What Was the Point of Elevator Music?

Contrary to popular belief, it wasn’t because lifts were terrifying.

It takes the Empire State Building’s marble-lined elevator approximately one minute to travel almost 1,000 feet up to its 80th floor, where visitors can peruse an exhibit of the building’s history before their final ascent to the observation deck on the 86th floor. The elevator is so fast the electronic numbers whizz by quicker than the display on a stopwatch. But it feels even faster: On the ceiling, an animated display shows the elevator rising at perilous speeds through a whirl of activity—cranes, construction, sitting men balanced perilously on a beam.

When the building opened in 1931, the journey took a little longer. But there was a different distraction to while away the seconds: canned music played throughout its elevators, lobbies, and observatories. Rather than bossa nova or cheesy “elevator music” themes, this was likely simple classical music—a 1945 New York Times article about the Army B-25 bomber that crashed into the Empire State Building’s 79th floor described a scene of chaos against “the soothing sounds of a waltz.”

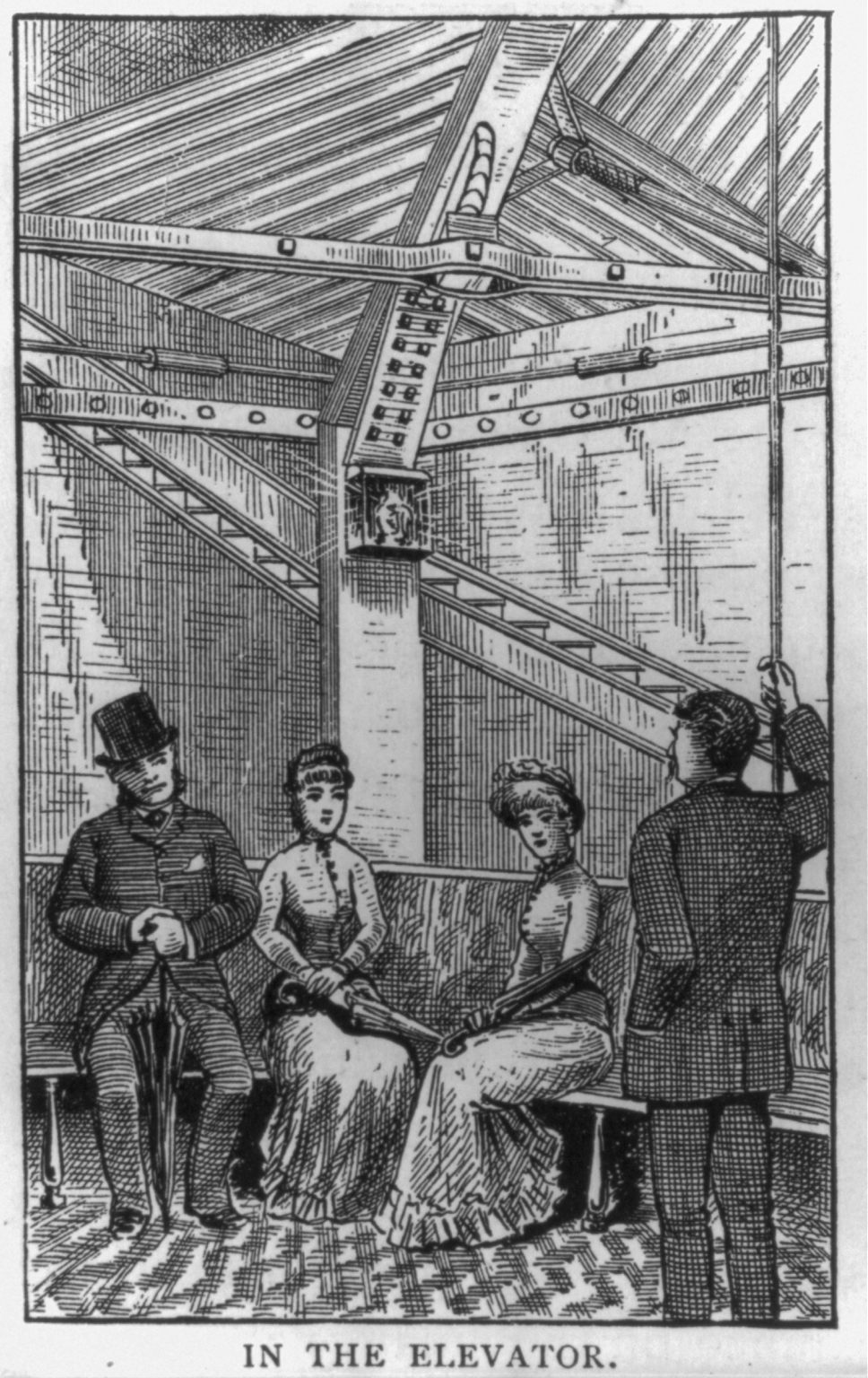

Why was this waltz there at all? The most popular theory about the origins of music on elevators, repeated everywhere from the New Yorker to the writer Joseph Lanza’s history of Muzak, is that elevators were terrifying, and people needed the music to calm their frazzled nerves. As Lanza writes: “Next to roller coasters and airplanes, elevators were perceived by many as floating domiciles of disequilibrium, inciting thoughts of motion sickness and snapping capables.” Gentle background music, he suggests, helped to minimize that terror, particularly after these conveyors were automated in the 1920s. Attendants stopped being a standard feature, and people were left alone in the box. Only music could help take their minds off the experience.

Yet on closer interrogation, there are a few holes in this explanation. The earliest known references to music in elevators are from the early 1930s—the same time the Empire State Building opened its doors. By then, people had been riding elevators for decades. Fully automated elevators, which did not require attendants, had been around since 1918. And as early as January 1886, around 30 years after Elisha Otis invented the modern elevator, the New York Times observed: “The many lofty buildings which have been completed in New-York during the past year have brought into great prominence the passenger elevator as an indispensable means of transit and the security of this class of labor.” Were people really afraid of elevators nearly 80 years after they were invented?

“I don’t think elevator music was really designed to soothe the raging beast,” says Patrick Carrajat. (Carrajat is the go-to guy on all things elevators: The former chief executive of an elevator parts business, he is also the author of The History of the Elevator Industry in America 1850-2001 and founder of the erstwhile Elevator Historical Society.) Instead, he says, elevator music was there as a distraction to fend off boredom and keep people’s minds off the interminably long time it took to get from floor to floor.

By the 1930s and 1940s, when music first became common in many high-end elevators, elevators themselves were already quite smooth—not the jolting deathtrap Lanza suggests. Certainly they were sufficiently quiet that elevator music, which was always “pretty nondescript,” says Carrajat, could easily be heard. At first, in other elevators as in the Empire State Building, it was gentle, instrumental music. In 1934, Muzak released its first recording—as the years went by, and the service gained popularity, their cruisey tunes, which have been parodied in thousands of television programs and films since, became the standard. Elevators were boring, not scary, and music helped take your mind off that fact.

That’s not to say that no one was ever afraid of an elevator, as indeed they were of early escalators. In the very, very early days, they probably did seem terrifying, or at least mildly perturbing.

At the 1853 World’s Fair, in New York, the entrepreneur and inventor Elisha Otis made his original “elevator pitch.” This included a death-defying drop, in which he “dramatically cut the only rope suspending the platform on which he was standing,” according to Otis Elevator Company lore. “The platform dropped a few inches, but then came to a stop. His revolutionary new safety brake had worked, stopping the platform from crashing to the ground. ‘All safe, gentlemen!’ the man proclaimed.” The display raised eyebrows—and although elevators were adopted enthusiastically, with 2,000 Otis elevators in use within 16 years, it must have taken a while for people to come to terms with the fact that they were not, in fact, in free fall.

But accounts of the Empire State Building’s opening don’t focus on any such terror. Instead, journalists were most interested in how many elevators there were and how they worked simultaneously. A Popular Science feature from the time describes 58 elevators with “automatic starting, stopping, level-ing, and door opening and closing devices,” and an additional nine “with various degrees of self-operation” for the top seven stories. The installation of these 60-odd elevators cost an eye-watering $4 million, the magazine reported, or around $65 million in today’s money.

Even then, elevators were extremely safe. If one of the six cables supporting the Empire State Building’s elevators snapped, the Popular Science journalist wrote, “the safety of the car would not be interfered with.” In fact, if “one, two, three, four, or even five cables [were to] break, the car would not drop, as one cable is sufficient to carry the whole load!”

In addition to distracting people from their boredom, elevator music had a certain cachet: It revealed that a building’s administrators had extra cash to spare entertaining people in the lift. Having piped music playing in the background was seen a sign of classy refinement. Muzak became the most prominent name in background music, leaking out of the elevator and into the vestibule or even the office, where it purportedly increased workers’ productivity. Even the White House, writes Ethan Trex for Mental Floss, was susceptible to its anodyne charms: “The presidential residence was wired for Muzak in 1953 during Dwight Eisenhower’s administration. (He wasn’t the biggest presidential fan, though; Lyndon Johnson actually owned Muzak’s Austin franchise during the 1950s.)” These smooth tunes would have been played not just in the elevators, but everywhere in the building.

But in the 1960s and 1970s, people seem to have begun to find elevator music irritating. Before then, no one had used the term specifically, subbing in “piped music,” “canned music,” or simply Muzak, whether or not it was. The earliest references to the specific terms “elevator music” or “lift music” all date to around this time—and they’re mostly pretty disparaging. In 1963, the Lima News, in Ohio, described elevator music on a “monstrous” par with “airplane music” and “factory music”; in 1976, the New York Times described a restaurant’s background track as “overamplified elevator music.” (Contemporary references from across the Atlantic in the Times of London talk about “lift music” in similar tones.) Gradually, Carrajat recalls, elevator music was stripped out of low-end and high-end lifts alike as people grew disillusioned with background crooning. “I think the last time I remember hearing it was probably in the late ’60s or early ’70s,” he says—though it’s been a fixture of many, many television shows in the time since.

These days, people don’t need music in elevators to distract them—instead, we all thumb mindlessly through our smartphones. But in the interim, Carrajat recalls another way elevator companies helped to make the time pass faster.

He remembers installing an elevator in a building on New York’s swish Upper East Side. “They said, ‘Can’t we do anything to speed it up?’” Actually making the elevator faster would have been prohibitively expensive, Carrajat says, so he put a mirror above the push button station instead. “As soon as you did that, you saw people stop complaining about the waiting—because whether they were a guy or a gal, they’d come up and check their hair, the women checked their make up, et cetera,” says Carrajat, laughing. “They weren’t aware of how long they were waiting.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook