The Delicate Art of Identifying Bats By Their Penis Bones

They’re roughly the size of a hyphen—which makes them extremely easy to lose.

On many days, when her lab is open, Stefanía Briones’s workstation is padded with paper towels stained with swirls of purple and blue. It looks a little like a madcap tie-dye experiment, but she is actually poking around for the bones inside bat penises. It’s a tricky task, because the bats Briones works with tend to be pretty small—just a few inches long—which means that their penises are even smaller. The bones inside them are often just millimeters long, roughly the length of a hyphen. As a research affiliate in the mammals department of the Field Museum in Chicago, Briones has become a savvy bat-penis-bone sleuth, cleaning and preparing upwards of 100 of them in the name of science.

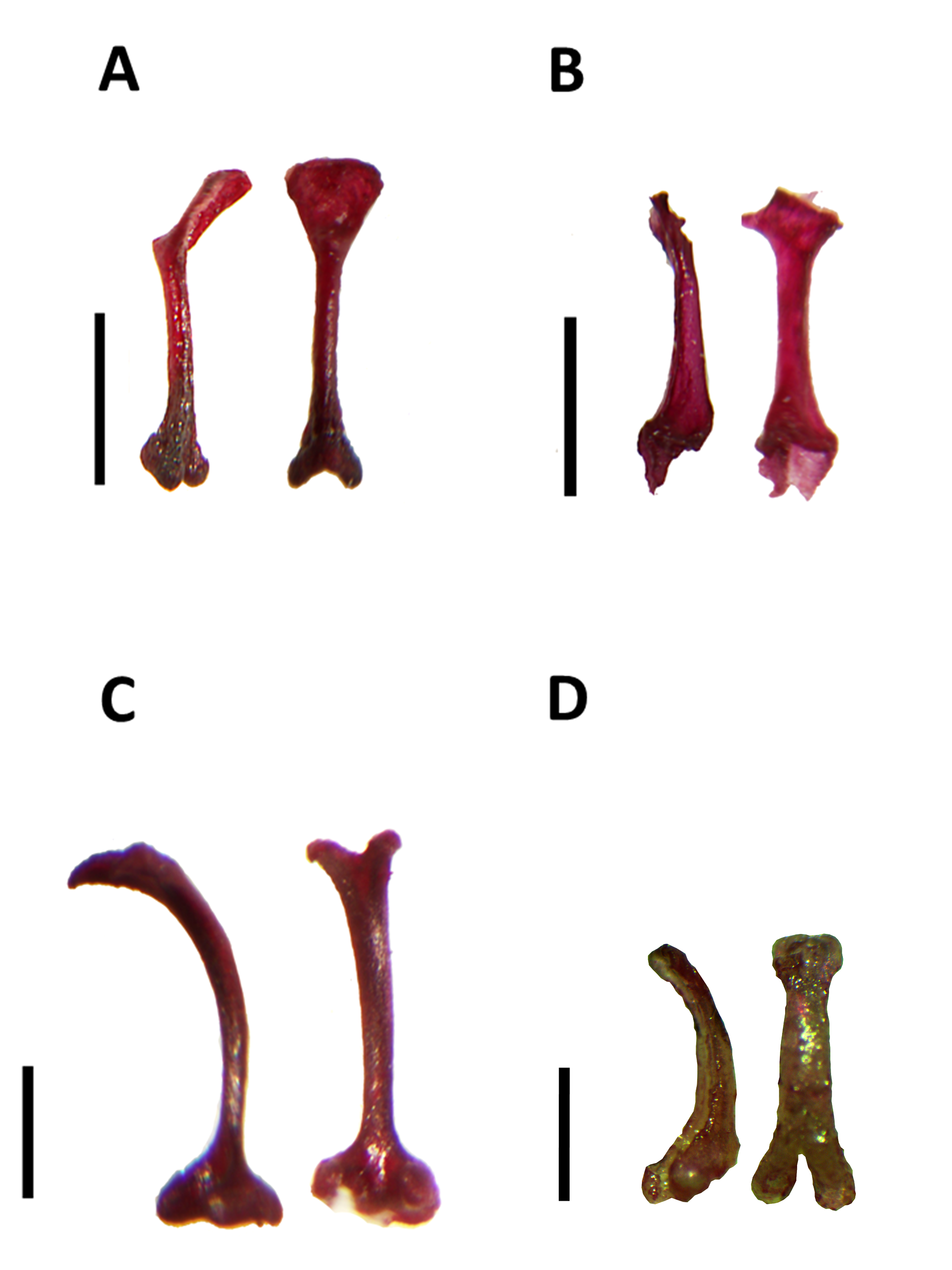

Many mammals have a penis bone, also known as a baculum—they’re found in some primates, rodents, insectivores, carnivores, and bats—and many of those bones have distinctive shapes. Researchers from the University of Eswatini, Maasai Mara University, and the Field Museum recently recorded several new genera of vesper bats, as well as three new species found in Kenya and Uganda. Along with genetic data, information gleaned from studying teeth and skulls, and the calls the bats emit while echolocating their way through the night, the penis bones helped them do it.

Some bat bacula look like itty-bitty arrows, while others have generous curves; some are flat at one end while others, from the genus Rhinolophus, appear to swoop into two little lobes, like a cartoon heart. (“It’s super cute,” Briones says.) Across vesper bats, a family that includes hundreds of species, bacula “are as different as night and day,” said Bruce Patterson, a curator of mammals at the Field Museum, and senior author on the team’s paper forthcoming in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, in a museum release.

Researchers have been studying bat bacula since at least the 1880s, according to an article in a 1949 edition of the Journal of Mammology, which recounted “increasing interest” in penis bones as classification tools. To access a baculum, Briones first snips the penis off a preserved specimen with extremely dainty clippers. She soaks the penis in water overnight to wash off excess alcohol. Then, she has to get to the bone.

The Field Museum houses a hungry colony of dermestid beetles, which other departments enlist to help strip the flesh from their specimens, but a baculum is way too small for that. “We would totally lose it if we put it in the dermestid colony,” Briones says. Instead, she puts the penis in a potassium hydroxide solution and adds some colorful dye that stains the bone and (ideally) makes it easier to see. She pops it in a heated incubator for several hours, hoping that the solution will dissolve the flesh. Then she dumps the solution out onto her paper towels and hunts for the bone.

Occasionally, it’s easy. “Sometimes, the tissue will melt completely and I dump it out and the bone is right there,” she says. Other times, she’s left with a “glob” of tissue and needs to scrape away at it to find the bone beneath. “It’s like when you eat chicken wings and there’s a little meat left on the bone,” she adds. “Sometimes it looks kinda stringy.”

Once the bacula are cleaned, they can easily (and accidentally) migrate across the table if a scientist reaches for a tool, like little dust grains lofted in a gust of wind. “I sometimes feel like they have a life of their own, because they just jump,” Briones says. “Even if you breathe on it, it will move.”

Working with extremely tiny specimens often involves MacGyvering surprising protocols. Lisa Gonzalez, an assistant collections manager of entomology at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles who works on an ongoing survey of the city’s resident insects, sometimes repositions her tiniest specimens—ones even teensier than a grain of rice—using a single-bristled brush. Briones wields a dental tool—the sharp, hooked instrument that a dentist might use to poke a cavity—to gently nudge the bone into a gel capsule. It’s roughly the size of a multivitamin.

Briones has found that successfully wrangling the tiny specimens requires a careful protocol, a perimeter around her work station, and a slightly fanatical degree of organization. She arranges her tools the way a surgeon might arrange scalpels, so she can reach for them in order and never finds herself scrambling for what she needs (which could swipe the bacula off the table in the process). Then, she dives in with confidence and an unflappably steady hand. Briones cultivated hers by applying makeup on Chicago’s Brown Line trains. Once you’ve mastered cosmetic choreography in the herky-jerky commotion of a rush-hour train, a bat penis (even a very, very tiny one) is no sweat, Briones jokes. “Liquid eyeliner on the ‘L’, that’s the graduation test.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook