All Eels in America and Europe Come From the Bermuda Triangle

But no one’s ever seen them there.

Emily Finch is a doctor of geology, but she has recently changed her Twitter handle to “Dr Eelmily Finch.” That’s because she has fallen head over heels for eels: “I’ve been greeting strangers with ‘DO YOU KNOW ABOUT EELS?’ Well, consider yourself a stranger in my path. Strap in.”

An eel army marches on its stomach

Here are some of the fascinating did-you-knows about eels (aka Anguilla) that she goes on to rattle off, with the manic passion of the recently converted (aka the Eel-luminati):

- “ALL the eels in Europe and America are born in the Sargasso Sea (in the Bermuda Triangle! Ominous? Yes). Eels might even live in a landlocked part of Europe and yet they will travel thousands of kilometres over land (yes, land!) and sea to get to the Sargasso Sea to spawn.”

- “Eels just need a bit of dampness on the ground to travel over land. They can even CLIMB UP DAM WALLS! Have you seen how big dam walls are??!”

- Wherever eels live in the world, they just wake up one day, DISSOLVE THEIR STOMACHS, and decide to start their incredibly long journey to their spawning place. They travel all those many thousands of kilometres LITERALLY EATING THEMSELVES ALIVE FROM THE INSIDE!”

- “Even though mature eels die once they spawn (fair enough; no stomach), their offspring return to the place where their parents lived, many thousands of kms away. HOW DO THEY KNOW WHERE TO GO??!”

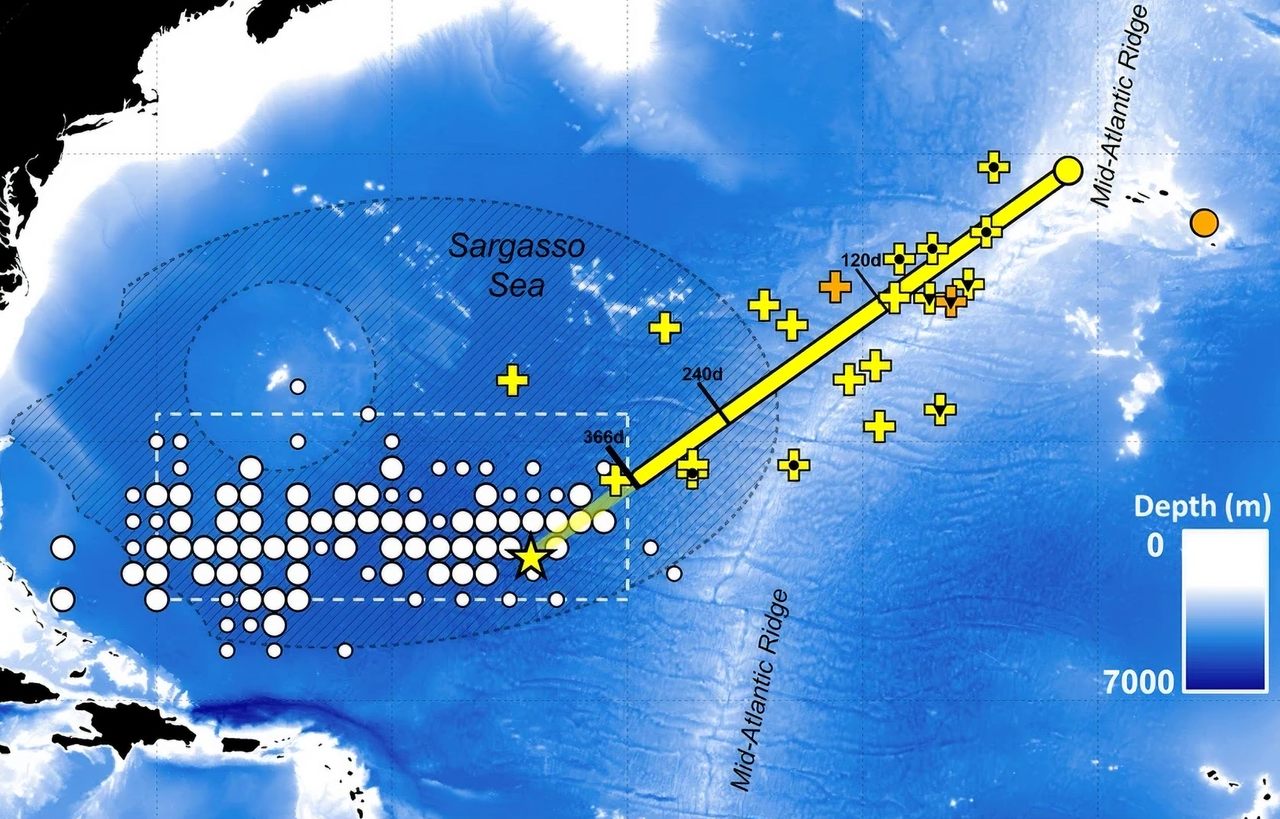

- “A man named Johannes Schmidt originally discovered that eels spawned in the Sargasso Sea by surveying the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea and finding younger and younger eels until he finally found the youngest eels in the Bermuda Triangle.”

- “Despite Schmidt’s discovery almost 100 years ago, no one has ever been able to find direct evidence that eels spawned in the Sargasso! Scientists tried to track eels using trackers, but the eels always mysteriously disappeared…”

- “UNTIL THIS WEEK! Researchers were finally able to track European eels all the way to the Sargasso Sea using satellite trackers! Despite this, NO ONE HAS EVER PHYSICALLY SEEN A MATURE EEL IN THE SARGASSO SEA!”

The news that rocked Dr. Finch’s world was reported by Scientific Reports, in an article published on October 13 titled “First direct evidence of adult European eels migrating to their breeding place in the Sargasso Sea.”

Perplexing thinkers from Aristotle to Freud

“The mystery of how the eels reproduce and the location of their breeding place… has perplexed generations from Aristotle to Freud,” the article says. (In his early years, Freud indeed studied the sexual anatomy of eels—because of course he did.)

Schmidt’s early-20th century surveys narrowed down that search to the Sargasso Sea, situating eel spawning grounds in an area in the western Atlantic between 65° and 48° longitude west, “for here and here only are the youngest, newly hatched larvae found.” However, in the decades since the publication of Schmidt’s findings, in 1923, nobody had ever managed to observe either eggs or adult eels in the Sargasso Sea. So, where exactly are those spawning grounds?

Scientists have tried tagging eels as they migrate since the 1970s, but that has become practical only with the development, over the last 10 to 15 years, of so-called Pop-up Satellite Archival Tags (PSATs). These tags release their data only when they rise to the surface after a predetermined period of time.

Recent studies used PSATs to track more than 80 European eels migrating from the Baltic, Celtic, and North Seas, the Bay of Biscay, and the western Mediterranean. The data from those studies shows how the migration routes of these eels, despite their different origins, converge once they’ve passed the Azores. However, these eels took more than six months to reach their final destination—too slow for the PSATs to identify those elusive spawning grounds.

2,500 kilometers to mate, spawn, and die

The solution: Tag the eels that have a head start. In 2018 and 2019, the authors of the Scientific Reports article fitted PSATs to 26 female eels (which were larger and thus more easily taggable than males) in the Azores, the Portuguese island group halfway between Europe and the Sargasso Sea. These eels “only” needed to swim 2,500 kilometers (~1,500 miles) to their presumed spawning grounds.

Although some trackers got lost (and some eels got eaten) along the way, the researchers were able to follow some for up to a year, providing direct evidence of adult European eels (Anguilla anguilla) reaching their presumed breeding place in the Sargasso Sea—a first.

This finding may prove critical in learning more about the migratory routes of these creatures. At distances between 5,000 and 10,000 kilometers (3,100 to 6,200 miles), this is the longest migration of all anguillid eels. At present, very little is known about the routes or the timing of these migrations, the speed at which the eels swim, and most intriguingly, their navigational methods. (Temperature? Magnetism? Terrain? Smell?)

Better knowledge may in turn help preserve the species. Having suffered a 95% decline since the 1980s, the European eel is now critically endangered.

An island named after eels

Not to end on a downer (and to encourage more eel-thusiasm), here are ten more fascinating facts about eels:

- Eels look like snakes, but they’re actually a (narrow, almost finless) type of fish.

- After a larval stage, young eels have a transparent phase, as glass eels.

- Baby eels, when a bit older, are called elvers.

- There are over 800 different species of eel.

- They range from very small (5 centimeters or 2 inches) and slight (30 grams or 1.1 ounces) to the very large (4 meters or 13 feet) and heavy (25 kilograms or 55 pounds).

- Some species of eel can live up to 85 years.

- Electric eels, which live in South America, technically aren’t eels. They belong to the order of the Gymnotiformes, which is different from the Anguilliformes, to which true eels belong.

- Eels swim by generating body waves. They can reverse the direction of these waves, meaning they can both swim forward and backward.

- Eel’s blood contains a toxic protein that cramps muscles, including the heart. In other words, eel’s blood can kill. Never eat raw eel.

- Anguilla, a Caribbean island that is a British Overseas Territory, got its name because of its eel-like shape.

Read the entire article here in Nature.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook