How a Tiny Hamlet’s Wondrous Tapestry Preserves a Complex Past

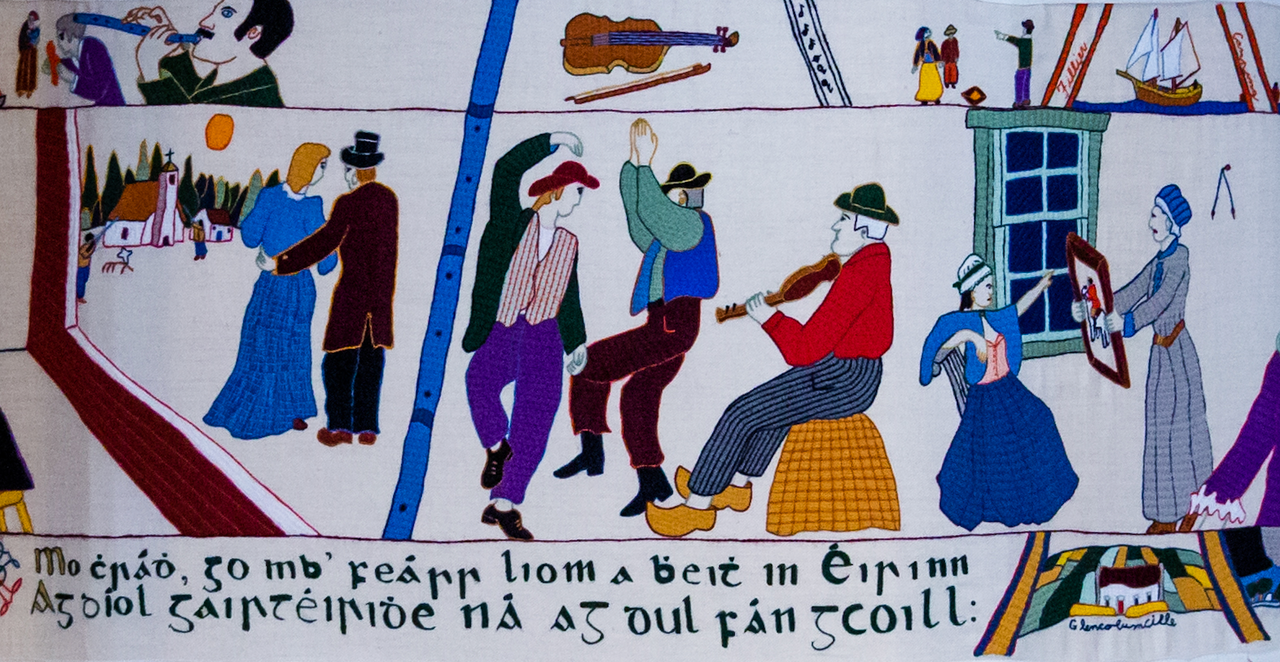

Inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry, artists and embroiderers in a Newfoundland village commemorated a lost way of life.

No matter where you’re coming from, it takes a long time to get to Conche. Drive up the Viking Trail, a windswept coastal highway, turn right at a random corner on the edge of a ragged forest, and make your way across the entire breadth of Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula. Continue to the end of the road, looping down toward this tiny fishing village—population, 170—that feels like it’s sitting right at the edge of the world. There, among the multicolored homes and longline boats bobbing at the docks, you’ll find the French Shore Tapestry, a handmade, 227-foot artwork based on a 900-year-old masterpiece on the far side of the Atlantic.

Back in 2004, artists Jean Claude and Christina Roy were leading a series of workshops in the area. For half a century, Jean Claude Roy has divided his time between his home country of France and the Canadian island, which has inspired much of his work—his bold, Expressionist paintings feature hundreds of communities in both Newfoundland and neighboring Labrador. Christina Roy, a native of Newfoundland and doctor by training, is also a skilled embroiderer who often collaborates with her husband.

At the time of the workshop, Christina was working on an embroidery inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. “She opened a bottle of wine, and by the time it was gone, we had a plan to do a tapestry based on the history of Newfoundland and Labrador,” says Joan Simmonds, the project’s co-director. Soon, they narrowed the focus: Their creation would center on the French Shore.

For centuries, fishermen from Brittany crossed the Atlantic to haul in the region’s rich stocks of cod, leaving their legacy along the northern and western reaches of Newfoundland. Along the French Shore today, you’ll rarely hear any French spoken; aside from Gallic place names, such as Port au Choix and Saint Lunaire-Griquet, much of the Breton influence has faded. In the tapestry on display in Conche, however, the area’s French connections remain vivid, including its complex history of fishing rights. The tapestry depicts the Treaty of Utrecht, which awarded coastal rights to the French in 1713, for example, while the Entente Cordiale—a wide-ranging package of agreements intended to stabilize Anglo-French relations in 1904—has a whole panel to itself.

The process of recording the French Shore’s history in thread also involved both sides of the Atlantic. The Roys returned to France, where Jean Claude drew the images for each individual panel for Christina to photograph and email back to Newfoundland. In Conche, a team of about a dozen embroiderers then stitched Roy’s vision onto cloth. “It took about three years for us to finish,” remembers Simmonds.

The exquisite work now lives in its own interpretation center, where it winds through a large room, each panel bursting with color and busy with action.

The tapestry follows a straight chronology, from the Mi’kmaq and other Indigenous people who have lived on the island for millennia, to the arrival of the Vikings, followed by the Basque, English, and French. A panel featuring a beaver and shaggy black Newfoundland dog shaking paws marks the confederation of Newfoundland with Canada in 1949, an event that, even today, doesn’t sit well with some locals.

Despite the tapestry’s broad scope, the stories it tells are often intensely personal. One panel commemorates four men who drowned after venturing out in a boat to find a priest for a woman dying in childbirth. Another marks the controversial resettlement of seven local communities from “outport” villages that the government deemed too remote in the 1960s. “They were wiped from the face of the earth,” Simmonds says of the outports, shaking her head.

Other panels illustrate the aftermath of another watershed moment in Newfoundland’s history: the cod moratorium, declared on July 2, 1992. In response to the collapse of the region’s world-famous fishery, the Canadian government shut down all commercial cod fishing. “It completely changed our way of life,” remembers Simmonds, pointing to a melancholy panel that includes a small quote: “She’s gone, boys.”

The final panel features an outline of each embroiderer’s hand, and their names, in bright threads. The hands circle a declaration that reflects the no-nonsense resilience of the people of the French Shore: “What we have stitched, we have stitched.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook