The Man Behind Herman Munster Wrote Some Puntastic Children’s Books

Fred Gwynne left a wonderfully goofy literary legacy.

Fred Gwynne, who stretched an imposing 6 foot 5 when fully grown, was never destined to be normal. Born in New York City in 1926, Gwynne had one early, consuming ambition.

“The thing I always wanted to be, ever since I can remember, is a portrait painter,” he told a New York Times reporter in 1978. And while Gwynne would—eventually—become a successful artist, it was not what he would be famous for. With a long face, a jaw like a backhoe shovel, broad mouth and expressive eyebrows, his distinctive mug and deep voice secured him a place on the Broadway stage and in Hollywood—most notably as the Frankenstein-ish patriarch, Herman Munster, of The Munsters, the CBS sitcom that chronicled the misadventures of a family of friendly ghouls from 1964 to 1966.

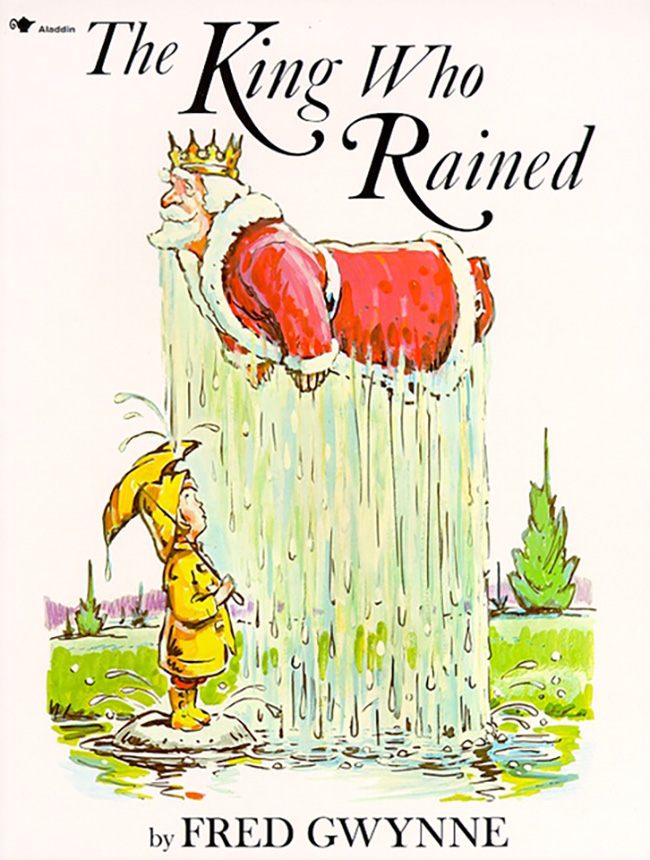

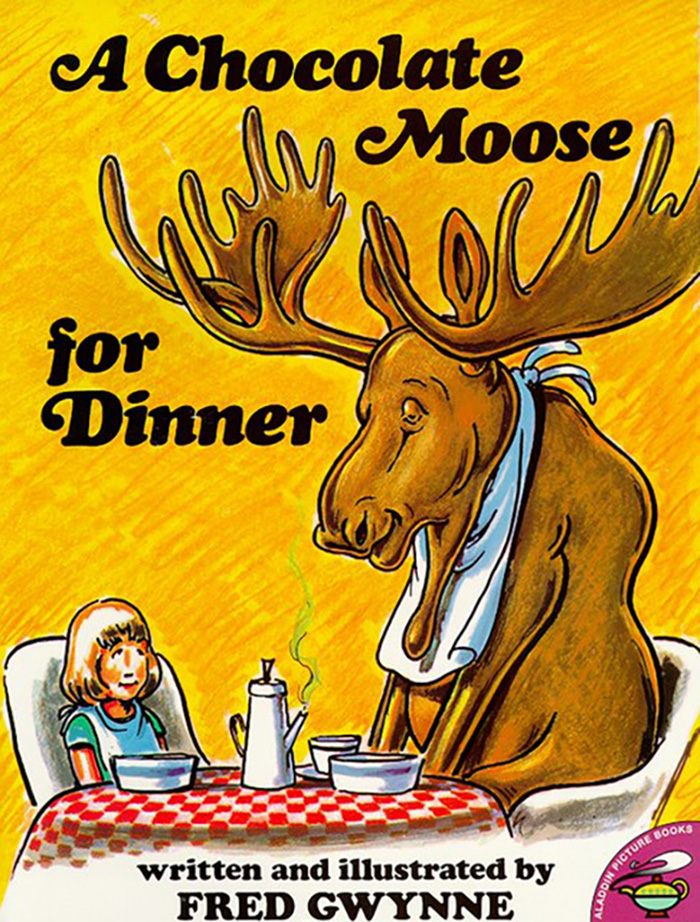

But while Gwynne racked up reviews of his eclectic stage and screen credits over a decades-long career, he was also getting notices of another, less buzzy, nature. He was writing and illustrating children’s books—really good ones. His two best-known titles, The King Who Rained and A Chocolate Moose for Dinner, attested to his love for puns and homonyms. They are those rare children’s tomes that are both goofy and sly, respecting the intelligence of children befuddled by the inanities of language. Well-loved by critics, they were also wildly popular, scoring positions on the bestseller list when published and still in print today.

Gwynne’s path to acting was circuitous. After high school he joined the Navy and served during World War II as a radioman on a submarine chaser. When his service ended, he enrolled in art school but left to attend Harvard, where he drew cartoons for the Harvard Lampoon, sang in an a capella group and acted with the Hasty Pudding Theatricals, a student troupe. He graduated from Harvard in 1951 and landed his first Broadway role a year later, in a comedy called “Mrs. McThing”. (His own alma-mater’s paper, The Harvard Crimson, declared that, while “amusing” the “plot isn’t much to speak of”.) It wasn’t exactly a speedy ascent.

After that, offers were infrequent and he became an advertising copywriter, acting when roles came along. (One of those was a supporting part in On the Waterfront with Marlon Brando.) Persistence paid off; his stage appearances led to a television offer. He became the star of Car 54, Where Are You? in which he played one half of a pair of mismatched New York City cops in the Bronx. After that show ended in 1963, Gwynne landed the role that would define him for the rest of his life: Herman Munster on The Munsters. A review in the New York Times declared that “there is not the slightest question that Mr. Gwynne superbly made up as Frankenstein, is the whole show. His shy and modest demeanor as one who yearns only to be a good neighbor sets the tone for all the other doings…”

That superb makeup included a face of paint, neck bolts, and garish forehead scar. According to gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, “It takes him 2.5 hours to put on that monstrous make-up which he does three or four days a week. He’s too exhausted after that to make many guest appearances on other shows.” A buddy told the Crimson he suspected it was the extensive costuming that in later years made it difficult for Gwynne to turn his head.

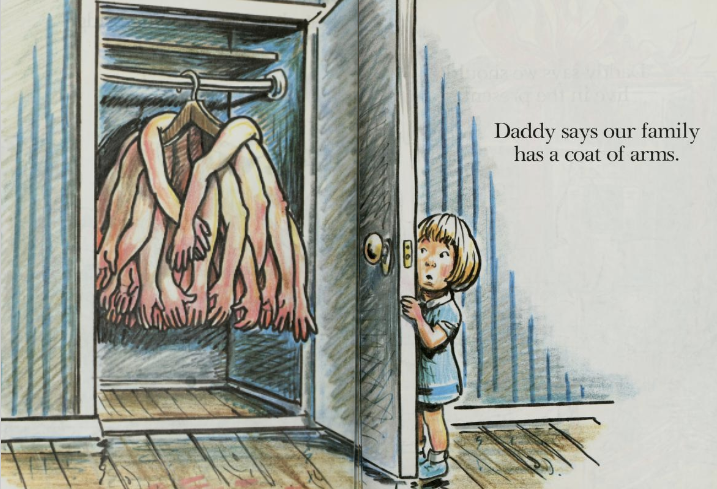

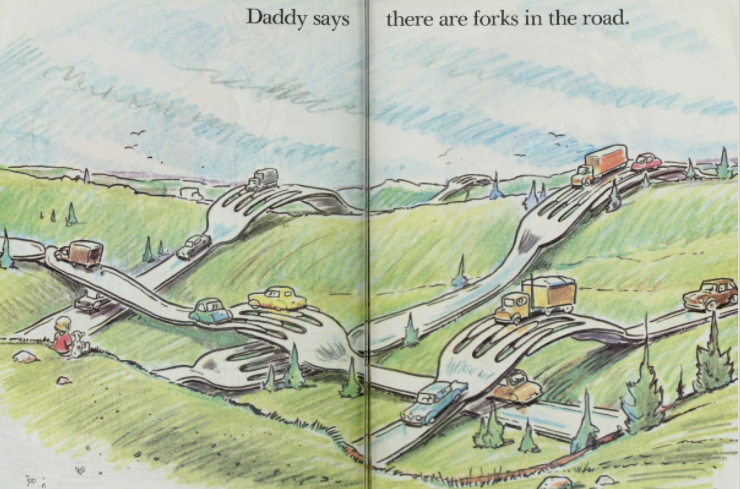

As his acting career took off, Gwynne continued to make art, sculpting and painting. He published his first children’s book, Best in Show, (about a girl who enters her dog in a contest where all the dogs look like their owners) in 1958. It would be republished several years later as Easy to See Why, the title by which it is most commonly known. Gwynne’s career as an author and illustrator began in earnest in the 1970s, during which he published several books included The King Who Rained and A Chocolate Moose for Dinner. Their pages offered up statements such as “Daddy says there are forks in the road.”, and an illustration of rolling hills overlaid with massive forks upon which the traffic drives. Gwynne’s illustrations are richly detailed and saturated in color.

“I love making puns,” Gwynne told a reporter for the Knight-Ridder Tribune News Service in 1989. He supported this statement by showing her a brass sculpture of a banana he had made, which rang like a bell when he shook it. “Banana Peal,” he said “laughing his great, deep laugh.” During the same visit he showed the writer another object of his—a clear, lucite Sherman tank with a model of a fish inside; a “Fish Tank”. The article was written on occasion of his first art show, “Drawn and Quartered: Wordplays in Oils, Bronze and Others” at a gallery in New York.

More pun books followed in the ‘80s and ‘90s, and even a fairy tale-ish story about a frog who was seeking a princess to kiss. It was called Pondlarker, and Publishers Weekly effused that its “sumptuously detailed watercolors are imbued with a stateliness appropriate to the grandeur of Gwynne’s tongue-in-cheek gravity.”

Children’s books by celebrities have become de rigueur over the decades. A modest list of stars who have penned titles for kids includes Brigitte Bardot*, Dolly Parton, Whoopi Goldberg, LeAnn Rimes, Will Smith, John Travolta, the Duchess of York (aka “Fergie”), LL Cool J, Jerry Seinfeld and Jamie Lee Curtis. The results are mixed bag; some titles have been praised, others seem to be nothing more than a bid for parents’ dollars. Gwynne’s books are the real deal.

“For a lot of years now, they are among our bestselling children’s books,” John Sargent, former publisher of Simon & Schuster’s children’s division, told Publisher’s Weekly in 1990, explaining that they routinely sold 20,000-25,000 copies a year. Another publisher agreed that they didn’t think the appeal of the books “has anything to with him as an actor”. Some education experts have even recommended Gwynne’s books as a tool for helping students to better comprehend the English language.

Gwynne continued to act on stage and in films long after his role as Herman Munster ended. Among his notable credits are Jud Crandall in Pet Semetary, who makes the unfortunate choice to introduce his grieving neighbor to the cursed eponymous location, and as the droll judge in My Cousin Vinny who inquires of Joe Pesci’s Vinny Gambini, “What is a ‘yute’?”

Gwynne died of pancreatic cancer at the age of 66 in 1993. The illness doesn’t seem to have thwarted his creative endeavors—he managed to patent a new kind of swim flipper that year, that “reduces effort by a scuba diver, thus enabling increased bottom time”.

Gwynne had a complicated relationship with Herman Munster. He felt typecast after the show ended, and indeed, when it came time to pen obituaries, most publications lingered on his TV career, with his children’s books garnering a few lines. But ultimately, he didn’t regret the job. In the same article in which he told the New York Times he always longed to be an artist, he also reflected on his most famous role and concluded, “…it was great fun to be as much of a household product as something like Rinso. I almost wish I could do it all over again.”

*Correction: We originally spelled Brigitte Bardot’s name wrong. We apologize to Ms. Bardot, icon of many realms including fashion and cinema.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook