Extreme Bagpiping Situations, From Antarctica to the Beaches of D-Day

Members of the 7th Seaforth Highlanders, 15th (Scottish) Division during Operation Epsom on June 26, 1944. (Photo: Laing (Sgt)/Imperial War Museums)

In early November, NASA astronaut Kjell Lindgren performed a stirring bagpipe rendition of Amazing Grace while floating aboard the International Space Station.

In doing so, Lindgren became the first person to play bagpipes in space. But he is far from the first to play the instrument in an inhospitable environment, under trying circumstances. For the ultimate examples of extreme bagpiping, we turn to the stories of two Scottish musicians from the last century: Gilbert Kerr and Bill Millin.

In November of 1902, the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition set sail from Troon, Scotland, to explore the great white land at the bottom of the world. Among the 25 voyagers to board the good ship Scotia was Gilbert Kerr, the expedition’s official piper. Kerr was a valued member of the team, as described in The Voyage of the “Scotia,” an account of the expedition published in 1906. During the early days of the maritime journey, Kerr “marched gallantly up and down the foc’s’le-head” of the ship, “blowing a stirring march to cheer our drooping spirits.”

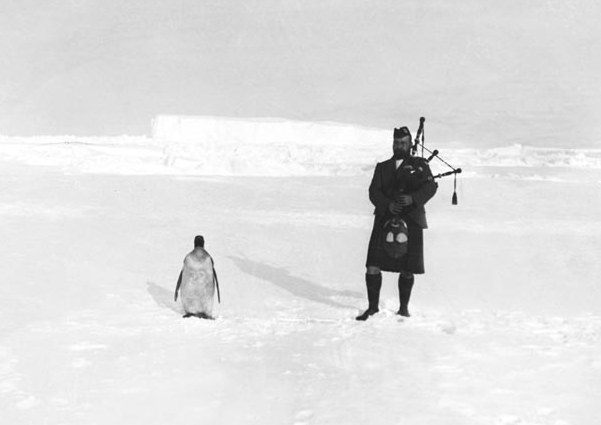

When the ship finally reached Antarctica in March 1904, Kerr continued to entertain the cold and homesick crew. On March 9, their ship became trapped in ice. While his expedition mates figured out what to do, Kerr donned a kilt, traditional furry pouch, and knee socks, grabbed his pipes, and shuffled through the snow toward a group of emperor penguins. He proceeded to serenade the birds with a wide variety of traditional Scottish tunes, but “neither rousing marches, lively reels, nor melancholy laments seemed to have any effect on these lethargic, phlegmatic birds,” said The Voyage of the “Scotia.” Furthermore, the penguins exhibited “no excitement, no sign of appreciation or disapproval, only sleepy indifference.”

The moment was captured in the photo below:

Gilbert Kerr plays his heart out for an unappreciative emperor penguin. (Photo: William S. Bruce/Royal Scottish Geographical Society)

Though it may appear that the penguin pictured stood beside Kerr of his or her own volition, the Glasgow Digital Library notes that the animal was “sufficiently reluctant as a listener to require tethering to a large cooking-pot packed full of snow.” (These days, with the wildlife-conserving Antarctic Treaty System in effect, a piper would probably get in trouble for tying a penguin to a pot. The British Antarctic Survey specifically prohibits its personnel from engaging in “harmful interference” with the local fauna.)

The bagpipes Kerr played on the ice ended up back in his mother land, where they were presented to the 1st Edinburgh Battalion of the Royal Scots in 1914, just as the First World War was heating up. When the Battle of the Somme broke out in France in 1916, the same pipes were played on the field. They were subsequently lost in the melee, a battle in which over a million combatants were killed and no one much cared about the whereabouts of some well-traveled bagpipes.

The mournful sound of bagpipes also resonated on the battlefields of World War II, most dramatically in the case of Bill Millin, a Scottish piper who played on D-Day as he and his fellow Allied soldiers stormed the beaches at Normandy. Then aged 21, Millin was a private in the British Army’s 1st Special Service Brigade and personal piper to Lord Lovat, the brigade’s commander. According to the Independent, when D-Day dawned, Lovat told Millin to defy English War Office orders that forbade the playing of bagpipes on the battlefield. ”You and I are both Scottish so that doesn’t apply,” the commander reasoned.

Duly instructed, Millin, unarmed and wearing a kilt, played his bagpipes as he and his brigade mates rushed onto Sword Beach under German fire. Even as friends fell to the ground around him, Millin kept piping to keep his fellow soldiers’ spirits up. “Among all the noise and bedlam going on I could hear bagpipes,” brigade member Ken Sturdy told the Guardian. “It was certainly heroic.”

Millin, at right, storming the beach at Normandy on June 6, 1944. (Photo: Evans, Captain J L /Imperial War Museums)

After Millin had waded through the icy water, kilt ballooning, and landed on the sand, he began to walk up and down the beach, still playing his bagpipes. These actions apparently so baffled the Germans that they didn’t shoot at him because they believed he had, in the words of the Telegraph, “gone off his head.”

Though the Germans didn’t understand the bagpipe thing, the British commandos storming Sword Beach clung to the dolorous sounds as a way to make sense of the chaos. As Millin’s 2010 obituary in the New York Times noted:

“‘I shall never forget hearing the skirl of Bill Millin’s pipes,’ one of the commandos, Tom Duncan, said years later. ‘As well as the pride we felt, it reminded us of home, and why we were fighting there for our lives and those of our loved ones.’”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook