance.”

These women living in Gotland with their distinctive head shapes clearly stood out from fellow Vikings who had not had the opportunity to travel abroad and interact with varied cultures.

“It is still not entirely clear whether the deformed skulls were intended to symbolise [sic] a certain ideal of beauty or whether they were intended to express membership of an elite or a particular social group,” writes Toplak. “It is possible that all these aspects came together and the deformed skulls were an expression of a social elite and thus signalled [sic] status and, inevitably, attractiveness.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook