In the Canary Islands, a Mysterious Phantom Isle Haunts Local Imagination

The legend of San Borondón all started with an Irish saint.

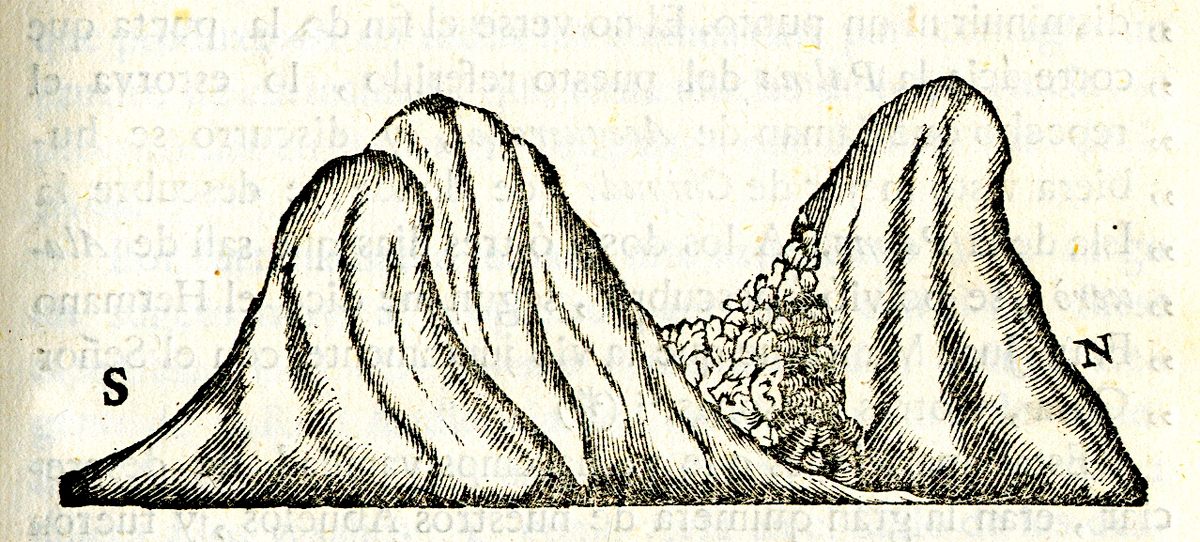

One September evening in 1957, the photographer Manuel Rodríguez Quintero was wandering the western hillsides of La Palma, in Spain’s Canary Islands, when he spotted a shape out in the Atlantic. The outline appeared crystal clear, silhouetted against the setting sun: a craggy island rising into twin mountain peaks. Stunned, Quintero raised his camera and clicked the shutter.

Quintero’s photograph soon topped a double-page spread in the Spanish press. He had captured on film the object of a centuries-old quest: the mythical island of San Borondón.

The Canarian philologist Marcos Martínez Hernández, at the Complutense University of Madrid, has described sanborondonismo as “one of the most defining features of Canarian culture since the 16th century.” The phantom island is ubiquitous in the archipelago’s art and literature—a symbol of longing for an elusive utopia, tinged with fear that one day, the real volcanic islands that make up the Canaries might also disappear.

The myth of the elusive island all started with an Irish saint.

In the sixth century, the legend goes, Saint Brendan set sail into the Atlantic, in search of the biblical utopia known as the Promised Land. His crew of clerics voyaged for seven years, caught in a loop of enchanted islands that repeated, year after year. Early in the voyage, they landed on one and began to prepare a mass when they felt it move under their feet. They fled to their boats just in time to see the island submerge and realized they had been standing on a giant whale. This wandering whale “island” became part of their strange circuit, reemerging every year for them to celebrate Easter on its back.

The tale was doubtlessly elaborated over centuries—as the real journeys of Saint Brendan were embellished with fantasy and fused with mythical characters. A millennium after Brendan’s voyage, the legend of his maritime explorations gained further popularity, as Columbus’ arrival in the Americas marked a new era of Atlantic discovery.

“The seas filled with discoverers, adventurers, pirates, travelers, merchants, who tried to discover new lands,” says Luis Regueira Benítez, archivist at the Canarian Museum on Gran Canaria.

These European “discoveries” included the Canary Islands, which the Spanish colonized from the islands’ Indigenous inhabitants in the late 15th century. Located at the start of the transatlantic trade winds, the archipelago soon became a hub for European colonial adventurers. Their wanderlust met with a peculiar local phenomenon.

“There’s an optical effect in the atmosphere that makes you see an island when really there’s nothing there,” Regueira explains. Scientists remain uncertain about what causes this illusion. They also aren’t sure how Quintero’s photograph captured the craggy outline of Saint Brendan’s Island (another name for San Borondón) in 1957. Nevertheless, in the 16th century, sightings were so frequent that the island appears on several maps, generally located west of La Palma—the westernmost island of the archipelago.

Fascinated by these maps, Regueira partnered with fellow archivist Manuel Poggio Capote to delve deeper into the legend, eventually publishing their research in the book La Isla Perdida (“The Lost Island”). They found numerous accounts of voyages to find the mysterious island, launched from the Canaries by everyone from private sailors to government-chartered expeditions.

“Boats even went out when the island was seen, but arrived to find it wasn’t there,” Regueira says. These perplexed explorers associated the vanishing island with Saint Brendan’s whale—giving it the Spanish epithet San Borondón.

By the 18th century, a famine in the Canary Islands had brought new urgency to these persistent tales of undiscovered nearby land, recalling Saint Brendan’s quest to find the biblical utopia.

“Finding San Borondón was like finding a granary, a storehouse to quell the famine and hardships that existed in the Canaries as a result of drought and plague,” says José Gregorio González, host of the radio show Crónicas de San Borondón and author of several books on Canarian mythology. “It was [seen as] a promised land where the earth was very fertile, where fruits grew spontaneously, with lots of abundance.”

While this desperation motivated several more expeditions to find Saint Brendan’s Island, the legend also had a darker side in popular culture. “There was a belief that one of the [visible] islands on the surface would sink, and San Borondón would emerge,” González says. “That could be linked to fear of volcanoes, of catastrophe.”

Canarians clung to these superstitions until the 19th century, when the dawn of scientific rationalism produced theories about the optical illusion that produced the vanishing island. In La Isla Perdida, Poggio and Regueira list the seven most plausible theories, ranging from a refractive effect that magnifies distant objects on the horizon, to a shadow or reflection of an existing island, like the twin volcanic peaks of La Palma. They believe San Borondón may be all of these things at different times, feeding off the imagination of those who look for it.

But these explanations have not loosened San Borondón’s grip on Canarian culture. The nonexistent isle is everywhere. It gives its name to businesses, farms, streets, and villages. It’s the subject of poems, songs, and countless artworks—including murals that cover whole buildings. Most Canarians know of San Borondón from childhood, through school activities, picture books, or grandparents’ tales.

“As children, we knew the island didn’t physically exist, but in a way we all believed in it,” González says. “It formed part of our imagination, our dreams, our language.”

In 2005, photographers David Olivera and Tarek Ode decided to test how much Canarians still believe in San Borondón. Following a secretive, year-long collaboration with artists across the archipelago, they announced an exhibition called La Isla Descubierta (“The Discovered Island”). It featured the diaries, photographs, and drawings of a fictional 19th-century botanist, depicting the landscapes, flora, and fauna of San Borondón.

“Our intention was to bring something new to the legend,” Olivera says. “We presented it as if we had discovered a historical archive.” The fiction was more successful than even they had hoped. “Some media believed it, published it, and later they called, scolding us, asking why we had lied.”

Some enthusiasts still speculate that Saint Brendan’s Island once really existed, but sunk beneath the waves. Although always a marginal theory, the idea has a haunting resonance in an archipelago whose topology is periodically transformed by volcanic activity. La Palma was brutally reminded of this in December 2021, when the Cumbre Vieja volcano erupted, spewing lava down its western flank. Today, the banana groves and whitewashed villages where Quintero snapped his famous photograph in 1957 are torn through by a black tongue of volcanic rubble, which extends into the Atlantic as a newborn peninsula. Some geologists have even suggested that a catastrophic future eruption could cause a huge chunk of La Palma to collapse into the sea. In the Canaries, solid land is not always so solid.

Tongue-in-cheek references to this threat have slipped into San Borondón’s modern depiction. El Volcán, a 1980s Canarian children’s TV show, features a talking puppet volcano, who accompanies three children to find San Borondón. The theme song trills, “The volcano, the volcano, he only wanted to play.”

In La Non-Trubada, a short film by Alejandro Artiles Rodríguez, media coverage of the La Palma eruption is interrupted by the sudden emergence of San Borondón, which rapidly becomes a new tourist hotspot. “I wanted to critique how every time something new happens, the focus of attention changes,” he explains.

Artiles’ short film also alludes to a threat more pressing to many Canarians than volcanoes: the cultural annihilation of mass tourism. As the islands’ rocky outcrops and black sand beaches disappear under high-rise hotels, San Borondón has become a bastion of Canarian identity, invoked by everyone from folk music groups to traditional craftsmen. “San Borondón is the refuge where Canarians can believe our marvelous islands still exist,” Olivera says.

For some, it also inspires an alternative kind of tourism. “There’s a space for legends in conscious tourism, quality tourism that brings real richness,” González says. In this spirit, Poggio and Regueira hope to open a San Borondón museum, using the mythical island to explore the archipelago’s history.

In the arid canyons of south Tenerife, ecologist Diego Rodríguez runs San Borondón Organic Farm, where volunteers are building a sustainable community, inspired by the islands’ historic utopian quest. “Returning to traditions, to connection with the planet, to harmony with living beings, is reunion with that paradise of San Borondón,” he says.

The legend of San Borondón endures because it has always reflected the islands’ own shifting preoccupations. Today, Canarians no longer yearn for elsewhere, but to preserve what was here all along.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook