A Surprising Fact About Medieval Europeans: They Recycled

The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore shows us that Medieval Europeans reused parchment, building materials, and even Classical sculptures.

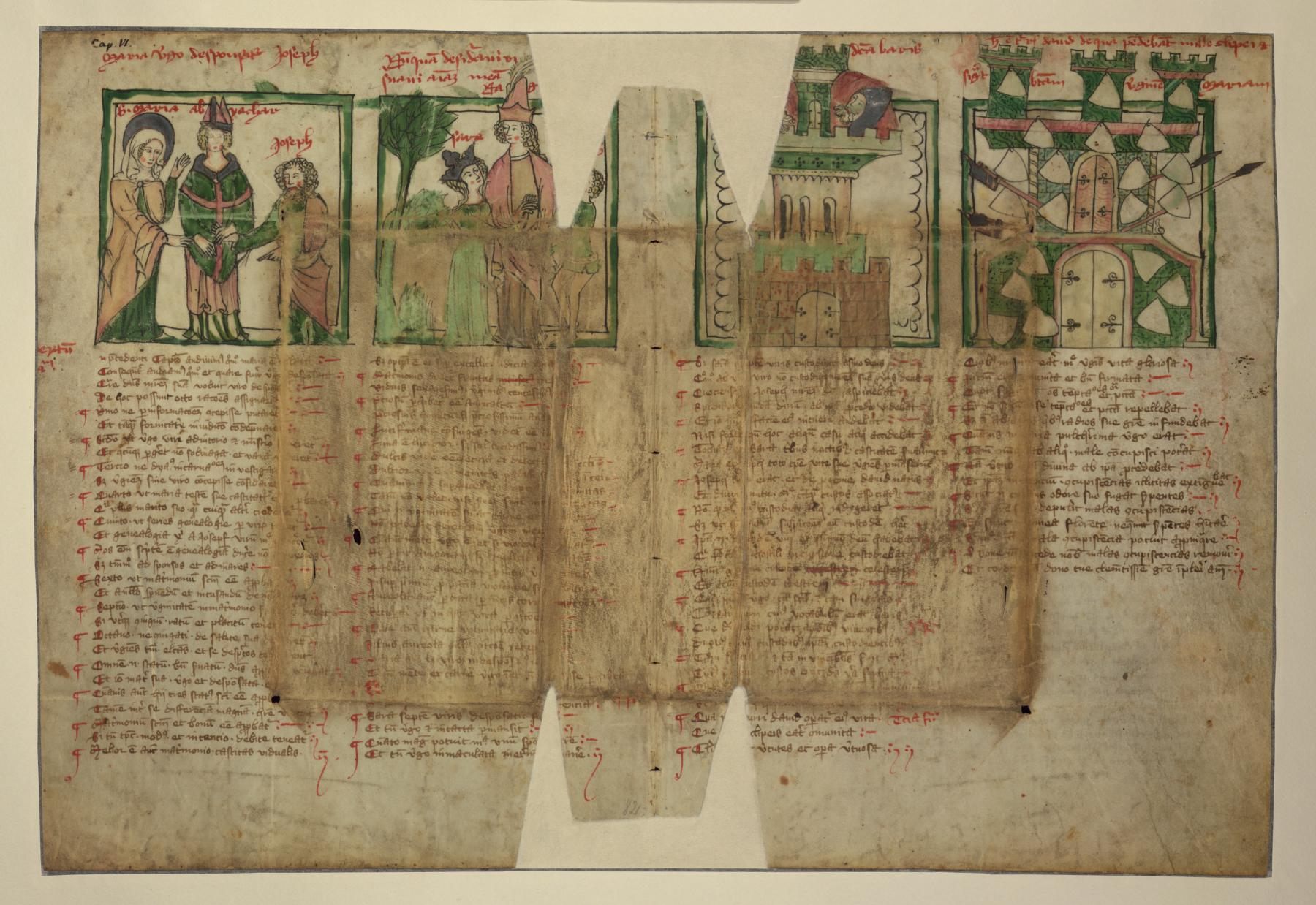

Two leaves from The Mirror of Human Salvation. These pages were reused as a wrapper for a book at some later time. The ghosting of the book it adorned can still be seen in the dark, abraded portion that spans the two pages. (Image: The Walters Art Museum/CC-0)

Next Saturday, Baltimore’s Walters Art Museum will open its newest exhibition, Waste Not: The Art of Medieval Recycling. The exhibit highlights a common medieval practice that isn’t frequently discussed—medieval repurposing of artifacts and manuscripts from earlier eras. As curator Lynley Anne Herbert explains to the Baltimore Sun, “Well, people have been recycling for thousands of years.”

After the Roman Empire collapsed, connections to Asia and North Africa facilitated by the empire’s trade routes broke down, essentially making medieval Europe a smaller, more self-contained place, with less access to new goods and materials. As historian Robin Fleming explained in a 2010 lecture, the decline of the empire was particularly keenly felt in Britain, which was left without industry, trade, or craft when Roman forces abandoned the island in the fifth century. According to Fleming, the British raided Roman ruins for building materials to the extent that until the 11th century, Christian churches in Britain were constructed mostly from scavenged Roman materials. This assertion has been verified through architectural surveys, one of which discovered over 300 churches around London built from Roman ruins. Similarly, tile, ceramics, pottery, and iron were all reclaimed and repurposed.

Additionally, recycling and repurposing of older items occurred on a more personal level. The museum exhibit provides examples of book pages being torn out and used as dust covers for smaller (and apparently more valued) books. In fact, old manuscript pages were frequently recycled in a variety of ways; Dr. Henrike Lähnemann has researched the use of manuscript fragments to line dresses, and medieval book historian Erik Kwakkel has discovered an example of a manuscript—in this case, a 13th-century love poem—being recycled as lining for a bishop’s miter. Herbert told the Sun that manuscripts were particularly likely to be recycled because parchment was expensive and time-consuming to manufacture, and Kwakkel points out in a blog post that the development of the Gutenberg press led to many handwritten books being marked for recycling.

These examples of medieval recycling all fall under the category of items recycled out of frugality, or due to a lack of raw materials, but the exhibit also highlights a different kind of recycling—repurposing objects and materials for ideological reasons.

For example, the Sun discusses the ideological repurposing of a second-century marble bust of Hercules featured in the exhibit. Twelve centuries after the bust was carved, someone apparently decided the bust could be remade into a saint:

“They drilled into his beard to make it appear curlier,” Herbert said. “They also added fine lines and wrinkles to his face, which ages him. He doesn’t look quite as youthful and perfect and beautiful as he did when he was first made, though maybe he looks a little wiser.”

This kind of recycling was hardly an isolated incident. In The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity, Roberto Weiss describes similar repurposing of Roman art, writing, “Sometimes the figures of the consuls carved on them were turned into saints or biblical characters, as happened in a diptych now at Monza, where they became King David and St. Gregory, and in one at Prague, where the consul was transformed into none other than St. Peter himself.” How thrifty!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook