Are We Knitting Too Many Tiny Sweaters for Animals?

Examining the enthusiasm for interspecies knitwear.

Rhea Eisenmann of Boston, Massachusetts, probably has more sweaters than you do. At last count, she had 110 of them, including a bright turquoise pullover with an orange-bordered hood, a felt jumper, and a crocheted* facsimile of a New England Patriots jersey. She models them almost daily on her Instagram, and has been featured sporting them everywhere from Buzzfeed to Fox News.

Rhea is not a cold-intolerant Beacon Hill socialite—she is a two-year-old lovebird who happens to be bald. Rhea has Psittacine Beak and Feather Disease, a condition that attacks bird follicles and causes total feather loss. Her human companion, Isabella Eisenmann, has been raising awareness about the disease through a suite of popular social media profiles, called Rhea the Naked Birdie, filled with nude bird glamour shots.

Last August, the owner of Sock Buddies—a company that makes protective garments for birds who pick out their feathers—sent Rhea a white turtleneck. After Rhea wore it for a photoshoot, “many people started sending me messages about wanting to make her sweaters,” Eisenmann says. So she posted Rhea’s measurements, and the formerly Naked Birdie now gets about a sweater a day.

Eisenmann was, and is, floored by people’s generosity. But perhaps she shouldn’t have been. Across the world, contemporary humans have at least one thing in common—we can’t stop knitting sweaters for animals in need.

You can tell a lot about a society by what its animals are wearing. Although it’s not clear exactly when people began clothing their furry companions, odds are good that the first instances were utilitarian: there’s evidence that Mesopotamian soldiers forged armor for their horses as far back as 2600 B.C., a trend that eventually spread to Greece and Rome.

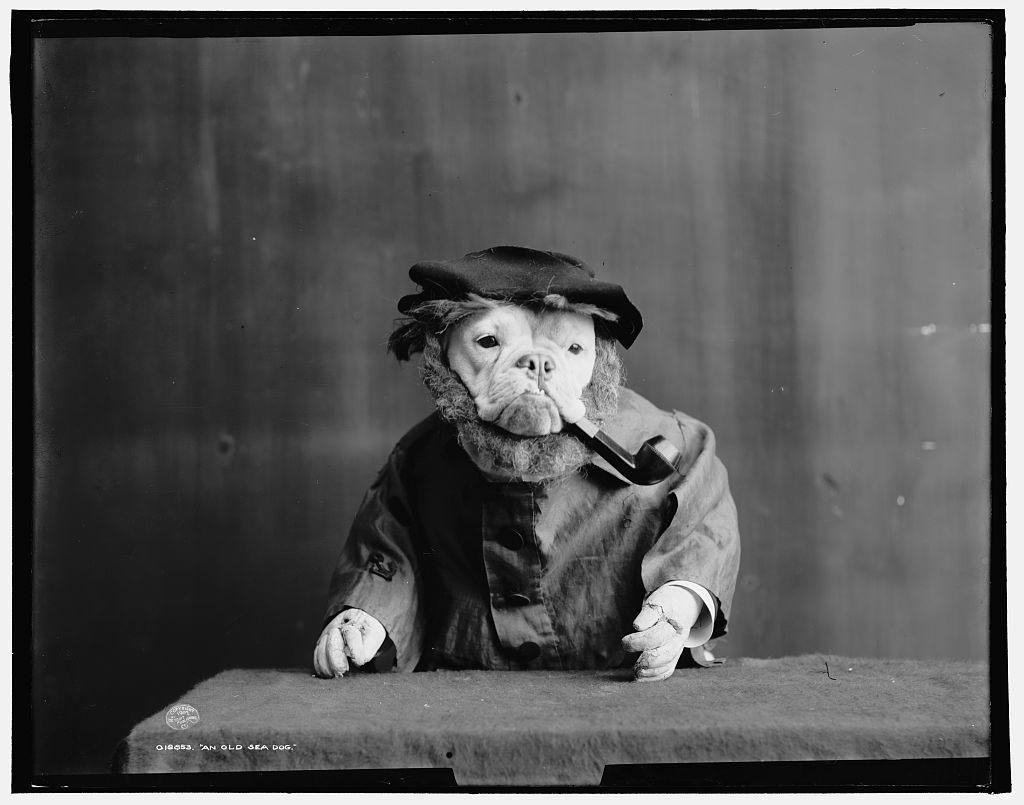

In Victorian times—as animals went from useful tools to beloved family members—socialites enjoyed dressing up their cats and dogs as ladies and gentlemen. And in the hedonistic 1960s, American media prankster Alan Abel got a lot of traction out of the “Society for Indecency to Naked Animals,” a satirical movement that aimed to put clothes on every wild beast “in the name of morality.”

The modern world features an unprecedented number of well-dressed beasts. Designer labels now put out dog clothes. Americans spend hundreds of millions of dollars on Halloween costumes for pets of all sizes, from mice to pigs. A racehorse wearing a three-piece tweed suit and cap made it into GQ, and just this past Friday, two Snuggie-clad goats were found comfortably gallivanting around Idaho. But when future humans look back in time to take our measure, odds seem good they’ll settle on the animal in the hand-knitted sweater.

For starters, relevant examples abound. Let’s begin with the case of the tiny jumpered penguins. In the late 1990s, a series of oil spills off of Australia’s Phillip Island threatened local animals, including the island’s large population of little penguins. Oil is very bad for penguins—it clumps their feathers together, exposing their skin to the cold, and when they try to preen it off with their beaks, it makes them sick.

When rehabilitation teams set out to combat the spill, “[they] found they needed a way to stop penguins preening oil from their feathers while they waited to be washed,” says Lauren Jones, an officer at Phillip Island’s Penguin Foundation. They found knitted jumpers did the trick, and they began soliciting them from local volunteers, through a program they called Knits for Nature.

For years, the Penguin Foundation stockpiled sweaters—“we received a few parcels of jumpers a week,” says Jones. When oil spills occurred, they dipped into the reserves; the rest of the time, the penguins went as God intended. But then, in 2014, a local newspaper profiled Merle Davenport, a long-term volunteer knitter for the Foundation, and the story quickly gained traction worldwide. “A well-meaning journalist took it upon themselves to put out an online call for more jumpers… from that point on we received thousands of jumpers per week,” from every continent, she says. “It was truly incredible.”

Knits for Nature quickly had enough sweaters. By the time the next wave of media attention came around, in 2015, the Pengin Foundation had a PR strategy in place, directing people to other organizations in need of knitted items. Today, if you go to their website, you’ll find a loud disclaimer: “The Knits for Nature program is closed,” it says, in bold italics. “Please note that we do not require any further penguin jumpers at this time.” (If people would like to help the Penguin Foundation, Jones emphasizes, the best thing to do is donate.)

The Penguin Foundation is far from the only group to have unwittingly set off an avalanche of tiny animal clothes. On January 7, 2015, after a rash of bushfires injured dozens of koalas in South Australia, the International Fund for Animal Welfare put out a call for cotton mittens to help the animals’ paws heal. Within two days, they were set for the entire season. One woman from the UK recently quit her job in order to make more jackets and hats for rescue greyhounds. Crafters are perennially knitting sweaters for retired battery hens, even when the need is not immediate.

Even when direct contributions aren’t possible, wool-clad rescue animals get an outsized amount of attention. This past winter, the Wildlife SOS Elephant Conservation and Care Center, in northern India, dressed their pachyderms in giant sweaters to get them through a cold snap. Rather than outsourcing their crocheting to concerned fans, Wildlife SOS taught women from the local Kalandar community to make them, as part of an empowerment initiative.

For a few weeks, you couldn’t surf the internet without running into a picture of an elephant traipsing around in a patterned sweater. “The story definitely garnered a large response [from] supporters and donors,” wrote the organization’s co-founder, Kartick Satyanaryan, in an email.

All of this is extremely understandable. “In this day and age, when so many terrible things are happening, people find comfort in doing things for others,” says Eisenmann. Jones agrees: “There is something very rewarding about sitting down and creating, with your own hands, something that will help another.” And animals in sweaters have a self-evident appeal: they’re cute, they’re ungainly, and—when they’re wild—a snuggly outfit makes them seem suddenly accessible, as though they’ve chosen to be part of our world. And unlike dressing up your dog, clothing a cold bird doesn’t bring down the wrath of the RSPCA, or PETA.

But there may be something more to it than that. A battery hen is naked because she’s spent her life in a tiny cage, laying eggs. A burned koala is suffering the consequences of human-caused climate change. Many naked birds—though not those, like Rhea, with Psittacine Beak and Feather Disease—lose feathers due to stress. Even a besweatered chihuahua is chilly because he’s been moved from his natural habitat, the Central American desert, to a cold New England suburb.

Knitting a sweater for one of these creatures—or an oily penguin, or a cold elephant—can be seen as a fuzzy way of saying “sorry.” That it plays great on Instagram is just a bonus.

Naturecultures is a weekly column that explores the changing relationships between humanity and wilder things. Have something you want covered (or uncovered)? Send tips to cara@atlasobscura.com.

*Correction: This article has been updated, where appropriate, to differentiate between knitting and crocheting.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook