Decoding the Success of a Picture Book About Monsters and Trolls

There’s a reason John O’Brien’s 1977 illustrations still have obsessed fans.

If you want to create a bestselling children’s book that will routinely receive five-star reviews on Goodreads 40 years after its first publication, the key is to draw it in the style of Hieronymus Bosch.

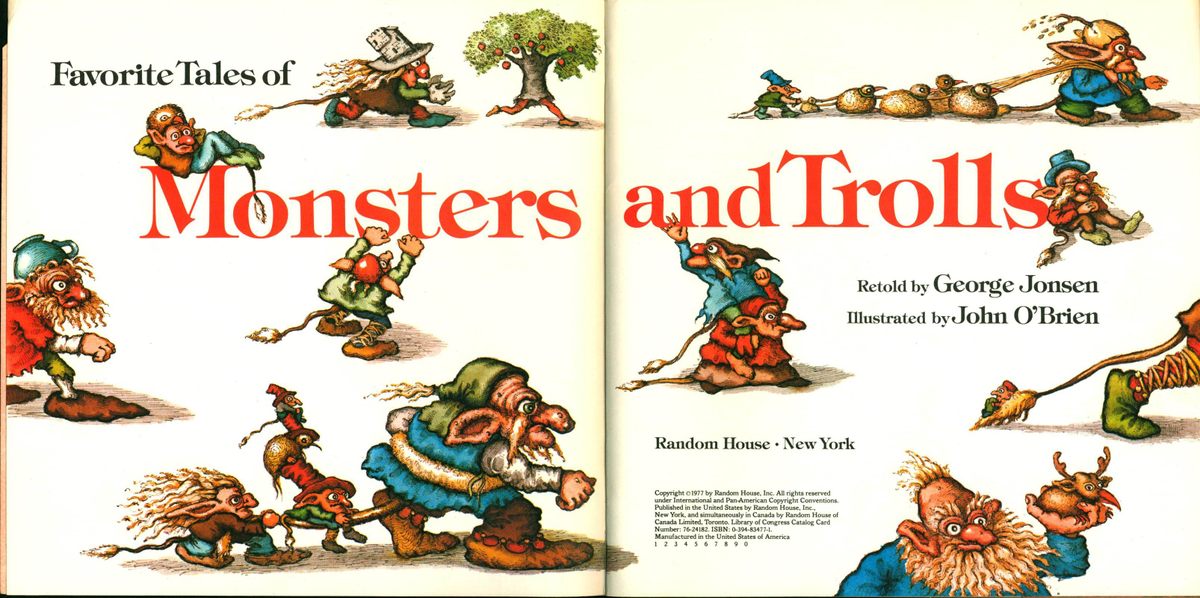

It may seem counter-intuitive to mimic the hellscapes and grotesqueries of such paintings as The Garden of Earthly Delights or The Last Judgment for a children’s book, but the plan sure worked for John O’Brien. He’s the illustrator behind Favorite Tales of Monsters and Trolls, a 32-page picture book first published in 1977 by Random House. To this day, nostalgic readers still go online to enthuse about it.

Monsters and Trolls recounts three popular Scandinavian folk stories featuring trolls. Undoubtedly the most well-known is the opener, “The Three Billy Goats Gruff,” but what sets this telling apart are O’Brien’s fantastic illustrations: here the troll is an anthropomorphic toad who keeps prisoners in his stovepipe hat and keeps an odd bird-of-paradise for a pet. Both goats and troll must step carefully to avoid treading on gnomes, kiwi birds, and even stranger dwellers of the baroque Wonderland they inhabit.

“You just have all of these little creatures and peoples, communities of fairy folk occupying every corner of the pages,” says the writer Robert Lamb, who grew up with the book and today reads it to his son. “As an adult, I dig the Bosch and Breughel elements in the illustrations, but at the time it was just the richness of the visual world.”

“Oh yeah, for sure,” says O’Brien when asked if the busy and bizarre scenes of Monsters and Trolls were explicitly drawn in the styles of Bosch and Breughel the Elder. “I was really into those Dutch painters at the time.”

Monsters and Trolls was O’Brien’s first book out of art school. After graduating from the Philadelphia College of Art, O’Brien began shopping his portfolio to New York publishers. He eventually wound up meeting with the famed children’s book publisher Ole Risom. Risom was from Denmark and had worked in publishing in Sweden before immigrating to the U.S. As a vice president in Random House’s children’s division, he mentioned to O’Brien that he’d always wanted to publish a collection of troll stories he remembered from childhood. Risom thought O’Brien would be perfect for it.

But when O’Brien showed Risom the initial round of sketches for the project, Risom rejected them. O’Brien, worried about jeopardizing his first professional gig, had held himself back from going full Bosch. Risom told him “to go to town” with the weirdness. So O’Brien did.

The book became a collaboration between the two men. Though the text is credited to George Jonsen, no such author ever existed — O’Brien is certain Risom himself wrote it. It’s not an uncommon practice in children’s publishing for editors and publishers to write the text for picture books under pseudonyms.

“It received a lot of attention at the time,” says O’Brien, adding that Monsters and Trolls landed on the New York Times bestseller list for children’s books and went through several reprints. “I got work right away. Once you have a book it’s easier.”

Yet that still doesn’t explain why Monsters and Trolls, out of print for decades, continues to attract glowing reviews today. After all, there have been lots of New York Times bestsellers over the years.

The answer may lie in the fact that O’Brien’s drawings, whether intentionally or not, provoke readers to linger over the pages.

“When something grabs your attention, you look at it,” says Susana Martinez-Conde, a neuroscientist and co-author of Champions of Illusion. This is called an orienting reflex, Martinez-Conde says, and is related to the connection between our eye movements and our attention spans. Crowded images such as O’Brien’s have to be parsed apart — the viewer’s eyes must roam around the page to distinguish between the relevant details and the background, thereby focusing his or her attention.

Books such as Where’s Waldo? or Monsters and Trolls are “very attractive to children, especially to early readers because the writing may not be that sophisticated but they have sophisticated visual parsing,” she says.

And just as attention and eye movement go together, so does attention and memory formation. “It’s very hard to remember something you didn’t pay attention to,” says Martinez-Conde. “If you have a page that is consistently engaging eye movement for long periods of time on multiple occasions, you create an intellectual and emotional experience,” which tend to be remembered later, she says.

As any parent can tell you, children like to read or have the same story read to them over and over. When it comes to battling for a young reader’s time—and attention—Martinez-Conde believes Monsters and Trolls has a leg up on the competition. “Most of the books for children don’t have this level of complex illustration. It’s both a story and a visual puzzle. There’s not much of a narrative in the Waldo or I Spy books.”

O’Brien is hardly a one-hit wonder. Though his style has since moved away from the Early Netherlandish painters and more toward pointillism, he went on to become a regular contributor to The New Yorker, and has illustrated many more children’s books. His latest is Revolutionary Rogues, a history of John André and Benedict Arnold.

Still, O’Brien says that in the past three or four years he’s received many e-mails from fans of Monsters and Trolls.

“One e-mailer said, ‘I always felt bad for the guy in the hat,’” says O’Brien, referring to the final confrontation between billy goat and troll which ends (spoilers) with the troll and his hoosegow headwear plummeting from the bridge. “He also said he was sure the bird was in cahoots with the troll.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook