Fiction’s Newest Frontier: Literary Geocaching

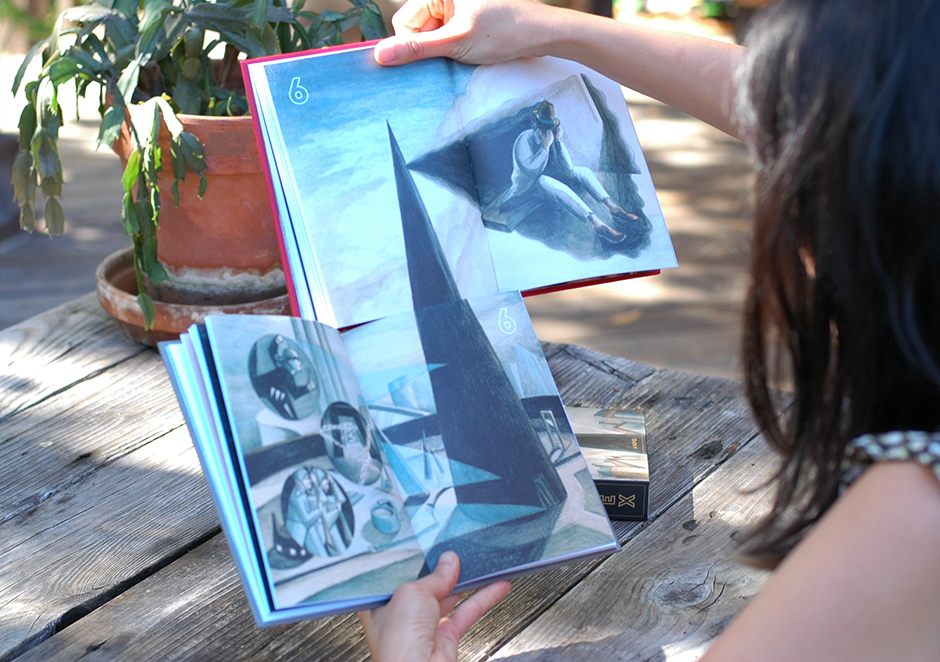

The “outside-in” two-volume hardcover edition of The Pickle Index, where images from the two volumes can be combined. (Photo: Eli Horowitz/The Pickle Index)

Ever heard of geocaching, or GPS treasure-hunting? Now think literary geocaching: stories that can only be opened in specific locations that you have to find. Hidden fictions, where you inhabit the same spaces as the characters themselves.

We all love the notion of being lost in a book—sinking deep into an armchair and immersing ourselves in words. But what about being immersed in a new way? This time, you’re walking around a story and watching it unfold not merely in your mind, but in real, physical space—sidewalks, streets, and fire hydrants, images and smells and stimuli, that exist both in the world of the story and the world around you.

Krissy Clark, founder of storieseverywhere.org, describes the experience as “a magical way of allowing you to have one foot in the physical world, and one foot in the meta-world, the annotated world on top of it.”

This is the idea behind location-based storytelling, a fledgling concept in a new realm of innovative fiction. It makes room for writing and storytelling techniques that we haven’t seen before, enabled by personalized forms of technology. Location-based storytelling adds dimension to a place, offers alternative perspectives for characters, and provides insight into people and the places that shape them.

Geolit, as one might consider calling it, is still deep in its experimental stage, and in a sense it will always be an experiment, constantly adapting to changing physical and technological landscapes.

You could curl up with a story… or go walk through one. (Photo: Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons)

Location-based lit comes in different media and forms—it can rise off a page or screen or enter through your ears, it can be narrated by one character or a town of voices, it can be realistic or fantastical, based in the past or in the future. Each form comes with its own set of rules and justifications for how and why someone would take a trip to find a story when she could grab another off a bookshelf or log into Google Earth.

The critical pioneer on this geo-literary frontier was The Silent History, an app-based archive of first-person accounts telling the story of an epidemic set in the future. Segments of the story, each its own self-contained arc, are released in the form of a serialized novel on a reader’s iPhone or iPad. The geolit component consists of “field reports”: site-specific stories that can only be opened when the reader is within feet of the report’s exact location. Field reports enhance and deepen the narrative but aren’t crucial to the plot.

They were crucial to devising the subject of the book, though; the idea of an epidemic developed out of the field report concept, since the creators wanted a storyline with widespread ripple effects. With readers also allowed to submit their own field reports, there grew to be more than 300, including one set in the White House that has yet to be opened (apparently none of the readers have gotten close enough to it).

“They offer a really distinctive, compelling, unique storytelling experience–when they are done well,” says Eli Horowitz, one of The Silent History’s creators. The goal was for people ”standing there and reading the story” to be ”combining information from the text and from the world around [them].”

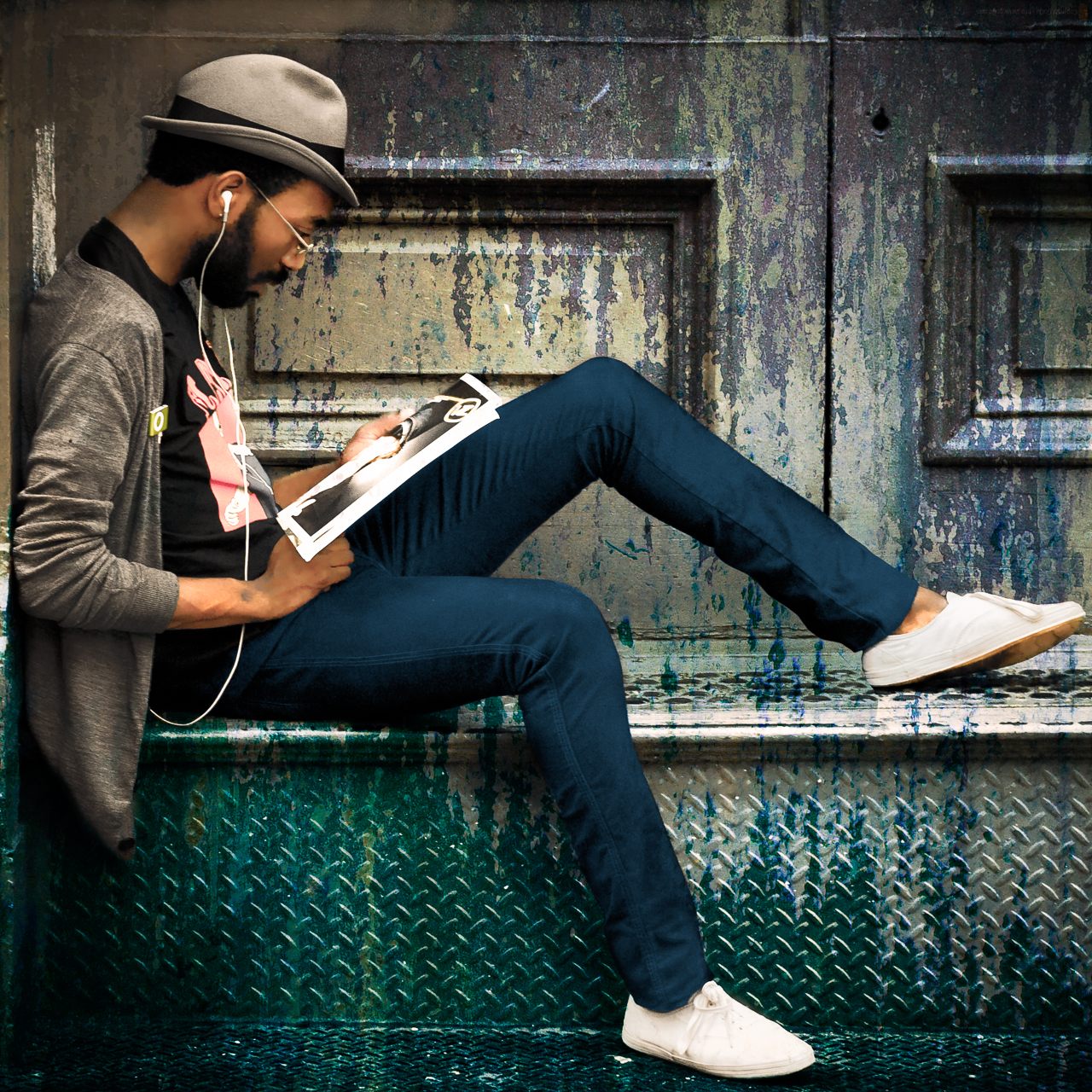

This guy could be deep in a story (or field report) taking place on that very corner… who knows? That’s geolit for ya. (Photo: debbienews/Pixabay CC0 Public Domain)

Horowitz, the former publisher of McSweeney’s and the guy who snuck a field report into the White House, sees new technologies as an opportunity for publishers to stake out a larger role for themselves rather than a diminishing one. He is frustrated by most ebooks, feeling they lack the good things about print but offer nothing in exchange.

But Horowitz isn’t interested in trends like “the next form of storytelling” or “what storytelling should be.” He says these kinds of thinking have been holding back new creative fields. “I think it gets infected with the sort of basic narrative around technology, which is the new next big thing, and the next next big thing, and what will the future look like, and what platform is going to last,” he says. “That’s not how literature is.”

His upcoming work of location-based storytelling, The Pickle Index, will come out this year in multiple forms simultaneously. Horowitz worked to design the “bookiest book possible, and the appiest app possible.” The print version features two hardcovers with illustrations that can be combined together, while the digital version will let you “enter the index itself” and experience the book “inside-out” versus “outside-in.” It’s a goofy caper about a dysfunctional circus that has to do a prison break—in some ways similar to another of his projects, The Clock Without a Face, a combination board book and treasure hunt.

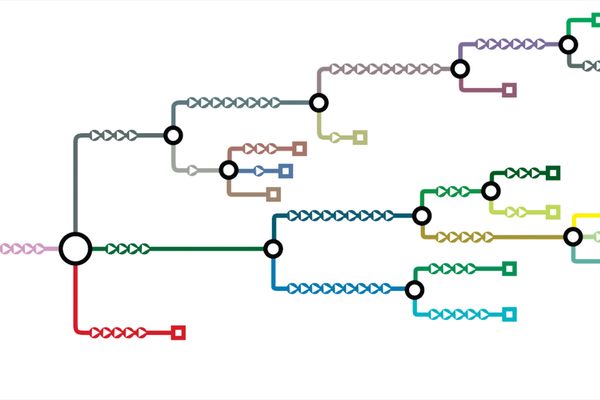

An glimpse at the “inside-out” app version of Eli Horowitz’s The Pickle Index. (Photo: Eli Horowitz/The Pickle Index)

An glimpse at the “inside-out” app version of Eli Horowitz’s The Pickle Index. (Photo: Eli Horowitz/The Pickle Index)

There’s no reason new and old media can’t coexist, emphasizes Horowitz. You can have innovation and also have nostalgia. After all, storytelling has never been a zero-sum game.

Geolit, of course, is inherently limiting. Some Silent History readers complained about being unable to participate in the geocache feature, since they lived hundreds of miles away from the nearest field report. Horowitz says he explained this to readers, but perhaps underestimated how people would actually react to the inaccessibility of his content. “There are these expectations of complete frictionlessness,” he says.

But he believes limitations are part of the experience. It’s not about going to a location to unlock content– it’s about comprehending the text by being there. “If I could get on my artistic high horse, I even sort of saw it as one of the points of the project.”

But for storytellers, it’s still a matter of trial and error. And they can’t expect the benefit of the doubt from their audience, a community currently made up of the types drawn to geocaching or ARGs, who see the existence of obstacles as part of the fun.

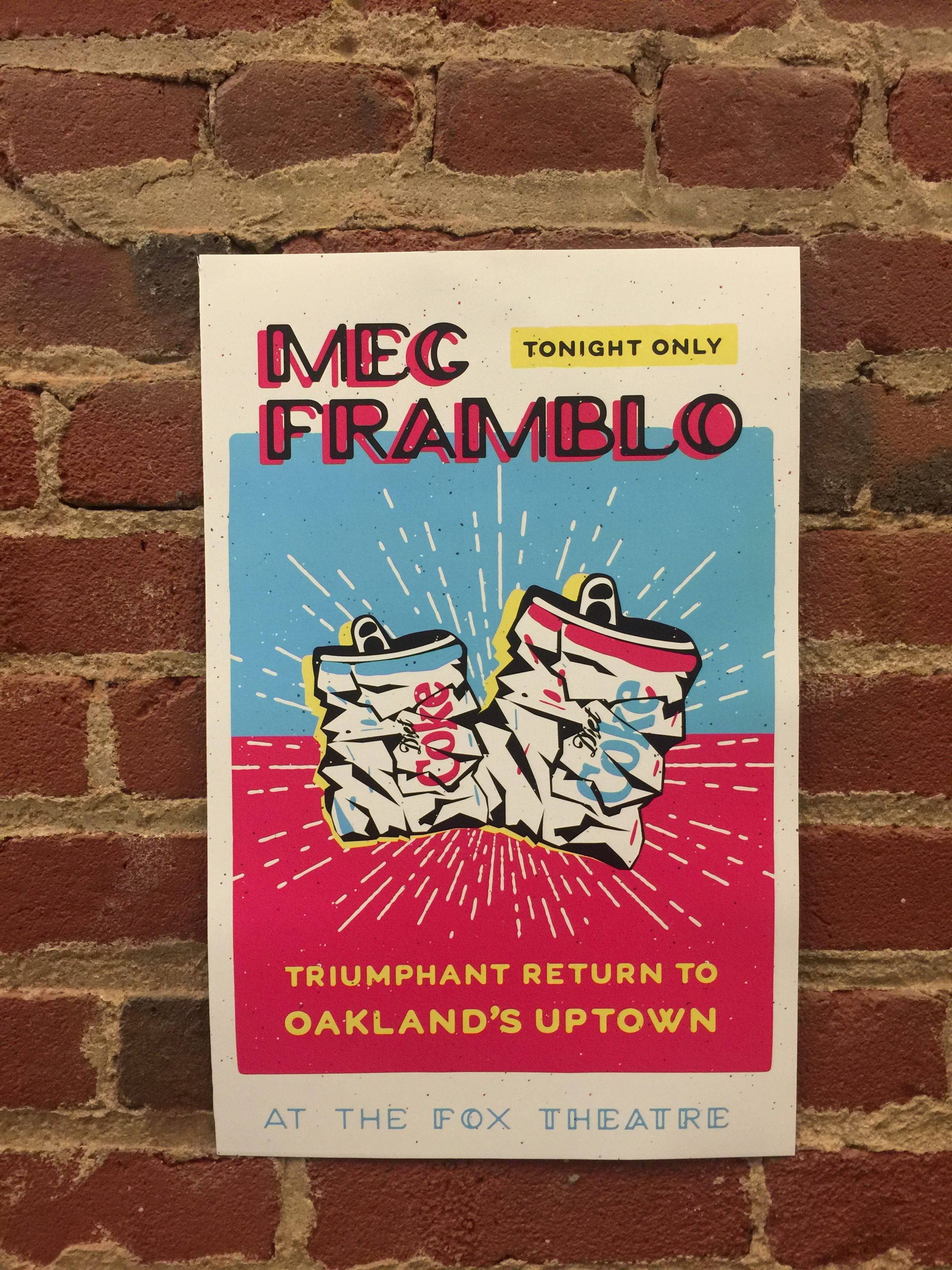

Framblo and its characters will take you down this Oakland alleyway. (Photo: Haris Butt/Detour)

“What makes for compelling stories? What are the best ways to move people around and still have them feel engaged?” These are questions geolit storytellers are trying to figure out, says Jorge Just, Senior Producer for Detour, a small San Francisco-based company that describes itself as “a brand new way to experience the world.” Detour creates location-aware audio walks, and describes itself as “the best way to experience places.” With one exception, Detour’s guides are built around narrative non-fiction, much like more conventional audio tours you may have taken in museums or historical sites—but Detour tries to tell more vivid stories.

Detour teamed up with Horowitz and podcaster Andrew Leland for the company’s first fictional audio walk, called Framblo. (You can listen to an audio preview here.) The team spent months deeply involved in developing the project, which leads story-goers through the streets of Oakland for 45 minutes; the story and characters and music they make are inextricably intertwined with the physical spaces they inhabit.

When you’re writing for place, says Just, you have to think about your audience in a different way. All writers do things to make sure that they’re bringing their readers along and challenging them appropriately, he says. But writing for a place is different from writing about a place. You’ve got to be considerate of your reader, someone you’ve asked to leave his or her comfort zone to experience your story.

“In location-based storytelling, what it means to keep your reader in mind is different, and more expanded, and much more critical,” he says. “You’ve got to let them know they’re being taken care of, give them guidance in a way that doesn’t take them out of the story, and lessen their anxiety so they can immerse themselves fully in the experience,” he says.

A visual detail on the streets of Oakland that confuses real and fictional worlds. (Photo: Haris Butt/Detour)

If a writer builds a fictional world out of words, she can sit in the corner of a coffee shop, just like her readers. But if she writes with the intention of her readers exploring through her words, she needs to be constantly on her feet, tracing out the steps of her characters, choosing which turns they take and what around them they notice.

How would Hemingway have written The Sun Also Rises if he’d expected us to be walking around with Jake Barnes in Pamplona? How about J.D. Salinger when describing Holden Caulfield’s New York angst in The Catcher in the Rye? Imagine hearing Holden’s voice as you walk through Grand Central or stop by the rink at Rockefeller Center.

Form and content should be shaping each other more, says Horowitz. Nothing is just structure or storytelling; stories should be engaged on many levels to give them an organic reality. There shouldn’t be just one reason, but instead several reasons why a piece of geolit is the way it is.

Creative minds like Horowitz and Just are already mulling through the challenges and concerns of these new modes of storytelling. If you’re reading off a device, you end up “squirrel nutting,” so buried in your gadget that you’re not looking at the world. On the other hand, earbuds can block out the people and soundscapes that give color to a place. And no one wants a swarm of 50 people, either squirrel nutting or plugged into headphones, stomping through a quiet neighborhood. But that’s still a ways away.

Is this man listening to music and reading a magazine, or is he deep in a story and examining a clue? (Photo: Joel Bedford/flickr)

Geofiction’s frontiers are constantly shifting. At the moment, Just is interested in creating ways for the people and locations to engage with each other. For example, a story might take a reader to a park, where she snaps a photograph, which then gets sent to the next stop, where it’s automatically turned into a vector image and 3D-printed. Meanwhile Horowitz is pondering stories with dynamic elements that can change depending on who is reading, or where and when they’re doing it—field reports that find you, in other words.

You’ve likely heard of literary pilgrimages, but those are afterthoughts. If geolit went mainstream, it could tap into existing communities and add chapters to established books, fan-fiction style. “As more successful place-based fiction happens, and it becomes more experimental, I think that [geolit] will become a thing—it’s inevitable,” says Just.

Right now, people are still yearning to engage with the world around them more deeply. “You know, the real world is still a real thing, no matter the time we spend in an online or virtual environment,” says Horowitz. “Certain experiences you have to immerse yourself in to really have, and to really understand.”

Imagine an afternoon in Boston or Beijing or Barcelona wandering down alleyways, looking up and down and around at details you wouldn’t otherwise have noticed, inhabiting new characters or sensing them in the surrounding spaces. Time to find yourself a story.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook