Swallow-Songs for Spring Are the Greek ‘Trick or Treat’

It’s a tradition that goes back centuries.

More than 2,000 years ago, on the first day of spring, children raised their voices in song across the Greek island of Rhodes. They traveled in groups from house to house as they sang, asking for gifts to celebrate the springtime return of the migratory swallow. The Swallow-Song of Rhodes, like trick-or-treating at Halloween, playfully threatened mischief if the children were not given a treat. But the lyrics suggest that it was all in good fun; that opening your door to give the carolers whatever morsel you could spare was part of the joyous atmosphere of the season.

Remarkably, you don’t have to go back in time to witness the custom of the swallow-song today. An internet search for chelidonisma (meaning “swallow-ing,” as in swallow, the bird) will turn up videos of modern Greek children waving paper swallows and gleefully singing off-key. In a paper on the custom, Greek literature scholar Panagiotis Roilos wrote that in Greece, children have been singing swallow-songs “from antiquity to the Middle Ages to modern times.”

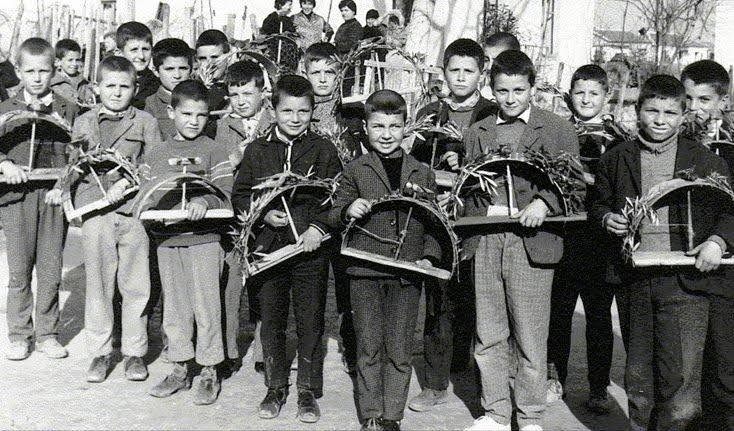

Swallow-songs come from various regions of Greece, such as Thrace, Thessaly, and the Dodecanese Islands. The lyrics and melody of the songs vary, but they share more similarities than differences. “Another swallow came, sat, sang, and sweetly chirped: ‘March, my good March!” go the words of a swallow song still sung today. In the same song, the children call on the “good housewife” to “enter your cellar, bring partridge eggs and lean birds” as food offerings. Though the custom was historically practiced only by boys in some communities, contemporary versions often have both boys and girls participate.

According to Panagiotis Kambanis, an archaeologist and historian at the Museum of Byzantine Culture in Thessaloniki, Greece, “today’s swallow songs are a continuation of the New Year carols of March 1 of the ancient Greeks.” He explains that, after 46 BC, when the Roman Empire established January 1 as the New Year, Greeks and the later Byzantines continued to celebrate March 1 as the first day of spring. “The Byzantines, no matter how faithful Christians they were, did not separate themselves from the ancient Greek and Roman festive customs,” says Kambanis. Swallow-songs were just one of the many customs with pagan origins that endured in medieval Christian Greece. The longest and most-complex surviving example of Byzantine folk music, in fact, is a swallow-song written down in the 12th century.

Long before that, the ancient author Athenaeus recorded the lyrics of the Swallow-Song of Rhodes in his third-century text Deipnosophistae, which can be translated as “The Learned Banqueters.” Written as a series of rambling dinner conversations, Deipnosophistae is a cultural encyclopedia of ancient Greece, peppered with quotations and references dating back centuries. At one point, Athenaeus’s learned banqueters turn to the subject of songs sung by beggars collecting alms, such as the Swallow-Song of Rhodes.

The banqueters compare the Swallow-Song to an unrecorded song used by “crow-men.” Scholars know very little about these crow-songs, and it’s unclear if children also participated in them. Classics scholar Antonio Genova has suggested that crow-songs might have been “the autumnal or winter equivalents” to the spring tradition of the swallow-song.

How exactly the custom of singing the swallow-song emerged is unknown. The ancient Greek scholar Theogonis claimed that an enterprising politician in the city of Lindos came up with the idea of using the song to gather donations “when there was a need in that city of a collection of money,” though Antonio Genova considered this probably false. More likely, the custom is connected to the symbolic resonance of the swallow itself, which Kambanis explains has a long history of positive associations in many parts of the world. “Swallows have always symbolized love, loyalty, and devotion because they form monogamous couples,” says Kambanis. They also represent freedom, home, happiness, and even the human soul in Greek tradition.

It’s easy to see how swallows might have become a happy herald of the warming weather, especially given their tendency to return to the same nest year after year. The swallow-song also parallels other seasonal European folk traditions surrounding birds, such as the “wren-songs” of the British Isles, sung by groups of boys during winter well into the modern era. As they knocked on doors, “wren-boys” carried the tiny body of a wren they had killed and demanded offerings for the funeral expenses, with lyrics like “Give us a penny to bury the wren!”

Unlike the wren-song, no swallows are harmed in the singing of a Greek swallow-song, and when the singers carry birds, they are artificial. One elaborate historical contraption resembled a cage, with a wooden swallow inside that the operator “could rotate left and right by pulling a string,” says Kambanis. Other versions are simpler, consisting of a swallow on a stick, and today, swallows are also cut out of paper.

Traditionally, the swallow cage was decorated with flowers and leaves, as well as red-and-white threads called martes. These were woven by the mothers of the boys, and believed to bestow protection. Similar red-and-white threads also feature in the springtime celebrations of other European cultures. According to Kambanis, the swallow-boys would pass out the martes “as a gift for the little girls in the house.” Once gifted the martes, girls would wear them as a necklace or bracelet for the next 40 days. Afterwards they would hang the threads outside for the swallows to take for their nests, or place them beneath a stone for a form of divination: “to see after a few days, depending on the findings under the stone, if they would marry in the village or in the city,” says Kambanis. He notes that the custom dates back at least to the 5th century.

Though Athenaeus only references it in passing, the Swallow-Song of Rhodes has long captivated historians because it represents one of the only surviving examples of folk music from ancient Greece, as well as a rare glimpse into ancient Greek childhood. It’s also long been a point of fascination for scholars seeking to trace the ancient origins of modern Greek customs. In the 1980s, ethnomusicologist Samuel Baud-Bovy recorded contemporary swallow-songs as part of his survey of Greek folk music traditions, and even recorded a reconstruction of the ancient Swallow-Song of Rhodes. Baud-Bovy believed that, since the lyrical content of swallow-songs has changed little over time, the meter and rhythm of modern swallow-songs might also have stayed the same, though he wrote that he was “not so naïve as to imagine” that his reconstruction was a perfect rendition of the ancient tune.

Kambanis says that today, the swallow-song is not known “as much as it should be.” However, “the custom is slowly being revived in various regions of Greece,” an effort to which Kambanis has contributed. In 2019, Kambanis organized a spring equinox event at the Museum of Byzantine Culture, which featured a performance of swallow-songs sung by a choir. Making swallows and learning a swallow-song has also been used by some teachers in modern Greece as a springtime classroom activity. While the original Swallow-Song of Rhodes is no longer sung, echoes of it remain: an enduring symbol of the cycle of nature.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook