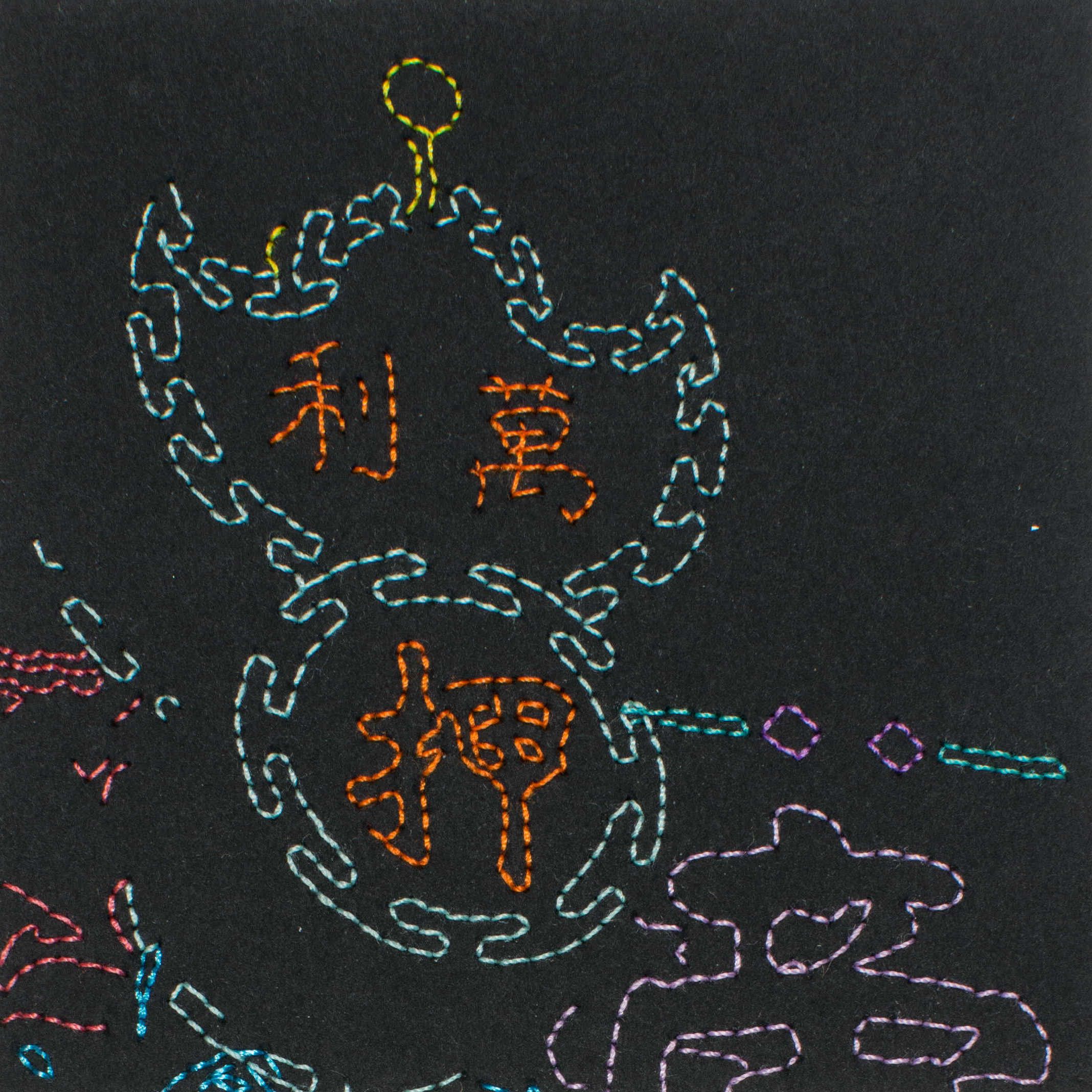

An Artist Immortalizes Hong Kong’s Neon Signs, One Stitch at a Time

Percy Lam uses embroidery to preserve an art form that’s hanging by a thread.

Hong Kong’s iconic neon signs, which for nearly a century have cast the city’s streets in a psychedelic, supercharged glow, have been rapidly vanishing in recent years. The massive signs have inspired countless artists, especially photographers seduced by this fantasia of architecture and design. But the Hong Kong-born fiber artist Percy Lam favors a more unusual and tactile approach. Since 2017, Lam has painstakingly replicated dozens of neon signs from his homeland, hand-embroidering electric lines on an intimate scale.

Each piece in Lam’s ongoing project, Millions of Neon: The Light of Hong Kong, consists of technicolor stitches marching like ants through sheets of black paper, which measure just three inches square. Lam, 28, has finished more than 100 of these palm-sized works. Each one records the name, logo, and identity of businesses from restaurants to hotels to pawn shops. He spends up to seven hours on each one.

Neon first lit up Hong Kong in the 1930s. The luminous tubes enjoyed a golden age in the region from the ’50s through the ’80s, a period when advertising adopted new formats and Hong Kong’s economy surged so quickly that it was deemed one of four “Asian Tigers.” Once markers of dynamism, tourism, and nightlife, neon signs are now widely acknowledged as cultural heritage: In 2014, the local M+museum launched an online exhibition to map and document the history of Hong Kong’s signs, which are disappearing at an estimated rate of 3,000 a year. Its curators have since crowdsourced a database of nearly 4,500 photographs.

Lam, who is currently a graduate student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, uses these images as source material. But instead of recreating them, he crops each scene so the resulting embroidery captures a fragment of a sign. The incomplete record invites closer observation of these objects, but also opens a question: How much of this history will never be described?

Atlas Obscura asked Lam about his process and dedication to this fading culture.

Why are Hong Kong’s neon signs vanishing?

A lot were built when there was no clear regulation. But as the city developed and businesses closed, signs were not being removed and maintained, so the government started to get concerned about safety. Those signs are big and heavy. Now, the government annually examines existing signage. If they don’t pass certain requirements, they get removed.

Another reason is that technology has developed. LED signs are cheaper and last longer. They are also easy to maintain and can provide more range of colors.

What motivates you to replicate these signs?

Firstly, aesthetics. I previously used Pez candy and wrappers to build a Hong Kong cityscape. The colors and form reminded me of the architecture, then I began associating it with its neon culture. I thought I could replicate the signage using the wrappers, but I saw more of a similarity between the quality of thread and the light.

Secondly, nostalgia. I think about memories and my love of Hong Kong. I moved to Hawaiʻi when I was 17, so it was challenging to fit into U.S. culture. Even though I am a U.S. citizen, I don’t really feel like my self is American. But I also feel a difficulty to connect to Hong Kong. So all my projects are a re-finding of identity—of who I feel I am.

Stitching is such a time-consuming act. Why did you choose this particular medium for this project?

I feel like this not only celebrates the craft of hand embroidery but also the work of neon craftsmen. The lines can be seen as a mending, too, of the connection between myself and Hong Kong.

Have you seen any of these specific signs in person?

Not that I can remember. I don’t go to Hong Kong frequently, but when I visited last summer, I took some photographs of signs. I also contacted a local neon master because I wanted to learn how to bend Chinese characters. He told me stories of how the neon industry is dying: Now there are only seven active neon workshops left. That means that they don’t have projects all the time, but they are willing to do the work. He was pretty young—in his 40s—but a lot of workers are very old and will soon retire.

Are there ongoing efforts to save this very particular visual culture of Hong Kong?

I’ve been following a Hong Kong group on Facebook that keeps track of the removal of signs. They ask people to notify them if they know a sign is getting taken down, so they can go there to create a final documentation of it. M+ has also saved some classic signage, but they can’t do it all, of course.

How do you hope to eventually display the series?

My initial idea was to make a quilt. But while I want to present the pieces as an object, I also imagine laying them on a long table, like specimens. Then people can walk around, sit down, and examine them. I want to provide a space for an audience to take a closer look, because I see this as an act of preservation. I’m creating an archive of a dying culture.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook