The Fruitcake Prison Break That Reshaped Irish History

You’ll never guess this dessert’s key ingredient.

What may have been the most consequential fruitcake of all time was—like most fruitcakes—left uneaten. In an unlikely scheme so gimmicky that it’s now a television trope, this 1919 loaf freed one of Ireland’s most influential statesmen and helped forge a nation.

Eamon de Valera was no stranger to prison. A devout Catholic who politicized around Irish republicanism and rose quickly through the ranks of the Irish Volunteers (forerunners of the Irish Republican Army), the man known by comrades as “Dev” headed a battalion during the Easter Rising against the British in 1916. Overtaken and imprisoned, de Valera was spared execution and given a one-year sentence. (“My name was next on the list to be shot,” he told audiences in the years that followed.) General Sir John Maxwell, commander of the British forces, judged the lithe, hook-nosed former math teacher “[unlikely] to make trouble in the future.”

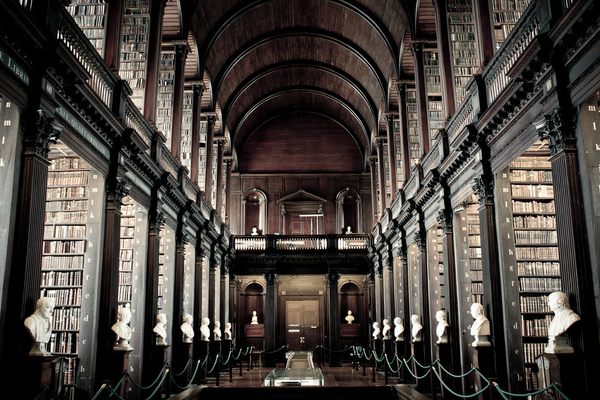

Once freed, de Valera immediately began making trouble. Aside from being elected to parliament, he led the emergent, revolutionary Sinn Fein party, toppled the long-dominant Irish Parliamentary Party in 1918 elections, published a manifesto vowing to secede, and helped form Dáil Éireann, a separatist parliament that refuted Crown rule. Making up for heinous misjudgment, the British sloppily detained de Valera and 72 fellow republicans—on later disproven allegations of conspiring with Germany—and incarcerated him in Lincoln Prison, which, in its 46-year history, had seen no escapes.

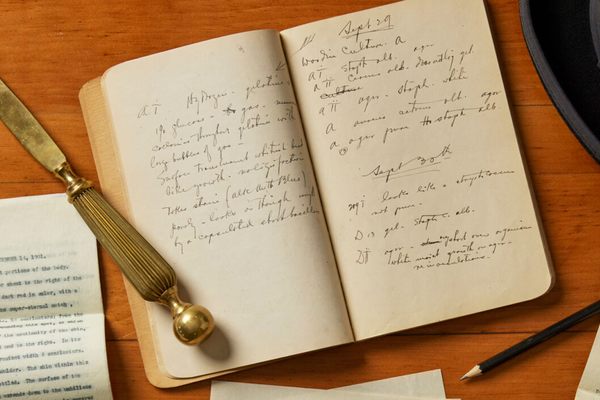

A good Catholic, he became an altar boy in the prison’s chapel and pilfered the chaplain’s master key, making impressions in handfuls of wax he had softened with his own body heat. De Valera had an artistically-inclined fellow inmate draw a Christmas postcard depicting a drunken man trying to fit a large key into a small hole—a ruse that delivered the key’s dimensions to his co-conspirators without arousing suspicion from prison-mail censors.

Weeks later, Fintan Murphy arrived at Lincoln Prison with a cake for de Valera, a replica of the postcard key baked into the corner. “The head Warder was called,” recalls IRA affiliate Liam McMahon, “who brought a very thin knife, and started prodding the cake. Fintan was in agony over the thing … but he never contacted the key and the cake [got] in.” De Valera remembers feeling “joy at having got [the key], [but] was qualified by a feeling that it was too small.” Indeed, the initial key did not fit the locks.

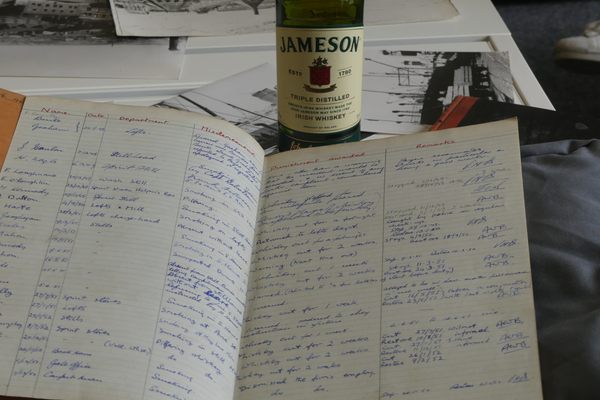

De Valera sent a more precise design embedded within an even more intricate Celtic symbol, yet upon its arrival in a second cake, found this key didn’t take either. With the cake deliveries growing increasingly suspicious, de Valera’s accomplices mailed him a blank key and a set of files within a subsequently “rather heavy … oblong fruit cake,” remembers McMahon, whose wife Susan baked the cake. Another inmate dissected a prison lock with a contraband screwdriver so as to perfectly sculpt this blank. Then, in the evening hours of February 3rd, 1919, de Valera and two comrades became the first men to escape Lincoln Prison. They walked to the still-standing Adam & Eve Tavern where a taxi whisked them to a safehouse, and then on to Dublin where de Valera was greeted with a hero’s welcome—and the presidency of Dáil Éireann.

Irish historian Diarmaid Ferriter called de Valera “a man of international significance and a role model in the 20th century struggle for small nations to challenge and defeat imperialism.” Despite backing the defeated party in the Irish Civil War, he formed the Fianna Fail party, which won parliamentary elections throughout the 1930s and 1940s, and he won the taoiseach (Prime Ministry) in 1937, 1951, and 1957, which made him the longest serving in Irish history. During his first term, de Valera amended the Irish Free State Constitution to further assert Irish sovereignty, declaring Gaelic the national language, officially recognizing the Catholic Church, extricating all roles of “the King,” and naming the sovereign state Éire, or “Ireland.” No small feat for an oblong fruit-cake.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook