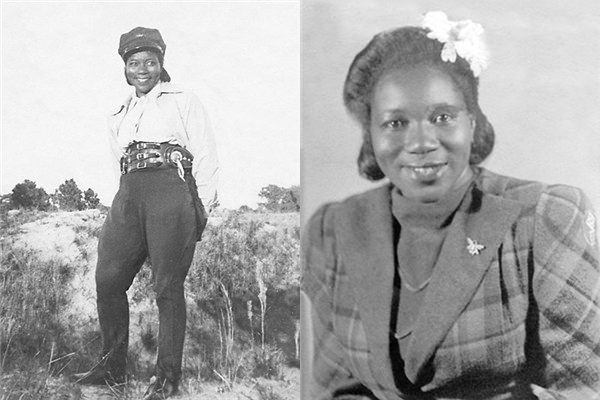

Bessie Stringfield, the Black Motorcycle Queen of the 1930s

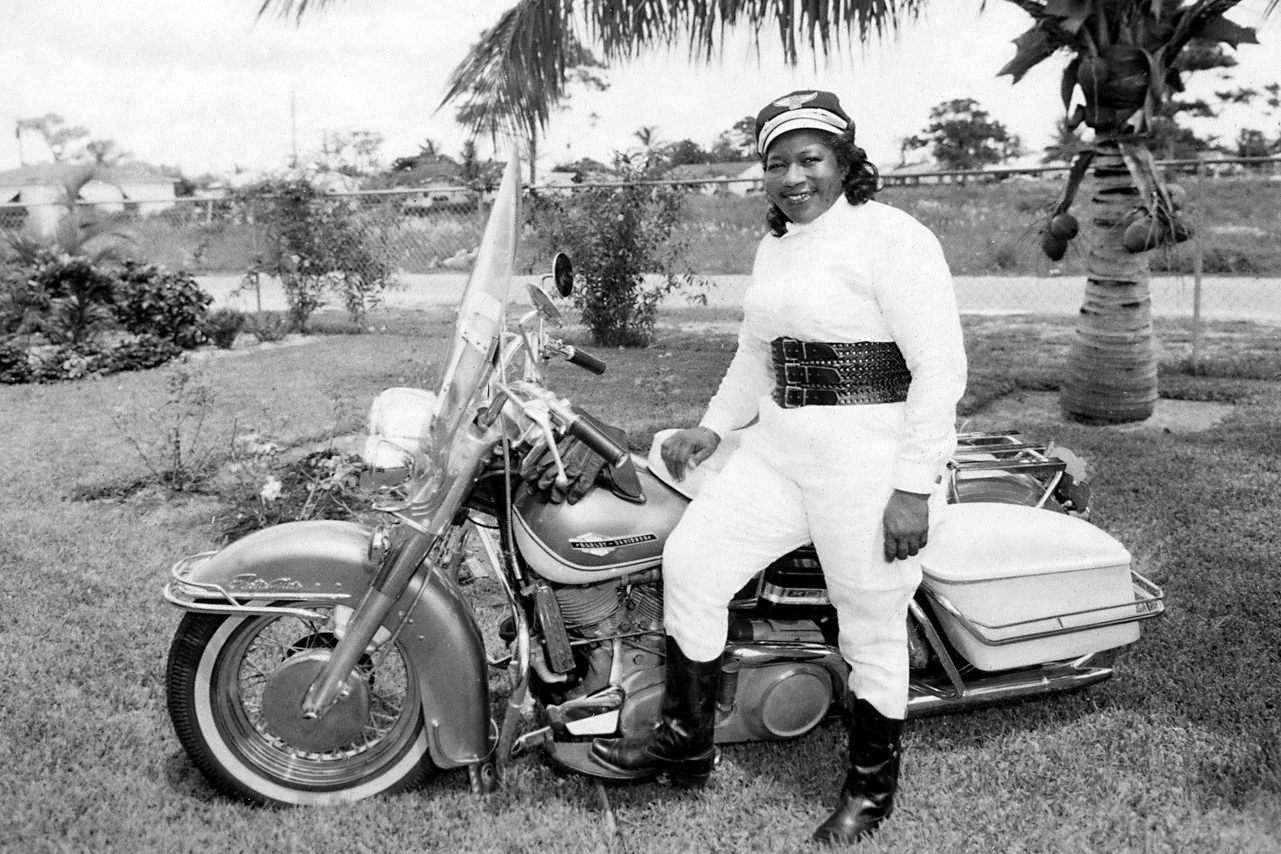

She owned 27 Harleys and rode them all over the United States, before settling in Miami.

In the 1930s, Bessie Stringfield practically disappeared in a cloud of smoke, bolting across the walls of a wooden, bowl-shaped arena: the Wall of Death. She was on her way across the country, traveling completely alone—again—on a Harley. Bessie Stringfield, an African-American Bostonian originally from Jamaica, had already earned a title that would be given to her years later: “The Motorcycle Queen.” From 1929 until her death in 1993, she rode her motorcycle around the Americas, defying several stereotypes about what Black women could do.

At first, riding a motorcycle across the country might seem on the low end of remarkable acts, but in the 1930s, especially for a Black woman, that was not so. Stringfield rode across the country on a motorcycle only 10 years after women gained the right to vote. And the roads were not the smooth, friendly lifelines that snake across the country today; Stringfield traveled before many roads were paved—the American interstate highway system wouldn’t even be proposed until 1956. If she was traveling through Arkansas in the middle of the day and broke down? Stringfield had to be her own mechanic.

As Stringfield told her protege and biographer Ann Ferrar, no matter where she traveled, ”the people were overwhelmed to see a Negro woman riding a motorcycle.” Black people were not welcome in almost any motel across the country, so she often stayed with Black families she met along the way or slept on her bike at gas stations under the night sky.

Bessie Stringfield began traveling young. She was born in 1911 as Betsy Ellis, and her family immigrated to Boston, Massachusetts, when she was a young child. From the start, Stringfield was faced with difficulties in life, though the exact details of her parents and some of her upbringing are muddy. Some sources say her mother was a domestic worker named Maria Ellis, her father was Maria’s employer, James Ferguson, and both died of smallpox soon after arriving in the United States. Other sources, such as an interview with Stringfield by Bea Hines in the Miami Herald in 1981, say her mother died in childbirth—this detail is added to by Ferrar, who interviewed Stringfield for years, saying that after her birth mother died, her father, “a biracial West Indian, took her to New England but then abandoned her at age five.”*

In any case, Stringfield grew up in Boston, and when she was orphaned at age five she was adopted by a wealthy Irish woman who was never named in interviews. Eventually, her name changed to Bessie. According to the 1981 interview in the Miami Herald, her mother was protective, and didn’t buy her a motorcycle straight away; the first bike she learned to ride was that of a neighbor who lived upstairs. (And, because she’s amazing, she taught herself how—not a user-friendly experience in the 1920s.) “My mama had a fit. Nice girls didn’t go around riding motorcycles in those days,” Stringfield said to the Miami Herald. But, on her 16th birthday, her adoptive mother’s worries lost out. Stringfield said her mother “gave me whatever I wanted,” according to Ferrar’s book Hear Me Roar. And she wanted a motorcycle.

Stringfield immediately took good care of a serious case of wanderlust. After flipping a coin onto a map of the United States, she would pick the random location as a destination and make the trip. From 1925 through 1929, she made several trips in and out of Boston, getting a taste for the road. Over the next few years, she became the first Black woman to ride a motorcycle in every one of the lower 48 states and made motorcycle trips to Brazil, Haiti, and parts of Europe. While her first bike was an Indian Scout model, Stringfield soon discovered that she loved Harleys, which became her bike of choice; she owned 27 in her lifetime.

Stringfield didn’t stop after the first trip. She rode alone eight times through the 1940s. To earn a living as she traveled, Stringfield wowed crowds at fairs and carnival sideshows with stunt acts including the Wall of Death, in which motorcyclists zoom sideways along the walls of a wooden, bowl-shaped arena and glide nearly (or actually) upside-down in spherical cages. Stringfield also competed for coveted monetary prizes in flat-track races, where motorcyclists race over dirt oval tracks. Though she entered races disguised as a man, she was often denied the prize money after it was revealed that a woman beat the men.

Shelly Connor writes in First-Wave Feminist Struggles in Black Motorcycle Clubs that Stringfield was one of few but visible women who were motorcyclists before the reactionary 1950s version of femininity took hold. Connor writes that some early Black motorcycle clubs included both male and female members in the 1930s, but it was still unusual for women to gain notoriety. Black female motorcyclists in particular “knowingly enter a space that brings with it (in many cases) the continuance of racialized, sexualized, patriarchal hegemony that they face at work and home,” Connor adds. Stringfield was at the nexus of it all.

Racism was a danger that followed Stringfield everywhere, often landing her in precarious situations. As Stringfield said to the Herald in 1981, “Colored people couldn’t stop at hotels or motels back then. But it never bothered me”—a remarkable attitude considering that lynching was still common and legal in most towns in 1930s America, and desegregation laws were decades away. Riding alone on uncertain roads across the segregated United States was dangerous. Stringfield was knocked off her motorcycle by a white man in a pickup truck, but attributed the violence in interviews to mere “ups and downs,” often citing her Catholic faith and upbringing as a source of both her luck and her skill, according to Ferrar.

Despite being a civilian woman, Stringfield became an asset to the United States government during World War II, as a motorcycle dispatcher. Amid her travels, Stringfield made it through the deaths of three children and six marriages, which all ended in divorce. (She taught two of her husbands, by the way, how to ride; Stringfield was the name of her third husband, who asked her to keep his name because he was sure she’d become famous.)

Stringfield was keenly aware of what she defied in the eyes of others, prided herself in doing her hair and makeup everyday, seemingly stealing men’s hearts by the dozen with her powerful personality. Hines’s piece in the Miami Herald shows this best, when Stringfield, then 70 years old, says “with a mischievous look in her eyes”: “All my husbands, except one, was from 22 to 24 years my junior. Wouldn’t have a man over 35, even now.” She laughs at her own remarks. “Shucks, you’re not writing that, are you honey?”

After her mother in Boston passed away in 1939, Stringfield moved to Miami permanently, where she eventually bought a house and became a registered nurse. In Florida she faced discrimination from police for continuing to ride her motorcycle, she told Hines, but thwarted some of the officers by impressing the motorcycle police captain with her skills, performing figure eights and various tricks. “From that day on, I didn’t have any trouble from the police, and I got my license too,” Stringfield said. By then people close to her called her BB, but publicly she was known as the “The Motorcycle Queen of Miami” and formed the Iron Horse Motorcycle Club, which no longer exists today.

Stringfield passed away at age 82 in 1993 from complications related to an “enlarged heart,” but in October of 1981, Stringfield was “going strong,” and working as a nurse, according to the Miami Herald. At age 70, she was still riding around Miami and riding her motorcycle to church, impressing every person in her path. In the year 2000, the American Motorcycle Association honored her by creating the Bessie Stringfield Award, and Stringfield was added to the Motorcycle Hall of Fame in 2002. Stringfield also inspired a series of graphic novels in 2016, aimed at children, spreading the inspiration of her life to a new generation.

Looking back on her life, Stringfield said to the Miami Herald, during another 1981 interview with Hines, with a twinkle in her eye: “Yep. I never was like anybody else.” But Stringfield did more than just go against the grain—she unapologetically and publicly shocked her observers out of their comfort zones, blowing stereotypes off the road for many generations of women to come.

*Update: The story has been updated to include details of Stringfield’s early life contributed by Ann Ferrar.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook