An Exclusive Look at the Leaked PR Agenda of the 1936 Republican National Convention

80 years ago, GOP tactics included “racial choirs.”

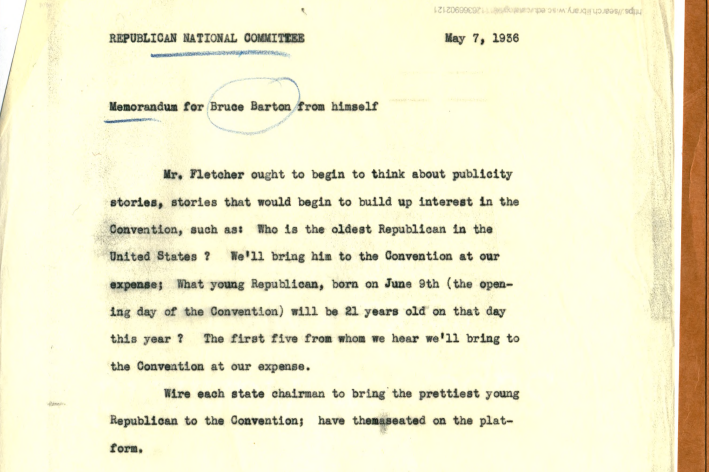

Bruce Barton’s letter to himself ahead of the last time Cleveland held the RNC, 1936. (Photo: Wisconsin Historical Society Archives, Bruce Barton Papers)

“Wire each state chairman to bring the prettiest young Republican to the Convention; have them seated on the platform,” a man named Bruce Barton wrote in a note to himself in 1936. Barton’s ideas were destined for Henry Fletcher, the Chairman of the Republican Party.

That year’s Republican National Convention, to be held in Cleveland, Ohio, was just a month away, and an army of ad men were busily plotting the best ways to reach the electorate. Similarly to today, emphasis was placed on entertainment, appeals to a cross-section of voters, and a show of party unity. Then as now, sometimes-cynical PR tactics were used to achieve these goals.

Barton was a founding partner of the high-profile Manhattan advertising firm BBDO, and during the 1936 campaign season, he lent his public relations skills to the Republican Party. A look at his papers, now part of a collection held by the Wisconsin Historical Society, give insight into the spectacle that is presidential politics today.

The three documents each show something different about the plans made ahead of the convention. Not every item listed during the planning stage came to fruition, nonetheless they indicate how men like Barton thought about political strategy. For instance, even 80 years ago, the Republican Party was making explicit—and not always successful—overtures to minority groups.

African-Americans had traditionally voted for the GOP, but a shift to voting for the Democrats began in the 1930s. In the 1936 election, the Republicans feared the loss of some one million African-American voters. But the ad men had a plan: The New York Times reported prior to the convention that Barton planned to use “racial choirs” to target voting blocs. This included African-American, German, Italian and Scandinavian choirs. The “negro” songs would remind “negro” voters listening on the radio at home that they should vote Republican, reported The Times.

The Republican Party plan the National Convention in Cleveland, 1936. (Photo: Wisconsin Historical Society Archives, Bruce Barton Papers)

Some of the speakers the party officials wanted at the convention represented the demographics of voters the Republican party needed to attract. They were far removed from what people today call the core support base. At the time, the Republican party was largely the party of the affluent. But the convention plan included a woman speaker, a “dirt farmer”, a “young Republican” and a “Constitutional Democrat.”

The papers show how Barton and his peers planned to make the convention memorable for attendees and the people listening in on the radio. In the first letter, dated May 7, Barton considered tactics to please the crowd. He wanted to find the oldest Republican in the U.S. and bring him (it was presumed to be a him) to the convention in Cleveland. Barton also put out a call for any Republicans turning 21 on the day of the convention. He also proposed hiring ”48 good looking girls,” one for each state in the U.S. at that time.

With a background outside of politics, ad men like Barton were valued for their ability to finesse the potential reach of the first form of mass communication: radio. This is because the 1936 election was the first one where parties started to specifically plan their events around a radio audience, and not just the audience in the event hall.

At the time, almost three quarters of American homes had at least one radio. “By 1936 there is a much greater recognition that the audience is really broader than those in the convention hall,” says Adam Sheingate, political scientist at John Hopkins University and author of Building a Business of Politics.

Barton and radio professionals were there to help the party understand how to use the medium in a more sophisticated way. For the first time, speeches at the convention were condensed to be more radio-friendly.

A list of songs for the RNC. (Photo: Wisconsin Historical Society Archives, Bruce Barton Papers)

A calm and skillful presentation over the airwaves certainly made a difference to the audience listening in their living rooms. This was all part of the sale, says Sheingate. And the quality of the entertainment was important too, so the convention needed music.

According to the Barton papers, the GOP wanted to hire Lawrence Tibbetts, a famous singer of the day, or the Cleveland Glee club. At the convention, the Creoleans’ Quartette, a so-called “negro” band, played “Working on the Railroad”—one of the songs listed on a BBDO memo of a recommended list of songs. Fletcher, chairman of the GOP, reportedly endorsed the tune as the party’s official song.

Unfortunately for Barton and the GOP, their carefully made entertainment plans couldn’t sway radio listeners to vote for his party. Franklin Roosevelt went on to win a huge landslide in November for the Democrats—with an unprecedented 71 percent of the black vote.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook