Toilet Brushes Are Partly to Thank for Artificial Christmas Trees

And other strange evergreen decor evolutions, from retro-kitsch to glow-in-the-dark.

In the living room of a home in Missouri, a Christmas tree is shaking of its own accord. The fake trunk and branches of the artificial tree are vibrating, and a swishing noise emanates from the device, which—if you tried very hard to imagine—could sound like sleet hitting the ground. Meanwhile, an angel figure perches at the very top of another tree as tiny Styrofoam balls shoot out from under her skirt, falling through the aluminum branches below before getting collected again from a vacuum-like tray at the bottom. The white foam then circulates back up through a tube, in a continuous flow of fake snow.

“It’s a pain to set up, but it’s quite fun when finished,” says Stephen Pruitt, owner of the devices, when describing the snowing tree. “It’s very, very kitschy, which is exactly why we like it.”

Pruitt and his wife Mary are aluminum tree collectors. They’ve loaned 18 rare and unique aluminum trees to an exhibit at the National Museum of Toys and Miniatures in Kansas City. They own trees that are gold, pink, or even black. But some of their proudest finds include this Bradford Snow Maker, which “guarantees a white Christmas in every home, regardless of climate,” according to claims on its box.

And then there’s the Spartus Electralife, an evolution of the Christmas Tree Vibrator invented by Leo Smith in 1950. According to the patent, the vibrator “produces an intriguing rustling sound similar to the sound of sleet falling upon packed snow.” The design didn’t quite catch on. “The Electralife is outrageously, preposterously rare—and we have two of them!” Pruitt says.

Fake winter storms to go with faux pine needles; it all begs the question of how we got here, and what level of obsession led to these inventions. The answer is a long, evolving journey that includes lots of wire, feathers, and even toilet-cleaning brushes.

Pagans decorated the solstice with evergreens, and in Europe, tree-decorating traditions can be traced to the 15th or 16th century. But the concept closest to a Christmas tree was called the paradise tree, adorned with apples for Adam and Eve’s Day on December 24, a medieval Christian holiday. By the 1700s in parts of Europe, families decorated evergreen boughs or trees with treats for Christmas. This practice was especially popular in Germany.

“The Christmas tree is a tradition that flows outward from Germany,” notes Tim Larsen, editor of The Oxford Handbook of Christmas. “German immigrants are early adopters in the United States. The 1830s see the custom notably spreading, and the illustration of Queen Victoria and her family—her husband was German—with a tree in 1848 was a key catalyst in the English-speaking world,” he explains. The Illustrated London News’ 1848 Christmas Supplement featured a drawing of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and their children around a decorated tree. The Christmas tree idea spread far and wide after that.

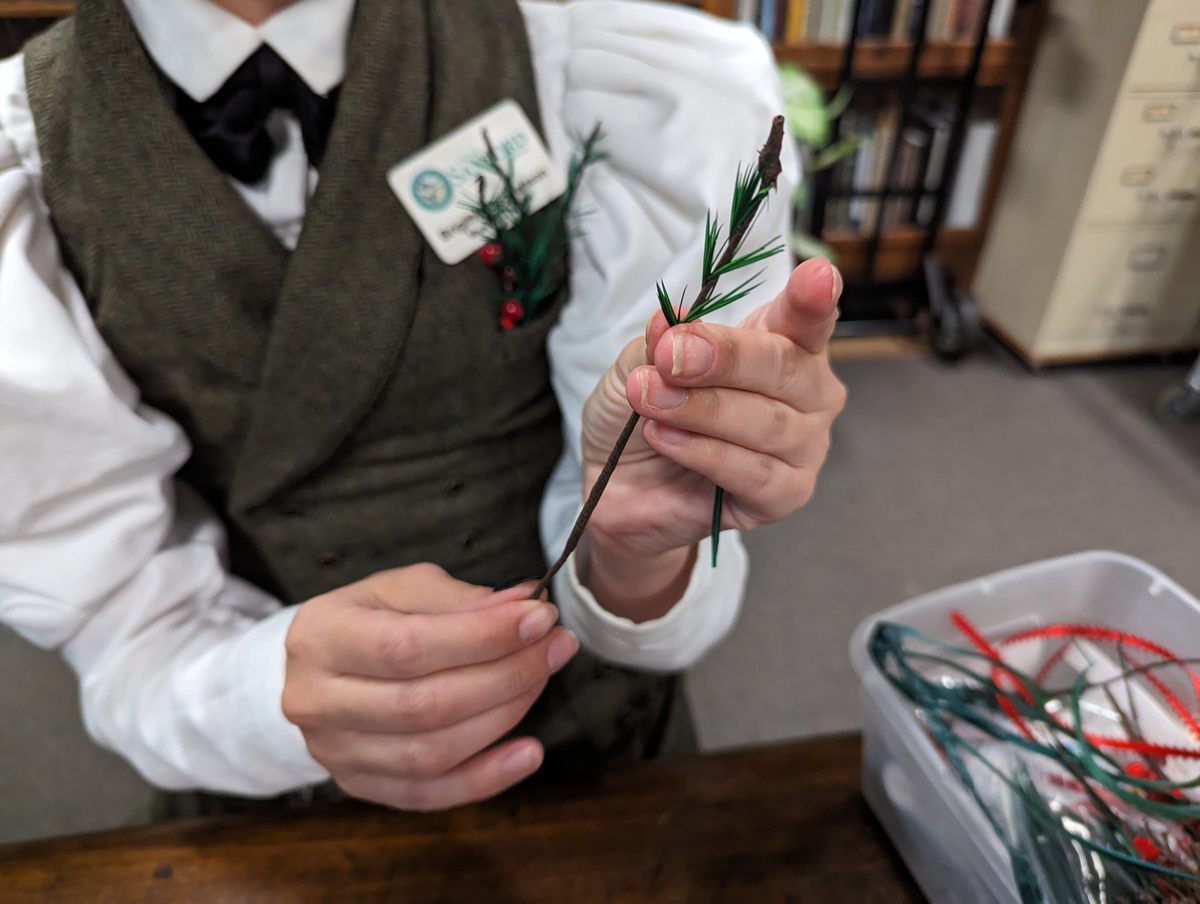

As German forests dwindled from the 1750s to the 1850s, people searched for alternative evergreen replacements that looked similar. Some folks took to crafting their own Christmas trees from wire and feathers from geese or other fowl. Feather trees still exist today, but historical creations looked nothing like modern glammed-out versions. Due to the unique way the feathers were twisted into place to form each branch’s “needles,” it’s hard to tell they’re feathers at all. Though the branches appeared sparse, these goose feather trees became a tradition, and German families emigrating to the United States brought them along.

“Feather trees are much older than you think,” notes Brigitte Stephenson, curator of the Sanford Museum in Florida, who leads an annual feather-tree crafting workshop at the museum. “Germany is a Christmas powerhouse, and Germans are the first commoditizers of Christmas. Feather trees came from a place of deforestation and a weird history of ecology.” The artificial trees were also a way to “preserve tradition so it’s not as harmful to the environment,” she says.

Americans were pretty late to the Christmas tree tradition, but caught on to the craze in the early 1800s. By the 1850s, sellers in the U.S. harvested trees wherever they could find them. Pretty soon, problems arose. By 1891, Congress passed the Forest Reserve Act to protect public woodlands. And for years, Americans wrote newspaper editorials against cutting trees down for an “absurd fad.”

While the real-versus-artificial-tree debate existed over 100 years ago, another major issue loomed: house fires. In the late-19th to early-20th centuries, lit candles often illuminated the trees. Early electric Christmas lights were also hot. Neither option was truly safe for dried-out, essentially dead trees displayed indoors.

Holiday house fires regularly made the news, so inventors devised ways to prevent them. The first artificial-tree patent went to Mary Crook in 1911 for a twisted wire tree with loops for candles or ornaments on the branch tips. While her patent sketch didn’t really look like a Christmas tree, her goal was a tree that’s “durable, inexpensive and fireproof.”

In 1917, Herman Vierlinger patented the ancestor of the modern artificial tree, calling it “strong-limbed and foldable,” as well as “handsome, glittery and brushy.” His tree also had twisted wire branches, but with “thin metal threads” poking out as pine needles. By its prickly appearance in his patent sketch, this tree was probably best handled with gloves. Nevertheless, the brush-style Christmas tree, decades ahead of its time, was born.

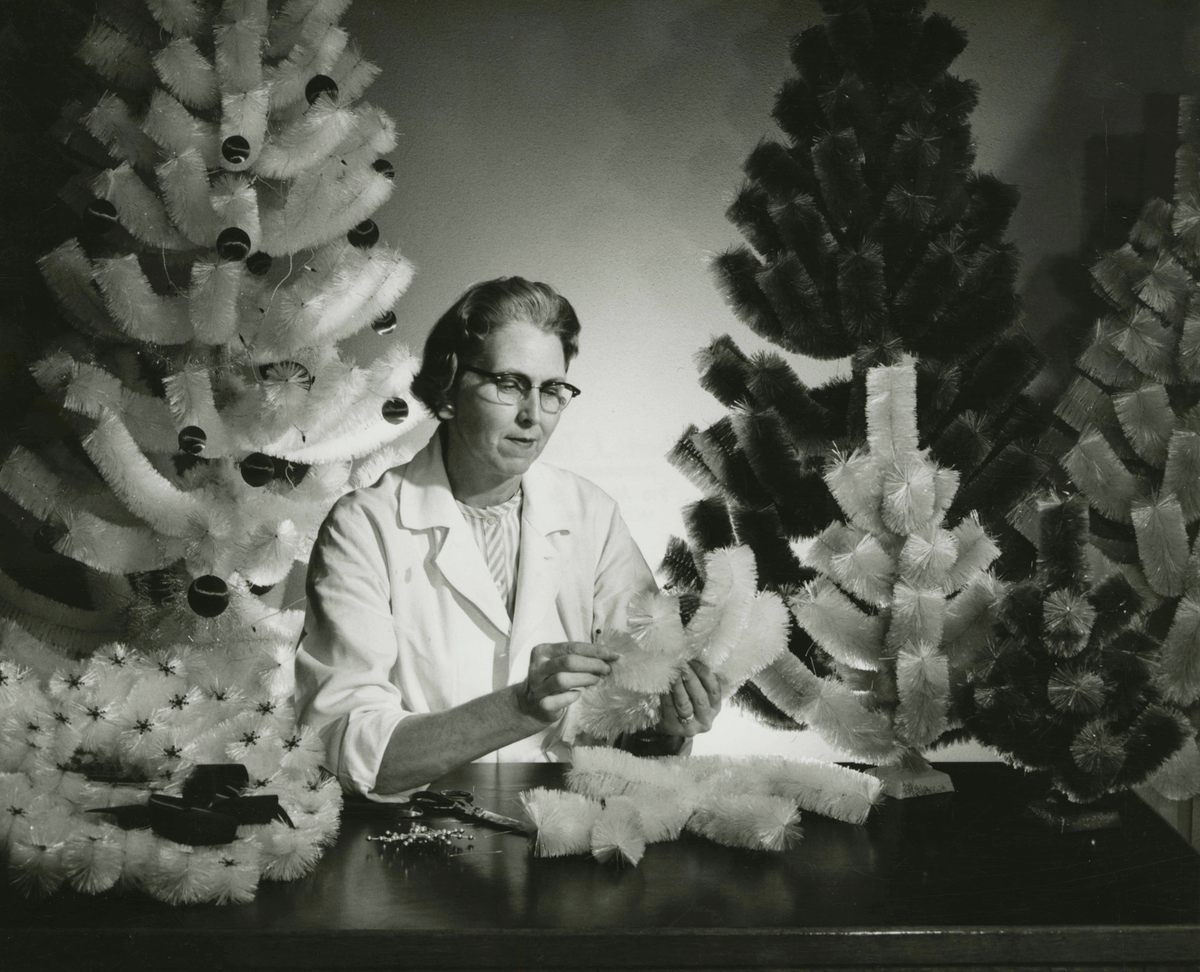

And then toilet brushes entered the picture. Many sources credit Addis, a centuries-old UK company, for coming up with bottle-brush trees inspired by tools used to clean household items like toilets. Addis is one of the first companies to manufacture toothbrushes, as early as the 1860s. In the 1940s, it made its first nylon-bristled toothbrush, and by the mid-1950s, it manufactured a variety of plastic and nylon-bristled household brushes.

However, the company distanced themselves from the toilet-brush claim in an archived letter from former owner Robin Addis, who wrote that his father purchased a company in the ‘60s or ‘70s that made artificial trees, but dumped them five years later, writing “we should never have gotten involved.”

“Unfortunately we have limited information still available,” notes current Addis director Lewis Major in an email. “We do know that Addis produced the trees applying the same technology used to produce toilet brushes, and in green to replicate the natural (pine needle) colour.”

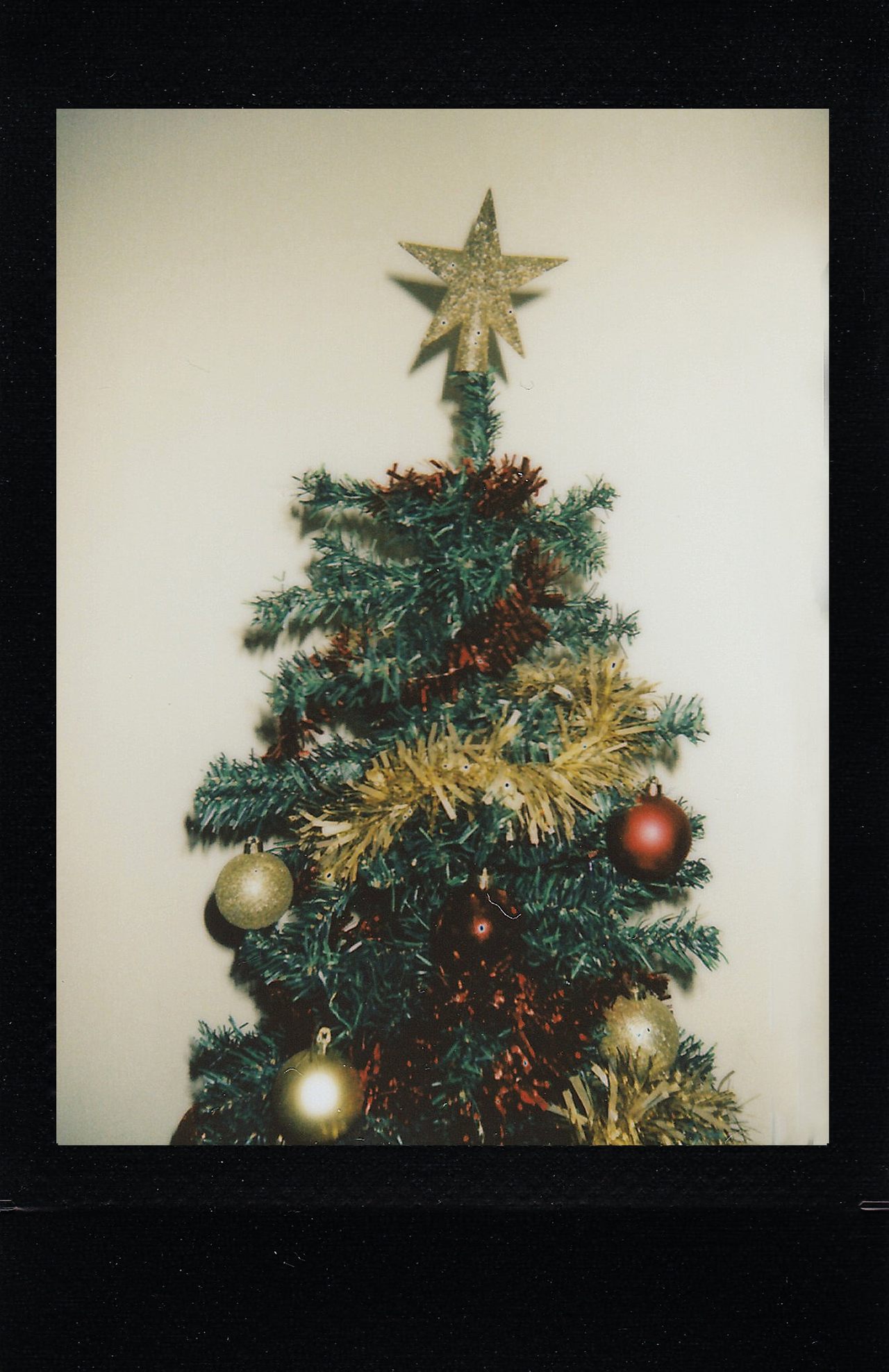

Either way, as post-war plastics took off, the bottle-brush tree trend became a hit. Small artificial trees, essentially a single cone-shaped bottle brush with a base, were a Mid-Century staple in many homes. Kitschy colors came out in aqua, pink, or white. Companies such as Plasco made a variety of quirky clear-plastic trees starting in the late 1940s, including versions that glow in the dark.

While the average 21st Century artificial tree leans towards the realistic, some companies still offer modern versions of the most unique designs. Today, you can find handmade, German-style, feather trees crafted with goose feathers, which are long, tapered, and stick out like pine needles when wrapped around the wire “branch.” There are kits to make your own feather tree as well, and Stephenson says even a four-year-old could do it. “It’s great to get your kid interested,” she says. “It’s like a magic trick.” There’s even a modernized, all-in-one version of a tree that snows, which comes pre-strung with lights, and has the option to play Christmas songs on demand.

Of course, since part of the original intention of artificial Christmas trees was to help deforestation problems, there are more sustainable versions that don’t spew out styrofoam balls. The Modern Christmas Trees’ Mod-style solution uses less plastic than standard artificial trees, thanks to its floating-disc-style structure. Plus, the company plants one tree for each tree purchased. Together, it all helps sustain a pagan tradition in a way that sustains nature as well—despite the unfortunate lack of an angel with a snowing skirt.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook