America Almost Had a Disney Theme Park with a Slavery Section

Inside Disney’s America, the doomed ’90s project that almost sunk the company.

Minnie Mouse waves an American flag during a parade at Disneyworld in the 1990s. (Photo: Peter Bischoff/Getty Images)

These days, Disneyland Paris is a global tourist destination, attracting tens of millions of ostensibly happy visitors every year. But when it launched in 1992, the theme park was something else: it was named Euro Disney and it was a flop, threatening to derail the very fabric of a company on a decades-long winning streak. “A cultural Chernobyl,” complained a Parisian theater artist. “This act on the part of America is one of unprecedented violence,” added film critic Serge Toubiana.

This was not part of the plan. In 1989, Eisner had boldly announced the approach of the “the Disney Decade,” a proposal to double shareholder income by aggressively expanding the company’s Parks and Resorts division. At the first shareholders’ meeting in 1990, Eisner announced that Disney would add nearly 50 new attractions to its parks in Florida and California, construct an additional park in Southern California, and, of course, open Euro Disney to the public.

But daily attendance at Euro Disney was less than half of what the company had projected, and the park struggled to service what had ballooned into $3 billion in debt. “Chastened by the rising costs of Euro Disney,” CEO Michael Eisner later wrote in his 1998 autobiography Work in Progress: Risking Failure, Surviving Success, “we began to look for ways to develop smaller-scale theme parks.” A perfect storm erupted: the head of the parks brought Eisner and another c-suite executive to visit Colonial Williamsburg; Eisner “had American history on [his] mind anyway,” and the Imagineer gears were creaking to life to churn out Pocahontas, the 1995 film that was part of the “Disney Renaissance,” a resurgence of the Walt Disney Company’s feature animation program that stretched from 1988 to 1999.

It was in this atmosphere that a project called “Disney’s America” began to take shape.

Walt Disney shows the first Disneyland plans to Orange County officials, December 1954. (Photo: Orange County Archives/CC BY 2.0)

“Building a Disney theme park based on American history seemed like a natural extension of the company’s focus on children and education, a perfect way of marrying our self-interest with a broader public interest,” writes Eisner.

But while Pocahontas might have represented the reinvigoration of the animation unit, no such renaissance awaited company’s Parks and Resorts division. Disney’s America would be one of Disney’s worst ideas and most public failures, a footnote in the company’s official history, one that has been largely forgotten.

The project is worth remembering, though, because while it was a peculiar chapter in Disney’s history, it’s a familiar one in the context of the national struggle to define the public narrative of American history, where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States does battle with sanitized high school textbooks in Texas. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hit musical Hamilton has created a vigorous alternative narrative that rightfully centers men and women of color as America’s builders and inheritors, but it’s still optimistic enough that Lynne and Dick Cheney are among its fans. Disney’s not really to blame for the fact that we’ve retroactively fit U.S. history into a story about the “American Dream.” In this sense, Disney’s America is another slice of the apple pie.

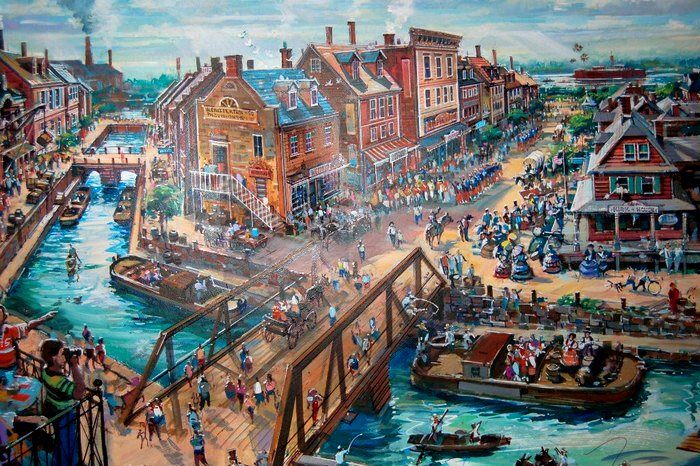

In late 1993, the company issued a press release to unveil the plans for Disney’s America to a patriotic public. Calling the project “a unique and historically detailed environment celebrating the nation’s richness of diversity, spirit, and innovation,” the press release laid forth plans for something that sounds like a cross between the Newseum (another ‘90s museum originally sited in Virginia) and, you know, Disneyland.

Along with animatronic robots of “every American president,” Disney hoped for a facility that could “host and televise political debates, public forums and gatherings of writers, educators, journalists, students and historians to discuss issues of the past, present, and future.” The company bought a 3,000-acre site in Prince William County, Virginia, selected partly because of its proximity to D.C., expecting that tourists to the nation’s capital would be interested in swinging by to see President Mickey after taking in the Lincoln Monument.

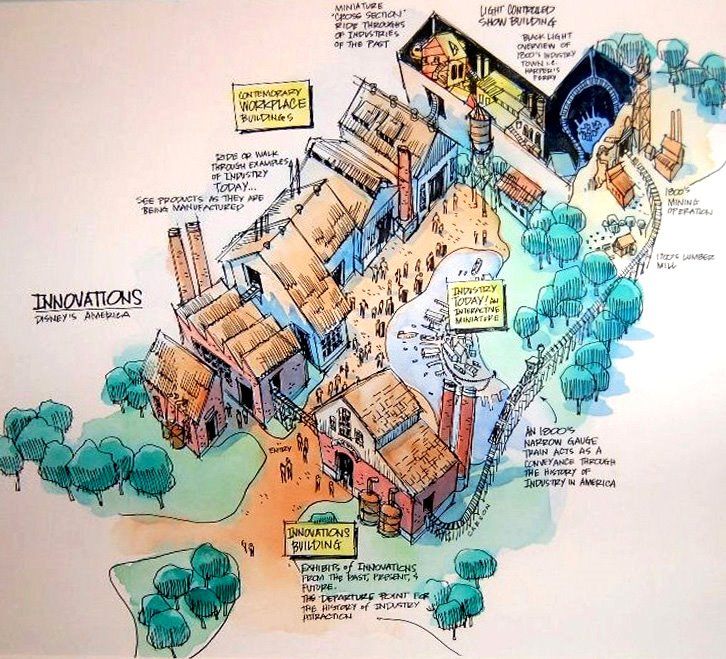

America’s history would be brought to life with entertainment like “a high speed thrill attraction called the ‘Industrial Revolution.’” In launching the project, Disney executives brimmed with enthusiasm. They had reason to be bullish on the concept: The outgoing and incoming governors of Virginia were fully on board with a plan that would bring millions in tax revenue to the state. And the press response was ambivalent but largely positive. “Disney Says Va. Park Will Be Serious Fun,” read one spritely Washington Post headline. (And at this point, most of the critiques had to do with the paucity of whimsical rides, not the weirdness of historical Disneyfication. “Sounds like fun? Sounds like school,” Post columnist Steve Twomey sulked.)

A postcard of the Central Plaza Disneyland Paris, 1994. (Photo: EuroSouvenirland/CC BY 2.0)

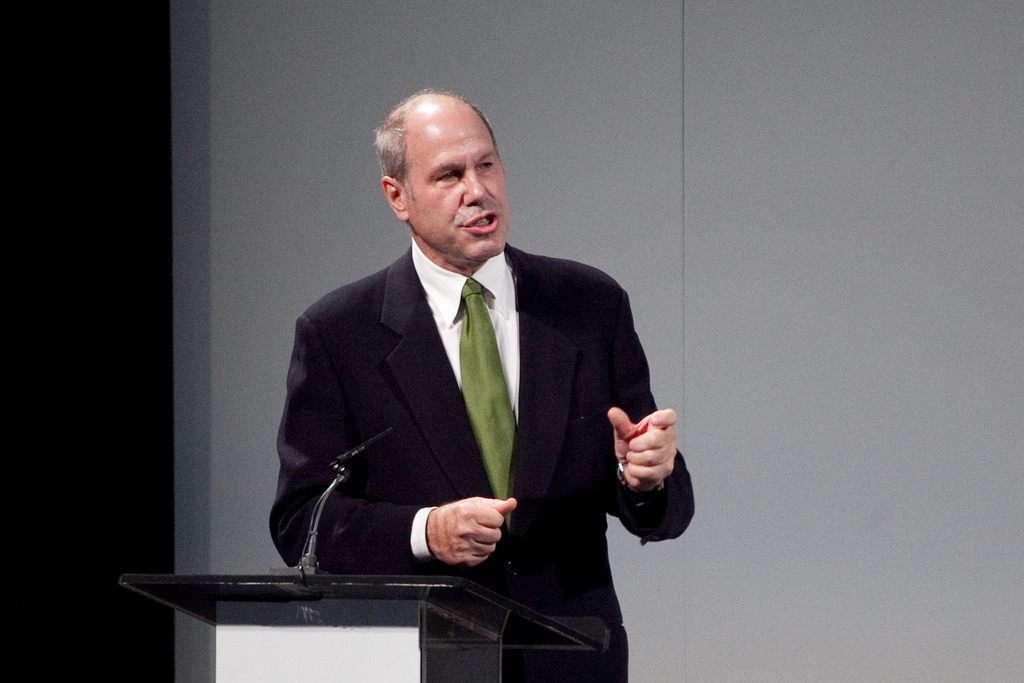

But a mere 11 days after the initial announcement, the park’s narrative began to take a turn. It started when Disney executives held a conference at Walt Disney World in order to unveil their new animatronic Bill Clinton and Abe Lincoln in the Hall of Presidents there. (Abe and Bill were the company’s first talking execubots.) At the press conference, Bob Weis, a senior vice president and the park’s creative director, said, to a room full of reporters, “How can you do a park on America and not talk about slavery? This park will deal with the highs and lows … We want to make you feel what it was like to be a slave, and what it was like to escape through the Underground Railroad.”

This did not go over well.

Beyond the new vision of a Disneyland for slavery, other objections to the project began piling up. One concern was with the likely environmental impact of increased sprawl. The county’s wealthy D.C. power brokers (a cohort that included Jackie Onassis) worried that the project would impinge on the “serenity” of their quasi-rural retreat. A second worry was that the park would draw visitors away from (and fundamentally disrespect) nearby historic and cultural sites ranging from the Smithsonian to Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s estate, and could, critics feared, pull revenue away from already beleaguered nonprofits and trusts. The Washington Post reported that the site was “adjacent to 13 historic towns, 16 Civil War battle sites and 17 historic districts.”

And there was, of course, the fear about making light of American history—and it wasn’t only about cultural symbolism. Disney had chosen property only three miles from Manassas, the site of the war’s first skirmish, the Battle of Bull Run. Ironically, crowds of spectators who expected the war to be light on trauma actually brought picnic baskets to the outskirts of the battlefield and settled in to watch. But what unfolded was the bloodiest, largest battle Americans had fought up to that point. And, a little over a year later, the Second Battle of Bull Run, which was a major blow to Union forces, was bigger and even more mercilessly bloody. Building an enormous historical playland a few miles away from the place where 300,000 men had died was, many thought, a sacrilege.

Michael Eisner in 2010. He wrote “Building a Disney theme park based on American history seemed like a natural extension of the company’s focus on children and education, a perfect way of marrying our self-interest with a broader public interest.” (Photo: Ed Schipul/CC BY-SA 2.0)

The backlash from Bob Weis’s comments about slavery was even worse. Eisner had tried to disavow them—Weis, he said, “is not a person who generally talks to the media”—but Eisner didn’t behave like someone who generally talks to the media, either. In an interview with the Post that December, he didn’t back down on the idea of a slavery exhibit, suggesting first that he thought critics were disingenuous. “I really don’t think they think … (that) to feel like being a slave we’re going to whip them … I don’t know what they could possibly think,” he said. Further, Eisner said,”I read things about this project; it amuses me. I didn’t know we were doing a project about slavery. All of a sudden I’m reading major editorials on slavery. This is not what this project is about.” (He doesn’t acquit himself any better in his autobiography, either: “Within days,” he writes, “critics had seized on this statement as the height of presumption.”)

A parade at Disneyland in 1994. (Photo: Dguendel/CC BY 3.0)

But it wasn’t just the media who found fault. The results of Disney’s focus groups with and surveys of D.C. teens were dismal; they universally agreed that was a bad idea. Washington Post columnist Courtland Milloy hardly trusted Disney to treat the history of slavery with respect, given that “the sons and daughters of the slave masters have managed to manipulate black people so as to portray us as lazy, hateful and unpatriotic.” Washington transportation planner Courtney Gallop-Johnson, who organized the Black History Action Coalition and announced that the group would push for a boycott, told the press, “We don’t think that it is a historically dignified or accurate portrayal, or suitable fare for an amusement park.” She was particularly and reasonably concerned about the possibility of things like “little souvenir slave ships.” Virginia’s governor retorted that Disney should not be bullied into “censorship.” The Wall Street Journal, among other newspapers, quoted Eisner’s response: “We’re not going to put people in chains.”

Then came the historians. Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David McCullough, read by history-buff dads everywhere, had narrated Ken Burns’ 1990 PBS series The Civil War and also hosted American Experience. He was nearly apoplectic about Disney’s America. By the spring of 1994, McCullough, then president of the Society of American Historians, had formed a group to oppose the project. Among the membership of Project Historic America was historian Shelby Foote, who shot to late fame as one of The Civil War’s stentorian talking heads. Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., writer William Styron, and prominent historians of the Civil War, race, and slavery in America—James McPherson, Barbara Fields, C. Vann Woodward, and John Hope Franklin—were part of the effort. Even Burns himself, then actively employed as a consultant for a Disney film about baseball, voiced his opposition to the project.

It only got worse from there. In March, the Post reported that Disney had announced its intention to shift the park’s theme to one built around “American values or cultural themes, which might include diversity, how conflicts have united the country or how Americans have responded to technological change.” Asked Imagineer Robin Reardon, “‘What if we had graduate students doing research on some aspects of American history who would become part of the display?” (Given the misfortunes of the academic job market, this might not have been a bad idea.)

This reframing was certainly in the tradition of American optimism, but it was too late. In June, Protect Historic America held a lively protest at the Washington, D.C., premier of The Lion King (chant of choice: “Take a hike, Mike!”). In July, by which time Project Historic America had over 200 members, the group published an open letter in the New York Times, titled “The Man Who Would Destroy America.” The National Trust for Historic Preservation published one of its own the Washington Post. In her book Battling for Manassas, Joan Zenzen notes that newspapers “throughout the country” produced “more than 10,000 items on the subject.”

Increasingly, pundits took up the historians’ mantle. “With the advent of Disney’s America,” Frank Rich wrote in the Times, “the big bad wolf is standing right outside the door, poised to devour our past.” George Will called Michael Eisner a “Hollywood vulgarian” and suggested that he should follow the example of Confederate general Robert E. Lee and “surrender.”

Leaving Disneyland Hong Kong. (Photo: martinho Smart/shutterstock.com)

Logistical obstacles also mounted. Though the legislature had approved $163 million for public works improvements that would serve the park, the state’s transportation secretary ordered “a full federal review” of the proposed freeway projects, a process that would have taken at least a year and a half. Environmental and citizen groups filed lawsuits. Public support for the park had dropped to 25 percent in national polls. Dale Bumpers (D-AR) convened a Senate hearing on the project. In mid-September, Reuters reported that 3,000 people had “marched on Washington,” chanting “Hey Hey, Ho Ho, Disney’s got to go” while walking from the Washington Monument to the Capitol.

By the end of September 1994, Eisner had announced that Disney was withdrawing from the Virginia site. The ‘90s were rife with canceled or faltering Disney park projects—among them an EPCOT center at Disneyland called WestCOT, and a resort concept, Port Disney. But Michael Eisner pressed on in pursuit of his bold American dream. In 1997, competitor Knott’s Berry Farm, located seven miles up the I-5 from Disneyland, quietly let it be known that the Knott family was interested in selling the park.

The concept drawing for the Industrial Revolution-themed roller coaster. (Photo: © Disney)

Knott’s Berry Farm, as it happened, featured a replica of Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. Could the Imagineers not convert this attraction into President’s Square and renovate the park’s other areas to fit the Disney’s America vision?

But it was not to be: the Knott Family sold to an Ohio-based company instead. Eventually, a few pieces of the concept were halfheartedly built at Disney’s California Adventure, the next project directed by SVP Bob Weis, of the slavery section fame.

The entrance to Knott’s Berry Farm, which the Knott family considered selling in 1997. (Photo: Jeremy Thompson/CC BY 2.0)

Rumblings of Disney America persist, even after all that heartbreak. Last year, a self-described “Pro Republican Blog” reported that the real reason that the board of Virginia’s Sweet Briar College had abruptly announced the institution’s closure was that a silent buyer—guess who?—intended to buy the 3,250 acre campus. “Mickey Mouse,” the post declared, “is trying to kill the Sweet Briar Vixen.” (Court rulings and a multi-million dollar alumnae crowdfunding project saved the school.)

In the end, it was the princesses who offered a path out of the Disney Decade’s darkness. When The Little Mermaid’s Ariel was introduced in 1988, she was the first new Disney Princess since 1959. Between 1988 and 1999, a period that encompassed the rise and fall of Disney’s America, Walt Disney released five animated films that introduced new princesses to the company’s pantheon, and they routinely attract visitors to the parks and accrue billions of dollars of revenue in merchandise and media products for the company.

And the company has turned around the fortunes of Euro Disney, too—first by unveiling the park’s version of Space Mountain, then by renaming it Disneyland Paris and ramping up its resort offerings. Today, the park reports that it attracts more annual visitors than either the Eiffel Tower or the Louvre.

Another concept drawing of the 19th-century themed ‘Crossroads USA’, at Disney’s America. (Photo: © Disney)

Disney’s swing at an American historical theme park wasn’t the first, and probably won’t be the last. In 1960, Cornelius Vanderbilt Wood, whom Walt Disney had fired during the construction of Disneyland, opened Freedomland U.S.A. near the Bronx. You could swig a cool drink in Little Old New York’s Grape Juice Bar, take in a reenactment of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, and, perplexingly, walk through The Old Southwest’s Casa Loca, where the law of gravity did not apply. Freedomland racked up $8 million in debt in just two seasons and limped to a close in 1964.

Yet the Disneyfication of history presses on. In 2009, Disney released The Princess and the Frog, set in 1920s New Orleans. Though the company attracted laudatory praise for introducing Tiana, the first Black Disney princess, the film (Tiana was a frog for most of the movie, which did not depict the reality of racial segregation) and its merchandising (Tiana’s image was used to sell watermelon-flavored candy) attracted blowback in equal measure.

Pop culture has always loved a good American period drama—Mad Men, Outlander, and now recent history like the O.J. Simpson trial have found huge audiences. Now that Hamilton has begun to do battle with The Lion King for the number one spot for weekly gross ticket sales on Broadway, one wonders if Disney is eyeing a return to the past. Could an animatronic Harriet Tubman be next? But the fact is that American history has always been contested, sanitized, and neutralized. If history’s being Disneyfied, it may just be what we the people want.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook