Tiberius, Imperial Detective

In ancient Rome, murder was a private business, unless the emperor took an interest in the case.

This story is excerpted and adapted from the new book A Fatal Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum: Murder in Ancient Rome by Emma Southon, PhD, published by Abrams Press © 2021.

Like all the best detective stories, the story opens with the body of a woman being found in Rome in the early hours of the morning, around A.D. 24. The sun was rising, the birds were singing, and a woman’s crumpled body was lying on the ground. The body was that of Apronia, the wife of the praetor Marcus Plautius Silvanus, and she had fallen, somehow, from a high bedroom window and not survived the fall. This was suspicious. Apronia was the daughter of Lucius Apronius, who was a very important man in Rome. He had enjoyed a very successful military career in Germany and Dalmatia, and had jointly put down a revolt in Illyricum. For this act, he had been granted the right to wear Triumphal Regalia, which was a really special outfit. Being the daughter of a man who was allowed to wear the special outfit was a bit like being the daughter of Brad Pitt; everyone wanted to marry Apronia so they could hang out with her dad. Her dad had chosen Silvanus, who was a man doing well for himself. He was a praetor, which is just below consul in terms of prestige, and the fact that he married the daughter of Apronius suggested that he was a man on the up.

Unfortunately for Silvanus, Apronia died painfully, hitting the Roman ground hard. Even more unfortunately for Silvanus, Apronius did not believe that his daughter, his good Roman daughter of excellent stock, had simply stumbled and fallen out of her bedroom window in the middle of the night by accident because that is a ludicrous thing to happen. Nor did Apronius, and please imagine here the most clichéd upstanding Roman man you can, a straight-backed, no-bullshit military man in his fine purple toga, think that his daughter had deliberately defenstrated herself, which was Silvanus’s version of events. He believed that Silvanus had pushed her. He believed this strongly enough that he wanted Silvanus prosecuted for it. And he wanted this taken all the way to the emperor—Tiberius.

Now, you’ll note that we have already diverged from what we may expect the narrative to be. In our murder mystery stories, the dead woman is found in the prologue and chapter one opens with the grizzled alcoholic detective examining the crime scene; but no police will appear to investigate Apronia’s suspicious death. There was no representative of the state of Rome who would get involved in this case until Apronius took it to the emperor because, as far as the Romans were concerned, the murder of wives, children, husbands, or really anyone at all was absolutely none of their business.

This is a useful demonstration of how fundamentally differently we view the role of the state to the Romans, and how we differentiate between public and private business. To most of us, it is obvious that the state has a responsibility to keep its people safe, and that it uses the apparatus of the police and the justice system to do this. When someone is murdered, the police investigate, the prosecution service prosecutes, and the prison service takes the murderer away and keeps them locked up until they are judged to be safe. The relatives of the victim aren’t expected to get involved because murder is a public business. The state has two broad functions here: It dispenses justice and punishes the wrongdoer, thus rebalancing the scales of justice, and it protects the people of the state by identifying a cause of harm and preventing it from causing further harm. In much the same way, the state is also now expected to make sure that rotten food isn’t sold in shops and substances judged to be dangerous, like heroin, aren’t freely available. We pay taxes so the state will keep us safe. On the other hand, we don’t expect the state to be getting all up in our bedrooms, legalizing who women can have sex with or rewarding women with public honors for having children. That’s private.

The Romans, however, saw things very differently. Rewarding women for babies was A-OK, making laws about how much jewelry a girl could wear was just sensible policy. But murder? That was family business. If a woman was murdered by her husband, it was her guardian’s job to work that out, find a prosecutor (or act as one), and take him to court if the family wanted to or arrange a fair compensation to be paid if not. There were no police to come and gather evidence or prisons to put dangerous people into, in the same way that there wasn’t a Food and Drug Administration or Food Standards Agency to make sure that tavernae weren’t poisoning people with old meat and that children couldn’t buy knives. That sort of thing was up to the gods and the individual.

The justice system in Rome was one based purely on personal responsibility. The individual was responsible for identifying that a crime had taken place, identifying who had committed the crime, and finding a resolution. Success, however, relied on three things. First, the perpetrator had to be identified, then they had to admit that they did it, and then both parties had to agree on an appropriate level of compensation, which the perpetrator then had to actually pay. None of these was particularly easy. And we regularly see in curse tablets what happened when these steps didn’t work out. Curse tablets are bits of lead on which ancient people wrote curses. They then rolled them up, nailed them shut, and buried them at shrines in the hope that a generous god would smite the person who thieved their pot. An awful lot of them were written by people who were super pissed off that someone stole their pig/gloves/favorite shoes and asked the gods to bring pain and death to that person. The personal responsibility system was a system with flaws. It also allowed some people to have more access to justice than others. Like Apronius.

Now, Apronius could have had a sit-down chat with Silvanus himself and worked out some compensation between them, but Apronius was, as previously mentioned, very important and he wanted more. He wanted public justice to be done and for everyone in Rome to know that Silvanus was a murderer and his daughter a victim. Luckily for him, he had the imperial access to make that happen. In addition, Silvanus was now acting very weirdly indeed. Apronius managed to have Silvanus pulled up in front of Tiberius for questioning very quickly, which would speak to his power and influence by itself. Emperors like Tiberius usually spent their time worrying about what entire provinces and colonized countries were doing, not what one idiot praetor did in his house. Most of the time, anyway.

Tiberius was a grumpy old man, pretty much from birth, but seemed to have absolutely loved a mystery. He was a budding Miss Marple of the Roman world and something about this case caught his attention and he got really invested in it. This might have been because Silvanus’s grandma was Tiberius’s mother’s best friend. Livia and Urgulania (Is this the worst name in history? Quite possibly yes.) were inseparable, and Livia was more than a little influential in her son’s early reign. Or it might have been that he just really liked Apronius. First, Tiberius questioned Silvanus about what had happened to poor Apronia and Tacitus (the historian who documented all this 80 years later) tells us that Silvanus gave an “incoherent” answer in which he claimed that he had been fast asleep the whole time but he assumed his wife had killed herself.

Unfortunately for us, it’s not recorded why he thought his wife might defenestrate herself while he was sleeping. Maybe his snoring was awful. Tiberius didn’t believe him. We know this because he did something really unusual: He went to look at the crime scene.

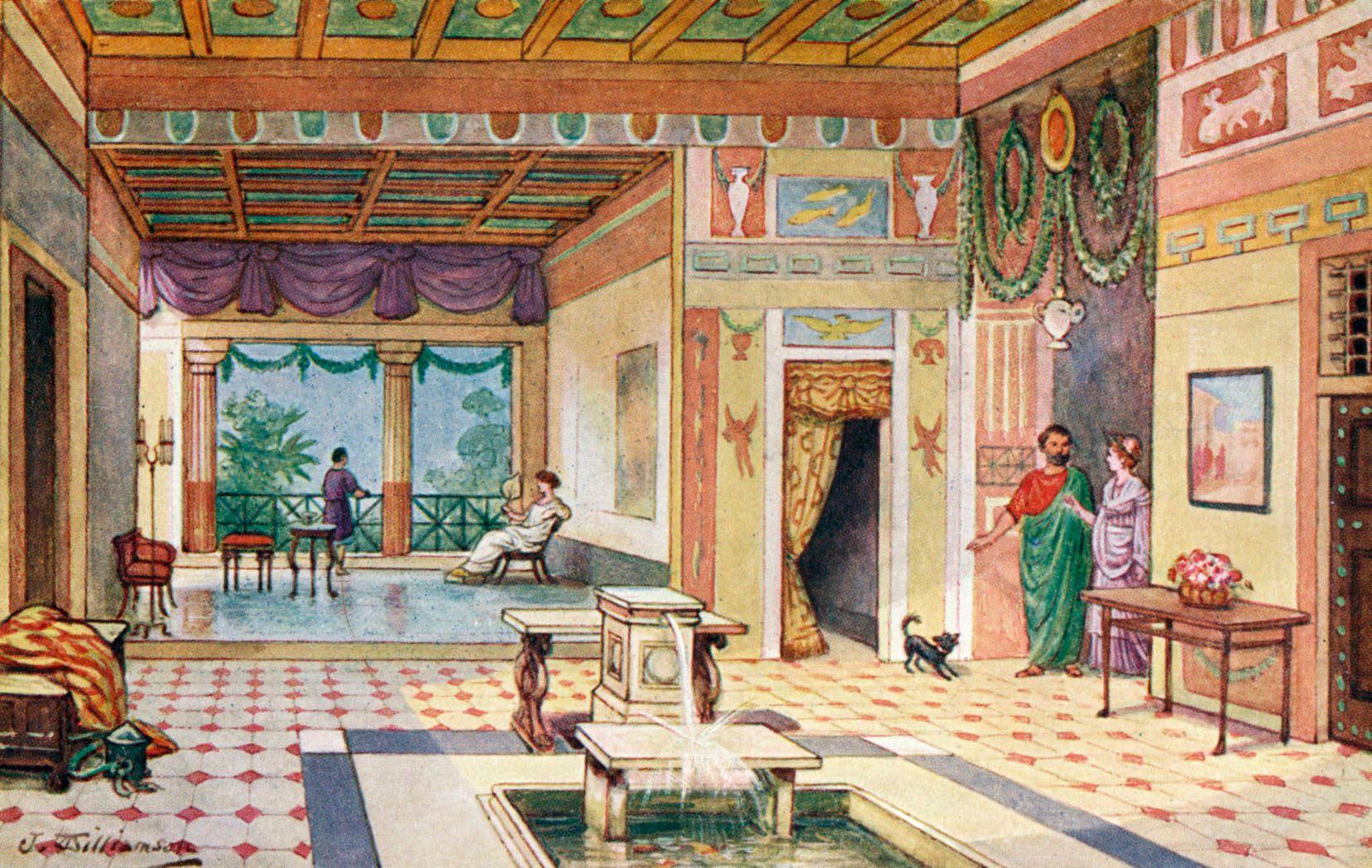

This is, I believe, the only time in recorded Roman history that an emperor decided to investigate a murder by examining the scene of the crime. These things just didn’t happen in Rome because they didn’t have the same ideas about evidence and crimes that we have. Their murder trials didn’t involve people looking at daggers or gloves or other bits of physical evidence. They just involved people reciting really good speeches at each other, each using the same rhetorical strategies, mostly about the character of the defendant and/or victim and their general demeanor in life rather than the actual events of the case in question, until the jury or judge picked whichever person they liked best. Examining a crime scene wasn’t a particularly important part of that process. Tiberius going off to have a look at the window from which Apronia fell was therefore very surprising. So surprising, in fact, that Silvanus hadn’t even bothered trying to tidy up after the murder had been committed. The emperor was able to see immediately what Tacitus calls “traces of resistance offered and force employed.” Frustratingly, he does not elaborate on what these signs were. Maybe chairs had been flung across the room, or curtains had been torn down, or there was blood on the soft furnishings. This blows my mind a little bit. Silvanus was a rich man. He had a significant household of enslaved people. And yet he apparently didn’t even bother to ask them to tidy up a bit and make it look rather less like there’d been a fatal incident in the bedroom. No one took it upon themselves to have a wee whizz round with a mop while he was out with the emperor. Presumably, no one expected the august Tiberius to take time out of his busy day being in charge of all of Western Europe and North Africa to nip round for a look. No other emperor would have done this, even for their mum’s best friend’s grandson.

Tiberius just loved a mystery. There are lots of nice stories of Tiberius investigating things that interested him. He pops up in Pliny the Elder’s Natural History (basically an encyclopedia of everything Pliny could think of) investigating some odd sea monsters who appeared due to an unusual low tide around modern Lyon (including sea-elephants and sea-rams, apparently), and in the wonderfully deranged Phlegon of Tralles’s collection of Greek and Roman marvels, making casts of some giant teeth and bones that had appeared in Turkey. The tooth was a foot long, says Phlegon, and Tiberius had a model of the full-sized giant measured from the tooth, making him, as Stanford historian of ancient science Adrienne Mayor points out, the world’s first paleontologist. (The tooth almost certainly belonged to a megalodon.) Tiberius was basically a wannabe Fox Mulder, wanting to investigate any weird thing that got put in front of him, and that included Silvanus’s incoherent story that his wife spontaneously launched herself out of a window while he was innocently sleeping.

One Italian historian has posited another reason why Tiberius might have found this a particularly interesting case, by suggesting that this Marcus Plautius Silvanus might also be the Servius Plautus recorded by St. Jerome in the fourth century as being guilty of sexually assaulting his own son in A.D. 24. If Servius Plautus and Plautius Silvanus are the same person, then he was one hell of a terrible person. He was a man who was caught somehow sexually assaulting his own son—Jerome offers only that he ”corrupted” his son so details are scarce—and then, while facing prosecution for this, killed his wife by hurling her out of a window. And let’s think about the logistics of that for a second. Stop right now and really think about this. Think about trying to bundle up a grown-ass woman, who is presumably not cooperating, and getting all her limbs out of a window without her holding onto the windowsill. Imagine the very physical, very determined fight you would have to have to do that. Even assuming that he had help, this was a hard way to kill someone. It’s a manner of murder that suggests both a lack of foreplanning and a serious dedication to killing the victim. And if Servius and Silvanus were the same man, perhaps that gave Tiberius (and Apronius) an idea of why he might have murdered Apronia. It’s easy to imagine a wife who is deeply unhappy with her sexually abusive husband and the fight that might arise as a result. The surprising thing is that it would happen within such a “respectable” family home, where emotional control and maintaining face were important cultural behaviors.

But apparently it did happen, and Tiberius found the evidence and sent Silvanus to the Senate to be tried officially and sentenced. (He was maintaining a facade of pseudo-democracy at the time.) Silvanus was not destined to face a trial, though. His grandmother Urgulania intervened and politely sent him a dagger. This parcel was taken as a not-very-subtle hint from both his family and the emperor that Silvanus should save everyone some time and money and honorably punish himself with a quick dagger to the heart. Silvanus was not dedicated to the idea of killing himself, probably his most relatable opinion, and after failing to stab himself (again, relatable) he had an enslaved man cut his wrists for him. Whether justice was served is rather a matter of opinion. He lost his life, but there is certainly the feeling that by being allowed to die at home by his own hand and avoid the spectacle of a trial, he rather got away with it. It feels like history let him get away with it a bit, too.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook