The First (Documented) Black Woman to Serve in the U.S. Army

Cathay Williams, who posed as a man in order to enlist in 1866, leaves a legacy that’s open to interpretation.

In the spring of 1865, Cathay Williams, like many other freed slaves, found herself without a job.

During the American Civil War, Williams had worked as a cook and washer for the anti-slavery Union side, making hundreds of meals for General Philip Sheridan’s tired troops on the battlefields and scrubbing their dirty dishes.

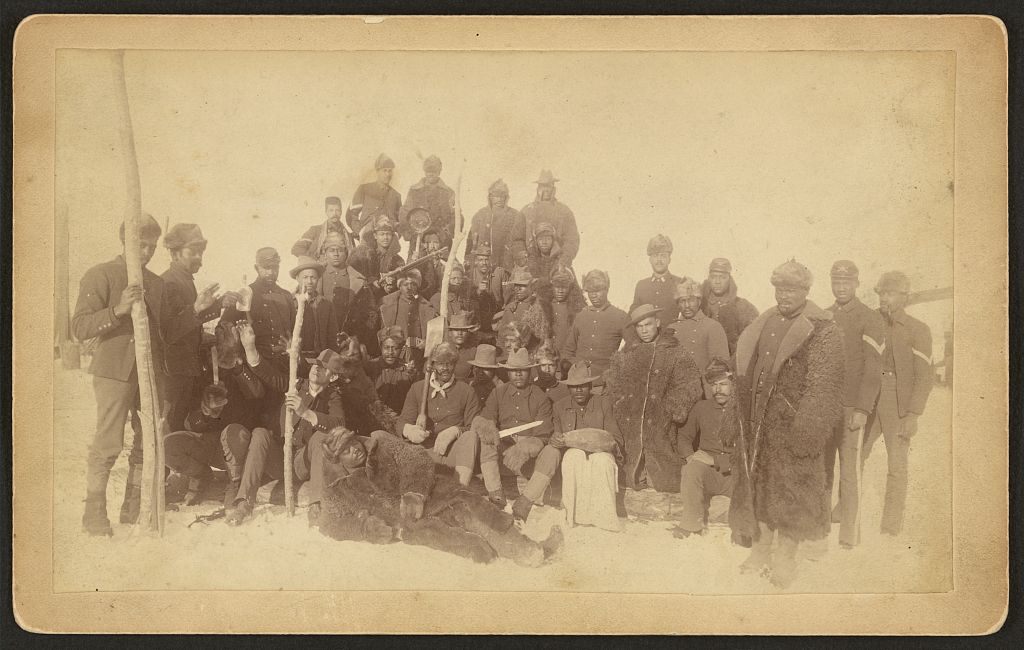

Her experience behind enemy lines possibly informed her undercover aspirations, and provided solid intel for her years incognito as the only documented female Buffalo Soldier, the first African-American peacetime army regiment after the Civil War (and an inspiration for Bob Marley’s song of the same name).

According to some historians, Williams was a trailblazer who deserves praise equal to many great black pioneers. However, others argue there isn’t enough evidence to show she’s worthy of this distinction. There is scant documentation of black women from the era who may have achieved greater feats, making it impossible to assess Williams’ true place in history.

Born to a freeman in 1844, Williams grew up in Independence, Missouri, but she was far from independent. Her mother was a slave, and according to arbitrary codes, she inherited that status, becoming a house slave for William Johnson, a rich farmer. Age 17 marked one of many turning points for Williams and for the divided country. Johnson died in Jefferson City during the onset of the Civil War, but his death did not release her from bondage.

Around 1861, the 13th Army Corps Union soldiers in Jefferson City took Williams, other slaves, and freed persons to Little Rock, Arkansas, under Colonel William P. Benton’s command. “I did not want to go,” she said in an interview with the St. Louis Daily Times in 1876. Colonel Benton told her she’d cook for the Union soldiers, but there was one slight issue. She “had always been a house girl and did not know how to cook.” She learned quickly.

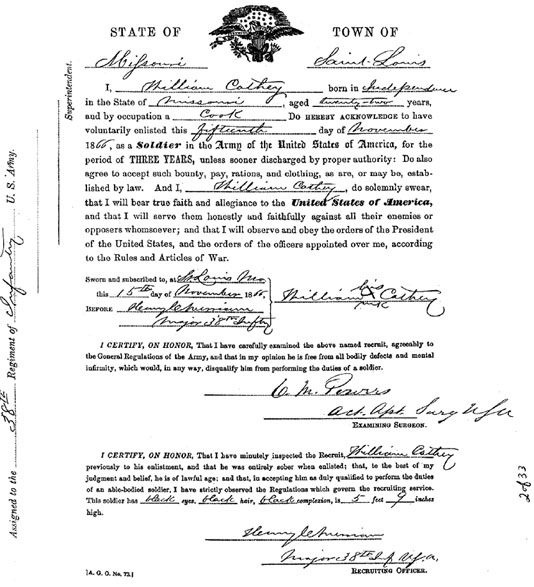

After the war’s end, she returned west to Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, but little is known about what she did, until one recorded moment. On November 15, 1866, Cathay Williams—under the inscrutable, male alias William Cathey—enlisted in the 39th United States Infantry Company A under Captain Charles E. Clarke in St. Louis, Missouri. This infantry, along with six others, became the Buffalo Soldiers.

Women weren’t allowed to serve in the army, but plenty did anyway. Under the guise of Franklin Flint Thompson, Sarah Emma Edmonds served in the Michigan’s 2nd Infantry. Jennie Hodgers, known as Albert Cashier, fought in over 40 skirmishes for the 95th Illinois Infantry. Frances Clayton, Mary Galloway, and the Confederate spy Loreta Janeta Velazquez are a few Civil War examples on a long, known list of women from Joan of Arc to Hua Mulan.

These women’s reasons for enlisting varied. Sarah Emma Edmonds wanted to serve her country and assert her independence. In 1865, she once wrote in her memoir, “I could only thank God that I was free and could go forward and work, and I was not obliged to stay at home and weep.” Others, like Florena Budwin, wanted to fight alongside their husbands, and many from working class or poor backgrounds needed an income.

The latter was one of two reasons Williams enlisted. The military was (and still) provided freed black men job security, money, and a way out of poverty when prospects were little to none. It was even harder for black women. “I wanted to make my own living and not be dependent on relations or friends,” Williams said. A steady paycheck assured her the independence she wanted, but her cousin was another reason she joined. Her cousin’s name is unknown, but he and his friend knew Williams’s secret. “They never ‘blowed’ on me,” she told the St. Louis Daily Times.

How they kept it for so long and from 75 other privates remains conjecture. Buffalo Soldier historian Frank Schubert says “this illuminates an incompetence in the medical staff. If the guy [doctor] had done his job, she wouldn’t have been in the army.” During the Civil War, there was such high demand for soldiers that some infantries took anyone that looked somewhat healthy and down to fight. With so many soldiers on the battleground, women could take cover in plain sight because no one was looking. U.S. National Archivist DeAnne Blanton adds, “because black people were invisible as far as individuals and being paid close attention to, we know [of] hardly any black women who passed as men in the army.”

Despite Williams’s army knowledge, guarding the expanding Western frontier from Native Americans, cattle thieves, and outlaws was extremely intense. She got sick quite often. Starting in February 1867, she was hospitalized for an unknown illness and on April 10 for an itch, which by 1800s medical standards “was usually scabies, eczema, lice…”

When she was healthy, she marched through Kansas and New Mexico from fort to fort. “I carried my musket and did guard and other duties while in the army,” she said in the St. Louis Daily Times interview. There are no historical records to confirm she fought enemies or fought in combat, but she did her job, until she couldn’t do it anymore.

In January 1868, after eight months off sick leave, her health declined. She was admitted to four hospitals on five different occasions, and no one ever figured she was a woman. Even if she abstained from undressing, there are no records of her treatment. For many historians this leaves more questions than answers. In the 1992 article “Black Woman Soldier 1866-1868,” Blanton wrote that it “raises questions about the quality of medical care, even by mid-19th century standards, available to the soldiers of the U.S. Army, or at least to the African-American soldiers.”

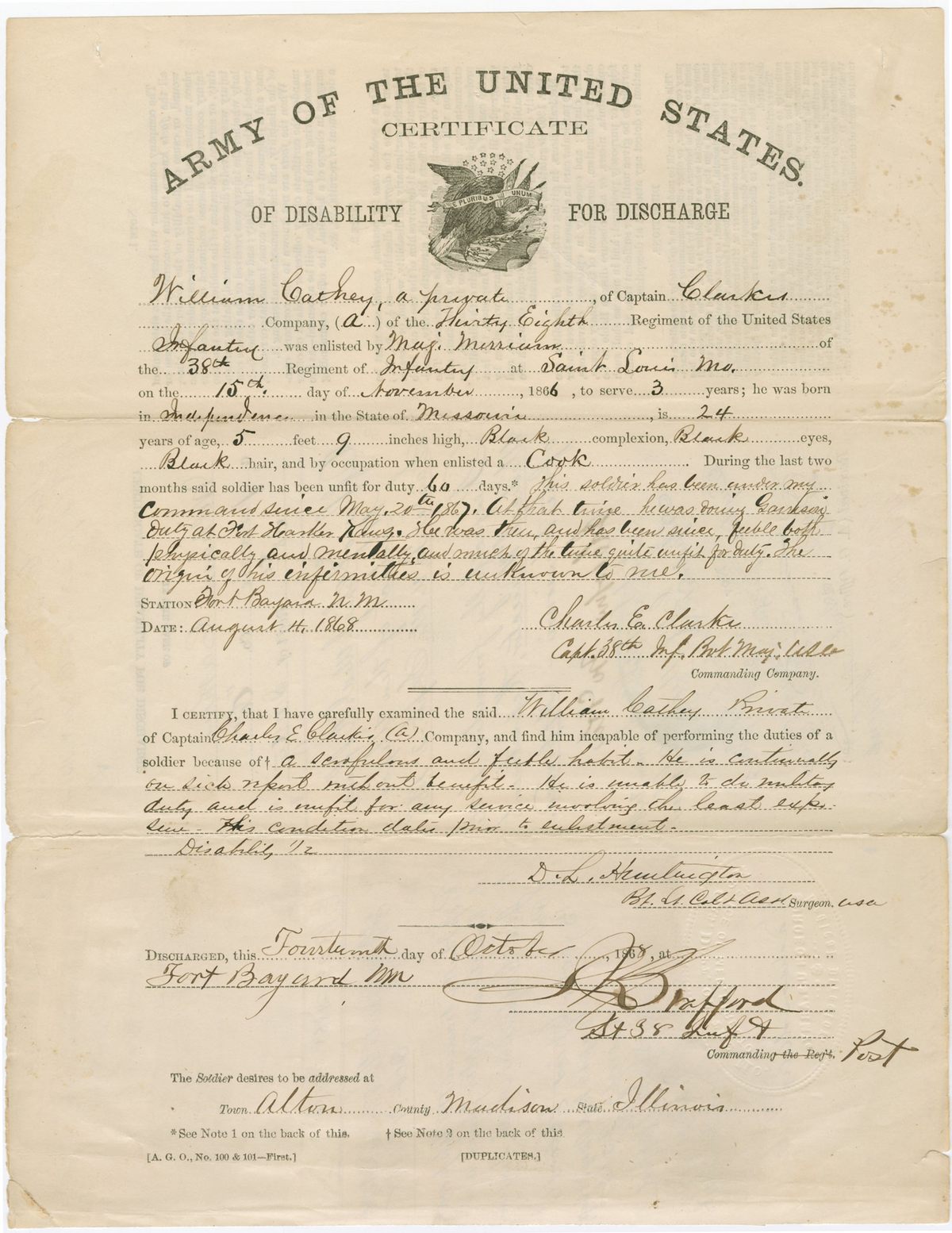

Eventually, a post surgeon discovered William Cathey was really Cathay Williams. From January 1868 up to that point, Williams was already fed up with the army. “Finally I got tired and wanted to get off. I played sick, complained of pains in my side, and rheumatism in my knees.” In her discharge disability certificate, the surgeon claimed William was “continually on sick report without benefit. He is unable to do military duty.... This condition dates prior to enlistment.”

So, on October 14, 1868, William Cathey was discharged from the 38th infantry at Fort Bayard, New Mexico, having been dubbed “feeble” and found out as a woman. Some discovered women were similarly discharged without trial. Others faced long prison or mental institution sentences. For Williams, the biggest backlash was from her fellow privates. “The men all wanted to get rid of me after they found out I was a woman,” she said. “Some of them acted real bad to me.”

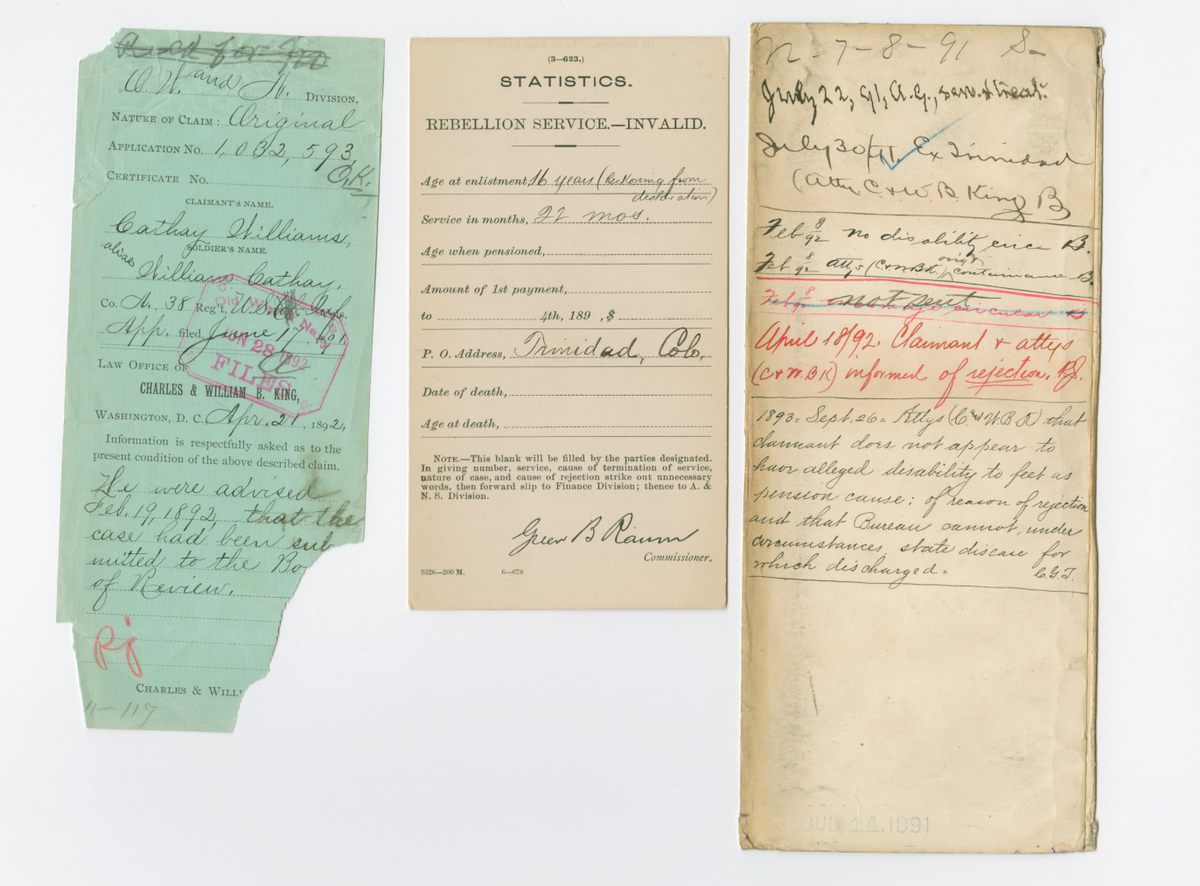

Williams went back to cooking and washing in Pueblo, Colorado. There she got married, but the marriage didn’t last. “He stole my watch and chain, a hundred dollars in money and my team of horses and wagon,” Williams said of her husband. She applied for a disability pension on the grounds of deafness, rheumatism, and nerve damage in 1891, but her claim was rejected the following year. Though a pension medical examination found that all her toes on both feet were amputated, from what circumstances and when is still unknown. The Pension Bureau ruled no disability existed, and denied her claim.

After that, there’s not much recorded about her life. Historians are lucky enough to have a few documents, and estimate she died in Trinidad, Colorado, between 1892 and 1900.

It took nearly a century after her death until historians learned of her tale. Upon discovery, a mythos around Williams emerged. Soon, artists such as William Jennings drew imagined renderings of her with unrealistically sleek, relaxed hair dressed in a slim blue Zouave uniform. Jennings painted her “to highlight and honor the triumphs, trials and tribulations of women in the military.” There are insufficient descriptions, photos, or paintings of her, so the drawings are mere conjecture, and this guesswork fuels various narratives about her.

In the 2002 book Cathay Williams: From Slave to Female Buffalo Soldier , historian Phillip Thomas Tucker attempted to document Williams’s life and largely speculated she was an unforgotten hero who “can be viewed as a pioneer for the thousands of American women serving in today’s United States’ armed forces.” In a book review, author Sarah Eppler Janda wrote that “Tucker fails to demonstrate what was so noteworthy about this one woman who pretended to be sick in order to avoid service that she herself willingly entered.” Others have further claimed she saved her fellow privates from outlaws and was awarded for her bravery.

Frank Schubert believes these historians are projecting Williams’s story to fit a certain worldview based on little information and turning an average soldier into a larger-than-life model, especially compared to black figures like Bessie Coleman, Mary Hamilton, Ida B. Wells, and other Buffalo Soldiers. He adds that the lack of inclusion and representation in black history portrayals shouldn’t deflect focus from lesser-known figures that have sacrificed far more for the black community.

“She’s extraordinary in a way because she took this great risk of joining the army, but it doesn’t make her a hero,” he says. For Blanton, it’s important to look at changing perspectives as historians. She says, “we all define hero the way we define hero, but we have to look at the context of her time. What would be common for a woman today, to do that then, was extraordinary.” In the face of racism, sexism, and more, her simple act was significant for her time.

Williams wasn’t intending to be a hero or highlight a cause when she joined the army. As a former slave with no education, she simply wanted “to make her way through the world,” as Blanton points out. There were probably more black women like her, whose words were never written down.

In 2016, on a hot June day, the Richard Allen Cultural Center and Museum in Leavenworth, Kansas, unveiled a bronze bust of a Buffalo Soldier. It’s a new addition to the Center’s several monuments of Buffalo Soldiers. This statue is different, though. It’s carved in the presumed likeness of Cathay Williams or William Cathey. Either is fine.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook