How a South American Soap Opera Created a Turkish Dessert Craze

A tres leches cake. (Photo: Hungry Dudes/flickr)

Desserts have a special place on the Turkish table—after all, this is a country whose main cultural export is Turkish Delight (lokum). But it’s not just helva country. Turkey has a long and noble pastry history, with many dessert variations, and a special knack for soaked desserts like revani (a semolina cake), soaked in a light syrup, and lokma, fried dough balls, splashed with syrup.

So when a Latin America dessert called tres leches (modified to trileçe in Turkish) began appearing on menus throughout Istanbul a few years ago, it made sense, palate-wise. What is more surprising is the source of this dish: South American soap operas.

The cake itself is a fairly simple concoction, one that is easily modified. In the Americas, tres leches is often a yellow or white cake, soaked in three different kinds of milk: evaporated milk, condensed milk, and heavy cream or whole milk. The canned products are hard to find in Turkey, so bakers use whatever they can find that tastes good – any thick and sweet dairy will work. The food blog Culinary Backstreets published a throrough look at Istanbul’s different trileçe recipes earlier this year and found different bases for the cake. It’s sometimes made of standard flour, sometimes of semolina. It’s soaked with just about any type of milk–sheep, goat, cow, or water buffalo; whipping cream, heavy cream, or whole milk; condensed or evaporated or sweetened. It is usually topped with caramel, a feature not found on the American version.

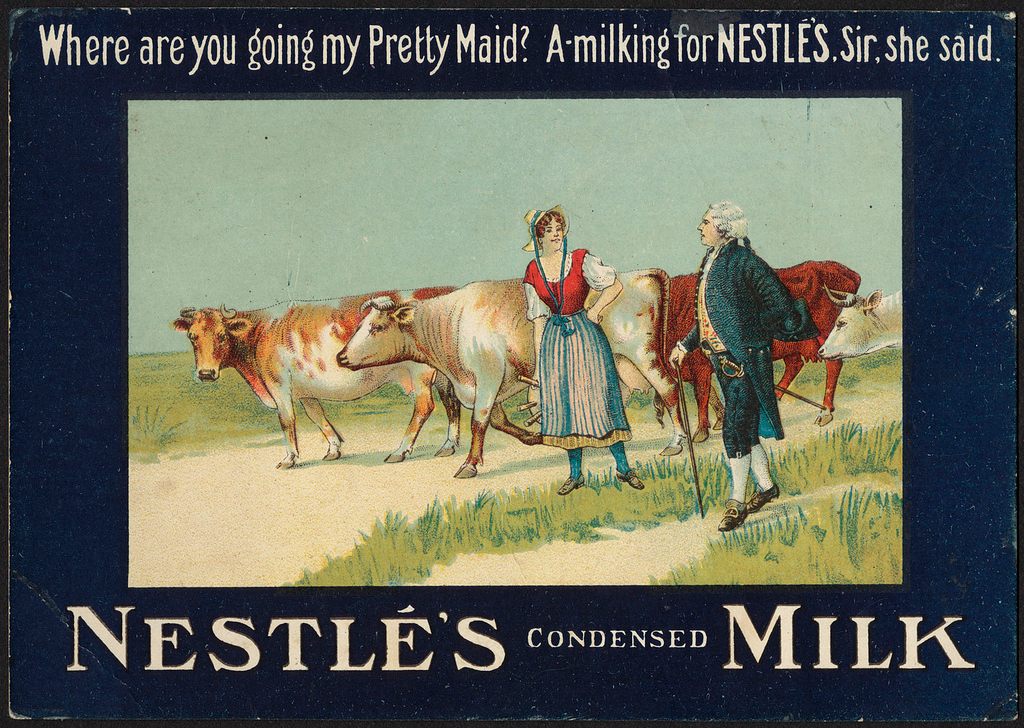

A 19th century advertisement for Nestle condensed milk. (Photo: Boston Public Library/ flickr)

Nobody really knows who invented the tres leches cake; it’s extremely common and integral to the cultures of most Latin American cultures, from Mexico to Argentina, and is even popular in Brazil, which sometimes due to linguistic differences is exempt from trends in Latin America. It’s possible it was invented by Nestle, the main producer of canned milk (including condensed and evaporated milks), which began putting a recipe for tres leches on the labels of its products in around the 1940s. It also draws from the tradition of European soaked cakes – think Italian tiramisu, which includes baked ladyfinger cakes dipped in coffee until soft, or British savarin, a cake soaked in syrup.

But we do have a guess about how tres leches became trileçe. It’s all about soap operas.

Turkish trileçe. (Photo: gorkem demir/shutterstock.com)

See, Turks are nuts about soap operas. The Wall Street Journal reported that in 2012, Turkish soap operas were worth an estimated $130 million. More importantly, Turkish soap operas, with high production values, are exported to all surrounding regions–and given Turkey’s strategic spot in the center of Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, that means an awful lot of people outside Turkey are familiar with the stars of Aşk-ı Memnu, Ayrılık, and other shows. An estimated 75 percent of people in the Arab world have seen a Turkish soap.

In fact, the Turkish hunger for soap operas is so deep and intense that even the thriving domestic industry can’t provide enough content. So foreign soaps are extremely popular in Turkey, including many from Latin America. Many sources guess that Latin American soaps, especially a few from Brazil, were responsible for introducing the tres leches to Turkey. (The Turkish newspaper Hurriyet credits Albania with first introducing the South American dessert into the region—soaps are very popular there, as well.)

Turkish baklava. (Photo: Natalie Sayin/flickr)

This isn’t as weird as it sounds. In the U.S., where we have a massive film and television industry backed by billions of dollars and full of global superstars, the quick-and-dirty world of soaps is restricted to daytime viewing. American soaps are a niche genre–a successful niche genre, sure, but a niche. American soaps have their own publications, their own airing times, their own fans; they don’t tend to break out into the culture at large. In other countries, including Turkey, Mexico, and South Korea, things couldn’t be more different.

Outside the U.S., soaps are exported around the world, traded and obsessed over, and their stars and settings become famous. The concept of “soap tourism” is a new field of sociological study, and a source of millions of tourist dollars for various governments.

Chinese viewers of the Korean soap My Love From The Star have been flocking to the spots where key scenes were filmed, including the beautiful Jangsado Island in Tongyeong. Muslim tourists from the Middle East have been heading to Turkey to see the house where the eponymous star of the Turkish soap Noor lives. South Koreans have booked flights in droves to Prague to see the beautiful city that serves as the setting for the soap Lovers In Prague.

And in little ways, the cross-pollination of cultures via soap operas is serving as its own little harbinger of globalization. In the same way that tres leches became popular in Turkey, Chinese imports of a South Korean beer featured in a popular soap have soared. But there are more serious effects as well; smuggled South Korean soap operas have long served as a window to the outside for North Koreans who have no other way to see it. They’ve often been cited as a potential spur to defection, and the North Korean government has actually killed citizens for viewing them.

Soap operas in the U.S. may seem like ephemeral bits of fluff, a low-budget, poorly written, poorly acted version of our dominant prestige entertainment industry. But elsewhere, they’re powerful forces of education and diplomacy. Or at least cake.

Update, 11/12: The story originally confused lokum with baklava. We regret the error.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook