From Pony Express to Amazon Drone: The Strange History of Delivering Packages

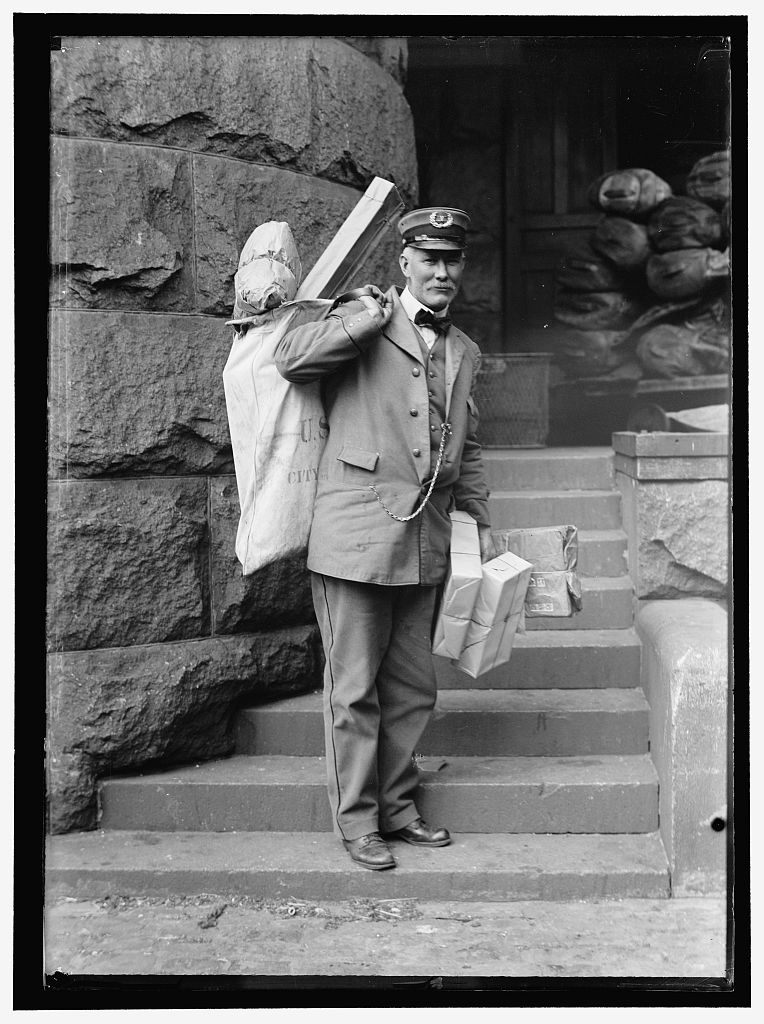

Rural Free Delivery, 1914. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Rural Free Delivery, 1914. (Photo: Library of Congress)

These days, with maps that tell you exactly when a bus is coming and weather apps that notify you exactly 12 minutes before it will start raining, the package delivery industry would seemingly have figured out how to pinpoint when your Amazon order will arrive.

And yet, no. The delivery window is still between 8 a.m.- 8 p.m., sometime the middle of Monday and Friday. And if you should happen to miss that, well, there’s always the orange note stuck to your neighbor’s mailbox.

For the past 40 years, the package delivery system has seemingly not changed; we’re still dominated by a few huge companies (some private, some public) which have storefronts and deliver products by air, land, and sea. But new advances and ideas are beginning to transform the way items are moved between consumer and producer: drones, automation, the sharing economy, megamerchants. Amazon wants you, in the near future, to hammer on a dedicated button next to your toilet that will send a humanoid or robotic courier to your bathroom with a new roll of toilet paper.

One thing that never seems to change is that Americans want stuff shipped. And shipped fast.

An 1860 advertisement for the Pony Express. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

An 1860 advertisement for the Pony Express. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Prior to the mid-1800s, package (or parcel) services were ad-hoc and unorganized both in the U.S. and in Europe. If you wanted to ship something, you’d pay a courier to do it, and the courier would, typically, drop off the package at some kind of central ground, like a coffee shop or a tavern, according to a U.S. Treasury paper on the subject from 2003.

Organization in the U.S. came with the California Gold Rush in the 1860s. All of a sudden, large numbers of Americans began to settle in California, far from most established population centers. The immense distances separating the Pacific coast from the rest of the country made the ad-hoc courier system wholly inadequate; only at scale would delivery of mail and packages make any kind of economic sense.

Thus sprang up the Pony Express, which primarily dealt with letters, and Wells Fargo, which specialized in packages.

Wells Fargo was not a bank, but a concerted effort by a bunch of New Yorkers to corner the market on all shipping, coast to coast. In the early decades of the 1800s, there were quite a few East Coast shipping proto-magnates who saw the need, in an enormous country, to move goods back and forth reliably. One of those was Henry Wells. Another was William G. Fargo. And one final one was John Butterfield. Each had their own small package delivery company, making up three of the biggest of what was at the time called the “express industry.” The three joined forces in 1850 and formed…haha, you thought I was going to say Wells Fargo, didn’t you? Nope. They created American Express.

In 1852, the American Express guys finally decided to act on the need for a West Coast operation, delivering from East Coast hubs to the new city of San Francisco and thereabouts. American Express’s board wasn’t too enthusiastic about jumping into the California game, so Wells and Fargo decided to start, basically, a moonlighting company to service the west. Wells Fargo was born, launching with 12 offices in California.

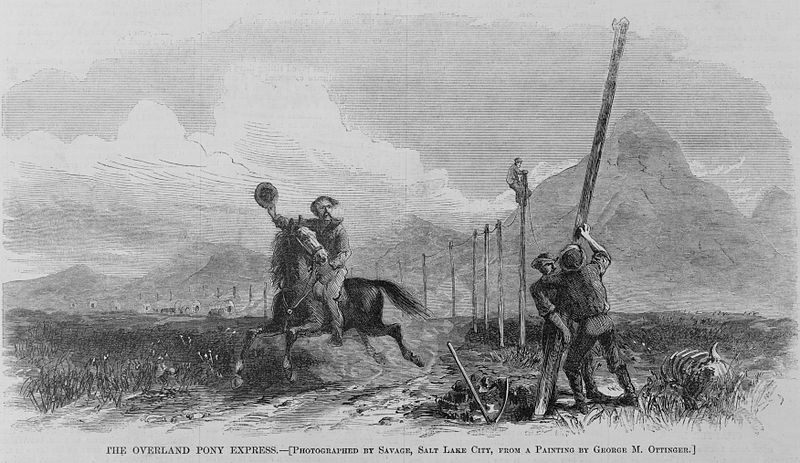

An 1857 illustration of the Overland Pony Express. (Photo: Library of Congress)

An 1857 illustration of the Overland Pony Express. (Photo: Library of Congress)

This new delivery concern very cleverly started including newspapers, for free, along with their packages. This endeared them to the news media, for one, but also to anyone who used the service. Everyone loves a freebie, and apparently people at the time also loved the news. The company also delivered gold as well, turning the company into not just a delivery service but something closer to finance and business. (At this time, it took five days for news of Lincoln’s election to reach California (and even that fast was considered an impressive achievement), which really puts in perspective the frustration of having to spend a whole day at home waiting for an Amazon delivery.)

Wells Fargo very quickly became an indispensable element of life in the West. When gold was found in a new area and a town was quickly erected, the first shops to open were a saloon, a gambling table, and a Wells Fargo outpost. It was, famously, immortalized in song in the musical “The Music Man”:

O-ho the Wells Fargo Wagon is a-comin’ down the street, Oh please let it be for me! O-ho the Wells Fargo Wagon is a-comin’ down the street, I wish, I wish I knew what it could be!

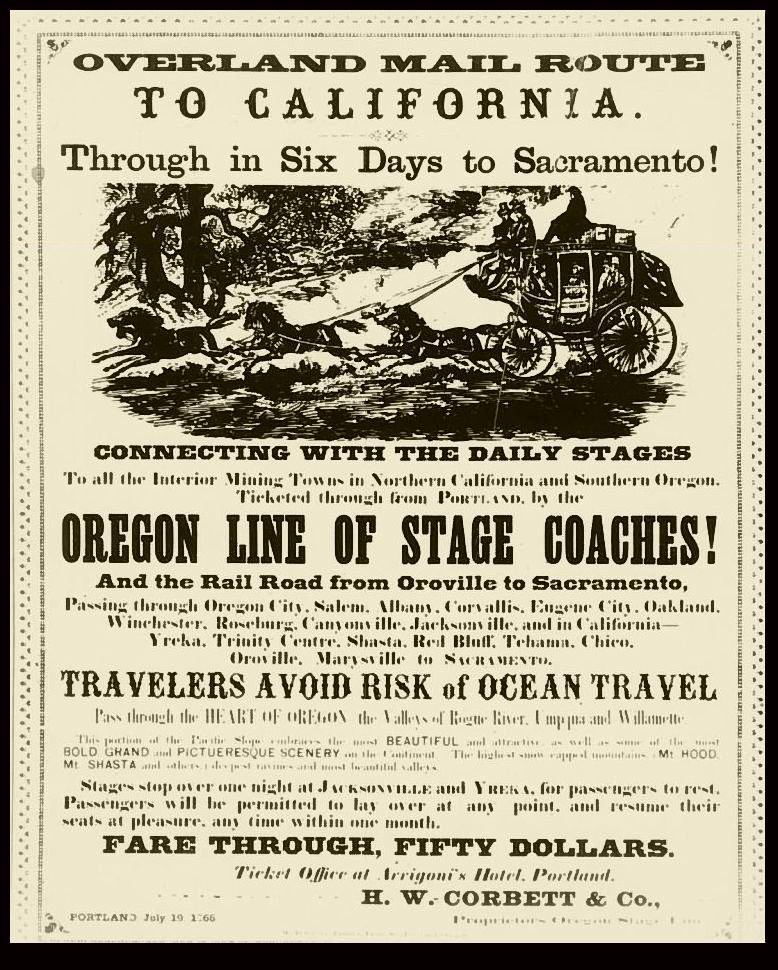

Advertising Poster for Butterfield Overland Mail route, 1865. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Advertising Poster for Butterfield Overland Mail route, 1865. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The early days of Wells Fargo were still run by the old systems: steamships down to Panama, horses over the Isthmus of Panama (a horrible trip), then ships again up the Pacific coast. It took until 1858 for the first over-land delivery service to be accomplished, which was when Congress authorized a bidding for the rights to create a mail route from St. Louis to San Francisco. The bidding was won by the not very creatively named Overland Mail Company, which was headed by John Butterfield and consisted of a partnership between American Express, Wells Fargo, and a couple other express companies.

It took 24 days to hammer out a trail from St. Louis to San Francisco, a 2,800-mile journey. Overland Mail Company secured a contract from the government to carry all official mail. The contract stated that mail would take no longer than 25 days to be delivered, but the specifics could (and did) vary; you never really knew when the mail would arrive. It was rugged country in the West, with plenty of ways to die.

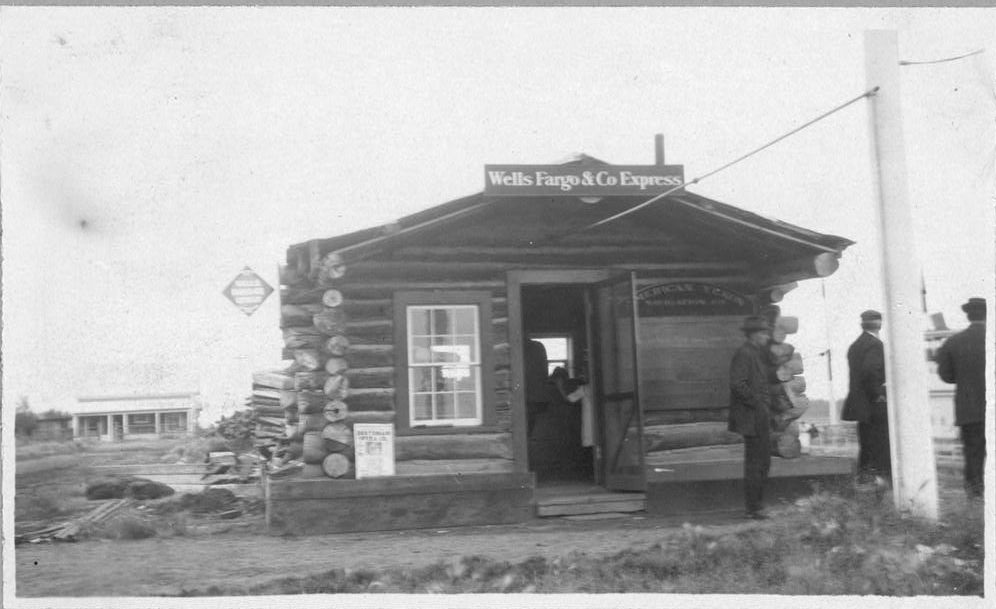

Wells Fargo & Co. Express, Alaska, 1900. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Wells Fargo & Co. Express, Alaska, 1900. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Wells Fargo, thanks to the resignation of Butterfield, took over control of Overland Mail’s board in 1860 and formally acquired the company in 1866. Also in 1866, Wells Fargo bought its biggest rival, Russell, Majors & Waddell. In between, it also acquired Pony Express and the government contract previously awarded to Overland.

But in 1869, everything changed: the country had several disparate railroad systems, controlled by private companies, and that year they were finally joined, forming the first transcontinental railroad system. All of Wells Fargo’s carefully constructed monopolies became, instantly, outdated. The owners of the Central Pacific railroad created an express company solely for the purpose of screwing with Wells Fargo, which bit, and bought the express company for the purposes of being able to use the Central Pacific railroad. Suddenly, packages would arrive in mere days, not weeks, and the company could ship much more cheaply and reliably.

A parcel post delivery man, 1914. (Photo: Library of Congress)

A parcel post delivery man, 1914. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Wells Fargo continued dominating the package delivery industry until World War I, when the railroads (and the express services which used them) were nationalized. The federal government forced all existing express companies to combine into one monopoly, called the Railway Express Agency, to make it easier for the government to ship weapons, people, and goods during the war efforts. The Railway Express Agency eventually crumbled due to the next technological advance (the dominance of trucks over trains), and folded in 1975. But by that point Wells Fargo had long since split its delivery business from its new and more profitable banking business.

The beginning of the 20th century brought huge changes to the package delivery system. It’s important to remember that the federal post office was kind of an upstart, more of a regulatory agency than an actual shipping company. Companies like Wells Fargo were much more popular in the West in the late 19th century. The first big change was the establishment of Rural Free Delivery in 1896, which ensured that mail would be delivered directly to Americans in rural areas (then comprising 54% of the population) for free, instead of forcing them to head to often faraway post offices. In 1913 came the second big change: Parcel Post, which allowed packages of up to 11 pounds (at first) to be shipped for very, very cheap. In fact it was so cheap that college students from the 1910s to the 1960s literally mailed their dirty laundry home to have it cleaned, because it was less expensive than having a professional clean it nearby. They had special metal laundry boxes for that. Along with laundry, an entire bank was broken down into bricks and mailed.

Parcel post area of mail room showing trucks and tables stacked with packages, U.S. Post Office, Washington, D.C, c. 1920. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Parcel post area of mail room showing trucks and tables stacked with packages, U.S. Post Office, Washington, D.C, c. 1920. (Photo: Library of Congress)

A small child was mailed, too. Charlotte May Pierstorff fit under the then-active weight limit of 50 pounds (today it’s 70) and was mailed from Grangeville to Lewiston, Idaho for 53 cpents. Her trip took only a few hours. (It’s no longer legal to do that.)

A new company, initially known as the American Messenger Company, sprung up in Seattle in 1907, just before Parcel Post debuted, founded by a teenager who wanted to use his bicycle, then motorcycle, then his Model T to deliver packages locally. It was, basically, a lemonade stand model—a bunch of kids doing odd jobs for not very much money. Those odd jobs just happened to include package delivery services.

James Casey, at 19 years old, quickly expanded the company, merging with other like-minded small courier services and moving quickly beyond the borders of Seattle. In 1919, the company changed its name, becoming the United Parcel Service, or UPS. The brown color was there from 1916, when the company started using cars—and very cleverly arranging packages and delivery routes so as to maximize efficiency.

The car and truck boom was the catalyst for UPS’s explosion, but UPS also became a direct competitor to the Parcel Post system by securing “common carrier” rights throughout the country. Common carrier rights means that UPS has some of the rights and responsibilities of a public company, though it’s private: it is explicitly working for the common good, and is subject to regulation by the government. Having those common carrier rights allowed UPS to become the largest package shipper in the world. UPS, reliant on land travel, wasn’t the first to attempt airmail; the Post Office Department, the predecessor to the USPS, took over a few planes from the Army and began delivering mail by air in 1918. But package delivery was not done in these early years and it took until the late 1920s for the first attempt, by UPS. The company promptly gave up, finding that it wasn’t cost-effective, until the 1950s, when it was resurrected thanks to cheaper flights.

In 1970, President Nixon abolished the Post Office Department and created the United States Postal Service. The USPS was designated the only carrier of official mail in the country, which restricted the private companies like UPS to either package delivery or courier-type deliveries. Regular mail was cheap and efficient done by the USPS, so UPS couldn’t really compete. But packages were something different. Enter Federal Express. Fred Smith, the company’s founder believed that the USPS’s package delivery service through the airlines was wildly inefficient, relying on governmental pressure on airlines to deliver packages, as well as communication between several different entities (a local post office, the USPS, however many airlines it took to ship a single package). His idea was to streamline the process so that only Federal Express handled everything, from receiving to delivering. After initial financial woes (the company was literally bailed out on Smith’s blackjack winnings one time), FedEx became a huge success.

The present-day hasn’t much changed from the 1970s: packages are delivered by either the USPS, UPS, FedEx, or (more rarely) any of a few regional companies. But that’s soon to change, becoming much more chaotic. Amazon, the largest shipper in the country, is experimenting with using its own private courier service for its same-day Prime Now program, as well as playing around with the idea of using drones for (very) small deliveries.

Loading air mail in Detroit in the 1930s. (Photo: Bill Whittaker/CC BY-SA 3.0 WikiCommons)

Loading air mail in Detroit in the 1930s. (Photo: Bill Whittaker/CC BY-SA 3.0 WikiCommons)

One element that deserves changing is the cursed delivery window requiring customers to be at home for an entire day, having no idea when the package will actually be delivered. UPS, FedEx, and the USPS have all been very slow to adopt smaller delivery windows. “What makes it complex is the sheer number of deliveries we make each day – we deliver about 18 million packages every day,” says Dan McMackin of UPS. Implementing tracking in each package and algorithmically figuring out when a package is likely to arrive is tricky, and these companies haven’t quite figured out how to adjust those algorithms on the fly so that shippings are grouped depending on a customer’s preference for delivery. In other words, it’s hard for the delivery service to tell you when the package will arrive, and also hard on the service if you want to tell the service when to deliver the package. Of course, money can change all of that; UPS, FedEx, and the USPS all have programs, usually crafted as a subscription, which allows the consumer to pick a delivery window. But it’s not universally free, not yet.

The sharing economy is destroying the hegemony of the UPS/USPS/FedEx system by allowing customers to hire couriers independently through services like TaskRabbit. Instead of booking through a courier service, TaskRabbit allows anyone to become a courier, instantly—without training, maybe, and without necessarily offering much protection either to the user or to the newly minted courier, but circumventing larger companies does come with a reduced price tag. This kind of thing, weirdly, works not just for local deliveries but also for giant companies like Amazon, who have “fulfillment centers” (read: giant warehouses) all over the country. A customer in Seattle and a customer in New York can both order a 48-pack of Diet Pepsi from Amazon and have it delivered the same day, because both Seattle and New York have nearby warehouses that stock Diet Pepsi. Smaller retailers can’t compete, but that system also boxes out the delivery services. Who needs ‘em?

The future of package delivery, at least in the near term, is chaotic: amateurs, machines, who knows what else. But, then, package delivery has always been chaotic.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook