Seven Lost Cities Swallowed Up By Time

The rediscovered ruins of civilizations past.

Hidden in the depths of the sea, buried under hillsides, swallowed up by the jungle, or consumed by the wrath of the heavens, lost cities have fascinated ever since Plato told the story of Atlantis:

Now in this island of Atlantis there was a great and wonderful empire which had rule over the whole island and several others. […] But afterwards there occurred violent earthquakes and floods; and in a single day and night of misfortune all the warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea.

Many people have gone in search of lost cities, believing in tall tales and ancient legends. Con men, archaeologists, showmen, and adventurers have traveled over the mountains of Afghanistan, through the jungles of Cambodia, across the deserts of Jordan, and into the very strangest parts of the world, full of hope. Here are seven of the world’s most fascinating lost cities.

Troy

CANAKKALE, TURKEY

Troy, city of heroes, was the setting of Homer’s epic Iliad. The story of the Trojan War—of the wrath of Achilles, of love and revenge, and men who would make war on the gods themselves for pride—is a foundation-stone of Western literature. It has echoed through poems and histories and paintings and films. But Troy itself remained a mystery—until one man went in search of it.

Heinrich Schliemann was not your typical archaeologist—even by the swashbuckling standards of the 19th century. A trader and wheeler-dealer, he made his fortune buying and selling everything from indigo dye to gold-dust. He had an eye for a tall story, and was never one to let facts stand in the way. (He wrote a hair-raising account of his experience in the San Francisco fire of 1851—but he was nowhere near San Francisco at the time.) In 1868, he went searching for the ancient world.

The site he settled upon for the location of Troy, the Turkish village of Hisarlik, was suggested by British archaeologist Frank Calvert. Schliemann commenced excavations in 1871. He worked on a brutal scale, throwing huge trenches across the hillside, and tunneling down through layer after layer of finds in search of Homeric Troy. Soon, gold and precious ornaments were piling up. He named them “Priam’s Treasure” after the legendary king of Troy, and dressed his wife in them.

There was only one problem: Troy II, Schliemann’s city of Homer, was an early bronze age city, from around a thousand years before any historical Trojan War could have taken place. Schliemann had, essentially, dated the Beatles to 960 AD. Even his limitless self-belief faltered in the face of the evidence. It is now thought that another layer of the city, Troy VII, is closest to the “Homeric” Troy. Alas, Schliemann, contemptuous, blasted straight through it in his search for the wrong lost city. He may have done more lasting damage to Troy than Homer’s Greeks ever did—but enough still remains for visitors to glimpse the power and pride of this once stunning place.

Knossos

HERAKLION, CRETE

Few cities can match Troy for the stories that have been told about it, but Knossos is one of them. Home of the Minotaur—that dreadful half-man, half-bull of Greek mythology—and the impossible labyrinth of Daedalus, it has been a place of mystery for thousands of years.

Legend was not enough for Arthur Evans, a British archaeologist and friend of Schliemann. In 1900, he traveled to Crete in search of King Minos and his wondrous palace. In the north of the island, close to the present-day city of Heraklion, his hopes were rewarded. Over the course of 25 years, he uncovered layer after layer of finds, including the ruins of a rich palace. The site had first been inhabited around 7000 BC.

The ruins of Knossos attract today, over a million visitors a year who gaze up at the columns of the palace, and gape at the rich blues of the frescoes with wonder. There is one small problem: both palace and frescoes are not the work of Daedalus and his artisans, but of Evans and his team of 20th century craftsmen. Hardly a square inch of the famous paintings is original. The author Evelyn Waugh, visiting in 1930, remarked that, “It is impossible to disregard the suspicion that their painters [of the restored frescoes of Knossos] have tempered their zeal for accurate reconstruction with a somewhat inappropriate predilection for covers of Vogue.”

As for the “ancient” palace, as Cathy Gere wrote, it actually “enjoys the dubious distinction of being one of the first reinforced concrete buildings ever erected on the island.” Knossos today, though a fascinating place to visit, is the city of Arthur Evans—not King Minos.

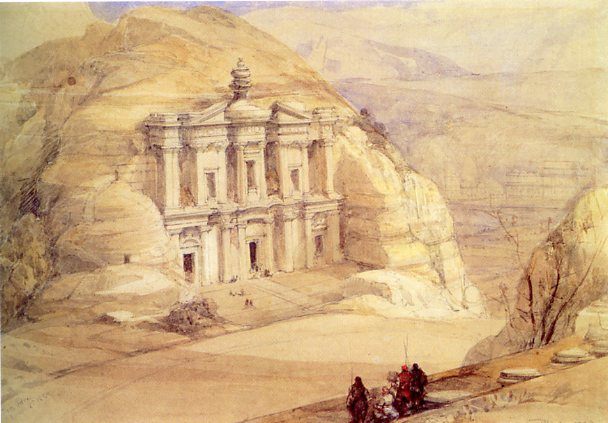

Petra

MOUNT HOR, JORDAN

The “rose-red city, half as old as time,” with its spectacular rock-cut temples—glowing and impossible, in the middle of the desert—was unknown in the West until 1812. It was rediscovered, more by accident than by design, by a young Swiss adventurer called Johann Ludwig Burckhardt.

Burckhardt really wanted to be in Africa; his greatest ambition was to discover the source of the River Niger. But circumstances conspired against him. In Malta, he heard of another traveler who had vanished into the East, in search of Petra. Burckhardt decided to follow him. He learned Arabic in Aleppo, disguised himself as a Muslim, called himself Sheikh Ibrahim Ibn Abdallah, and set off.

He crisscrossed the Middle East, asking for news of his city wherever he could, until he heard of a path leading into the mountains, not far from the tomb reputed to belong to Aaron, brother of Moses. Under cover of sacrificing a goat to Aaron, he made his approach—and Petra opened up before him. His jaw dropped and he scribbled down notes as fast as he could. So eager was Burckhardt that his local guide began to look at him suspiciously. Burckhardt collected himself, and resumed his pilgrim’s guise. The act had to be maintained. The goat had to die.

In Europe, news of the rediscovery of Petra met with fascination and delight. In the Middle East, Burckhardt’s “discovery” had been known of for hundreds of years: Sultan Baibars of Egypt had visited Petra in the 13th century, five hundred years before Burckhardt. Lost cities are sometimes only lost to some—and heroic Western narratives of their “rediscovery” are not always what they seem.

Gedi

NEAR MOMBASA, KENYA

Not all lost cities, of course, are as well preserved—or as well-known—as Petra. The ruins of Gedi rest near the coast of Kenya, surrounded by tropical forest—inscrutable and almost impenetrable. A grand palace, a sumptuous mosque, and streets and houses can be glimpsed amongst the trees—the remains of what was once an astonishing city.

Chinese coins and Ming pottery, Venetian glass, trade goods from India and from as far afield as Spain have been found within the ruins. Gedi was clearly a flourishing commercial centre for many years, from around the 14th century to the 17th century. But almost nothing is known for certain of the life of the city, or of its inhabitants.

The city was abandoned twice: why, no one knows for sure. Soon, the trees crept back in. Today, visitors wander amongst the ruined houses, stooping to read half-faded inscriptions in Arabic, telling one another tales of what might have been.

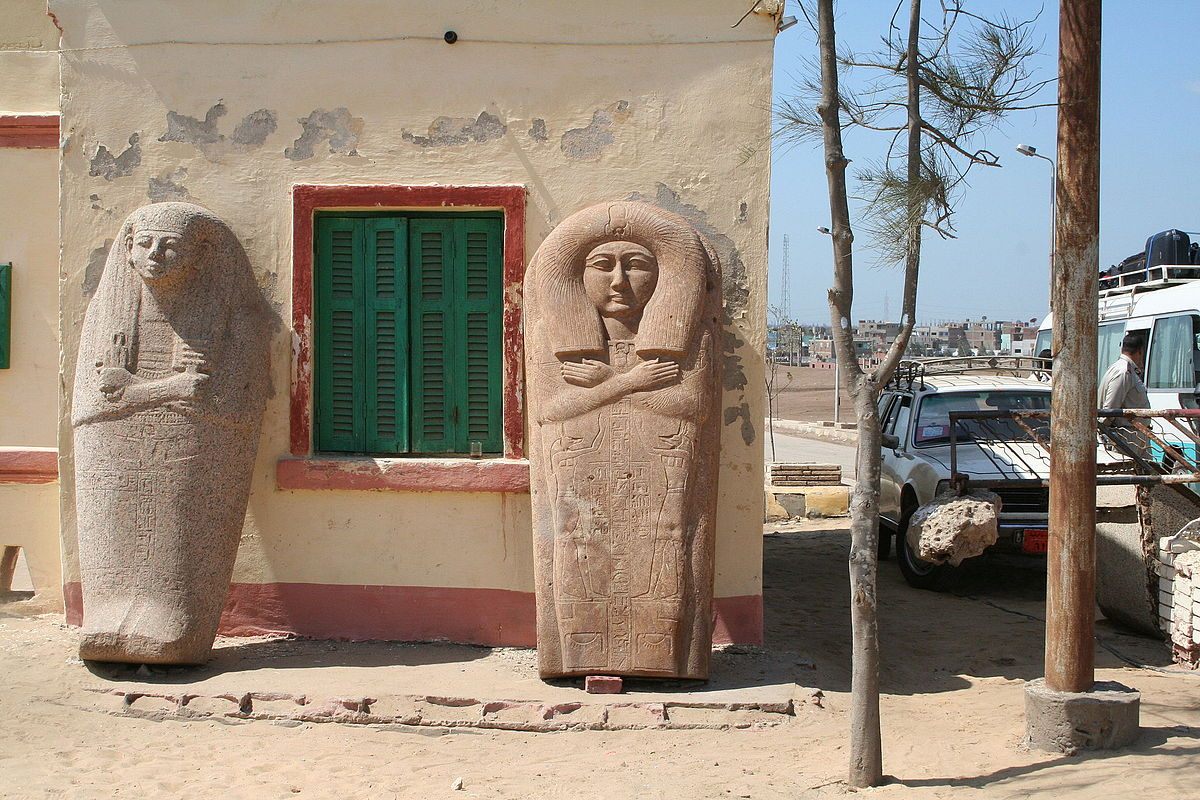

Tanis

TANIS, EGYPT

Some lost cities are all the more tantalizing in their absence. Atlantis, the city of legend, can be whatever people want it to be. More than a few would be disappointed, if it was actually found and understood. So it has been with Tanis, a city more lost in fiction than it ever was in fact.

Tanis, as everyone who has watched Indiana Jones knows, is where one may find, in no particular order: the Ark of the Covenant, Nazis, and an Egyptian city “consumed by the desert in a sandstorm that lasted a whole year. Wiped clean by the wrath of God.” Only, it wasn’t, and it hasn’t been.

Tanis was built around 1000 BC, if not before, as a brand-new capital city for Egypt. There, pharaohs were buried for generations in some of the most spectacular and well-preserved royal tombs which have survived in Egypt: wonders of silver coffins, gold masks, and intricate jewelry. Power, however, gradually shifted away from Tanis—and the capital of Egypt was moved to Memphis. Bypassed by traders, gradually forgotten, the city slipped into ruins, and the ruins were buried beneath the desert.

It was in the 19th century that the mysteries of Tanis began to be unraveled: two archaeologists, Auguste Mariette and Flinders Petrie, discovered the location of the city, and began to excavate its ruins. Since then, Tanis has gradually yielded up astonishing treasures: jewels, tombs, temples, and Sphinxes. Tanis today can be a fascinating place to visit, little known by tourists—a symbol of the scale, and the limits, of ancient Egyptian power.

Angkor

CAMBODIA

Cambodia is the closest you can get, today, to your own real life Indiana Jones movie. There, the temples of Angkor seem built into the fabric of the forest itself, bats flap their leathery wings in the vaults, and incense drifts down the empty colonnades.

The god-kings of Angkor were at the height of their powers from the 9th century until the 15th century. In that time, they built the largest preindustrial city in the world in Cambodia: larger than Rome, larger than Alexandria, larger by far than London or Paris at the time. Wealth was poured into ever more spectacular temples, replete with intricate carvings and statues. In the fifteenth century, for reasons which still puzzle scholars today, the gigantic complex was left almost entirely abandoned—lost to the jungle.

Early Western visitors, glimpsing the astonishing structures looming up amidst the trees, were left almost speechless. For António da Madalena, Angkor was “of such extraordinary construction that it is not possible to describe it with a pen, particularly since it is like no other building in the world.” Since the 19h century, a slow process of restoration has been taking place. While tourists flock to Angkor today, much of the site remains to be discovered, and the trees loom on all sides, ready to swallow the city up again.

Alexandria on the Caucasus

AFGHANISTAN

In 329 BC, Alexander the Great founded a city on what was, for him, the edge of the known world. Alexandria on the Caucasus was established in modern-day Afghanistan—and Alexander settled it with 3,000 veterans of his campaigns.

Alexander never returned. A few years later, he was dead in Babylon. His control of Afghanistan had always been fleeting at best. After his death, his empire fragmented, and Alexandria on the Caucasus was swiftly forgotten by his successors. Ancient accounts of this part of the world paint a picture of a wondrous, magical land: where a city founded by the god of wine himself lay nearby, there were men with no heads, and naked philosophers imparted wisdom. It was a fitting place for a lost city.

Alexandria of the Caucasus was rediscovered by perhaps the unlikeliest character of all these explorers. Charles Masson was a deserter from the British army—and a virtuoso con artist. He wandered 19th century Afghanistan in a succession of disguises: a faquir, a Frenchman, a spy, a Haji, an American, a healer. (No portrait of him survives.) Obsessed with Alexander the Great, Masson searched Afghanistan for years for the cities which he had founded. In July 1833, he discovered Alexandria on the Caucasus on the plains north of Kabul.

Masson recovered thousands of coins and artifacts from the site, many of which are now in the British Museum. But little today remains of this, the most elusive city of all. For Alexandria on the Caucasus is now almost entirely buried beneath Bagram air base. Its streets and temples lie somewhere below the tarmac and concrete, waiting for the moment when they will be rediscovered once more.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook