How Novels Came to Be Written in the Voice of Coins, Stuffed Animals and Other Random Objects

Why a niche 18th century literary genre still has meaning today.

A 19th-century typewriter. (Photo: Pixabay)

The most popular novel of 1760 England was an episodic narrative of the observations of a mind-reading coin imbued with the very spirit of gold itself.

Largely forgotten today, Chrysal, or the Adventures of a Guinea thrilled contemporary readers with “Views of several striking Scenes”, an insider’s account of the scandalous doings of the “most Noted Persons in every Rank of Life”, and tales from the gold mines of Peru, the streets of London, the canals of Amsterdam, the ports of the Caribbean, and the front lines of the Great War. Despite Chrysal’s tendency to lapse into somewhat exhaustingly florid language, readers loved it—the book went through five print runs in just three years, 20 before the century was out. In 1765, author Charles Johnstone, a failed barrister who would later forge a career as a journalist in Calcutta, produced an expanded four-volume edition, also a best seller.

Though Chrysal wasn’t the first book written from the perspective of a unit of currency—The Golden Spy, written in 1709 by writer-for-hire Charles Gildon, was a collection of stories narrated by a collection of coins of various nationalities— it was a tipping point for what are frequently referred to as “it-narratives”. It-narratives, also called “novels of circulation” or “object narratives”, are novels or stories that take an inanimate object or an animal as its narrator, endowing it with a subjectivity, though not always agency. “The idea is that they’re treated as person-like,” explains Dr. Mark Blackwell, professor at the University of Hartford and editor of The Secret Life of Things: Animals, Objects and It-Narratives in 18th Century England. That definition, however, can be flexible: One writer in The Secret Life makes the compelling argument that John Cleland’s saucy Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, published in 1749, was a kind of it-narrative of an “enthusiastic vagina”.

Chrysal, or the Adventures of a Guinea, by Charles Johnstone. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

These kinds of stories—secret histories and fictional memoirs—gripped the English reading public’s imagination. Chrysal was still the gold standard, so to speak, in it-narratives, but it was a bit like the first detective novel or the first bodice-ripping romance novel: the beginning of a genre. With a market proven, writers for hire began churning them out with variable quality. By 1781, a bored reviewer in The Critical Review complained, “This mode of making up a book, and styling it the Adventures of a Cat, a Dog, a Monkey, a Hackney-coach, a Louse, a Shilling, a Rupee, or — any thing else, is grown so fashionable now, that few months pass which do not bring one of them under our inspection.” The reviewer wasn’t entirely immune to the charms of The Adventures of a Ruppee, declaring it “well imagined and not ill-told” and “better entertainment than cards and dice during the long evenings of the Christmas holydays.” The Adventures of a Hackney-coach, reviewed in the same issue, fared much worse: “This is as execrable a hack as any private gentleman would wish to be drove in; being nothing but a heap of uninteresting, ill-written adventures, in a pompous and turgid style.”

“You sort of read these and you think, ‘This is one version of 18th century writing as a career,’” says Blackwell, noting that the novels were often penned by “hack writers”, writers for hire. “It’s a sort of para-literary form, a certain kind of junk fiction in a way.”

A George III gold guinea, from 1789. (Photo: Public Domain)

But consumable junk fiction was a somewhat new thing in the 18th century, just as the novel itself was a somewhat new thing. When the novel as a literary form was born is a matter of debate; the lineage of the modern novel spiderwebs through the past 2,000 years of history, linking Greek and Roman prose narratives and Japanese tales, experimental philosophical stories of Islamic Spain and heroic romances of medieval England and France.

But in the 17th and 18th century, the novel was increasingly becoming a vehicle for telling a story grounded in how real people would react to real situations. And as the it-narratives exemplify, there was a lot of experimentation in how that vehicle rolled.

The rather dull-sounding The Adventures of the Pin-Cushion. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

“They’re trying to figure out new ways of writing narratives,” says Blackwell, describing the it-narrative as a “narrative gimmick”. And it was useful: Like contemporary fictional accounts of humans, including Moll Flanders and Tom Jones, it-narratives offered writers a way of giving their readers access to stories from different social classes, or typically hidden professions, or other countries.

But crucially, unlike those human memoirs, it-narratives allowed writers to do that divorced from a potentially complicated human perspective. Satirical, snarky commentary on contemporary political or social situations ruled early versions of the form; some, against the backdrop of the abolitionist movement gaining ground in the 18th century, seemed to probe the ethics of treating humans as objects or animals.

A Hackney-Coach, one of the subjects of the ‘it-narrative’. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

But what made it-narratives possible and appealing to readers was that this was a time when an object could plausibly travel farther than a single human would. By the publication of Chrysal in 1760, Britain was a growing colonial power, with possessions in North America, the East and West Indies, and India, as well as established trade routes to Africa and China. Objects, sometimes coming from places inconceivably distant, were increasing in abundance and the Western public’s relationship to those objects was in flux. “What connects the world is not shared religion or nationality, it is trade, it’s an object passing from hand to hand,” explained Blackwell. “I think increasing access to goods and changing relationships with things is part of what’s going on in these texts.”

It-narratives also reveal an anxiety about objects, in ways that hadn’t been expressed before. The it-narrative uses an object or animal’s ability to travel to convey a kind of personhood on to it; it’s perhaps no coincidence that these kinds of stories emerged at a time when philosophy, in the work of thinkers such as John Locke, was becoming very interested in the question of personal identity and what makes a self. How are objects, then, different from people? Even closer, how are animals different? “There’s a lot of angst about how these categories work in the 18th century and I think of it-narratives as a demotic, popular expression of that,” says Blackwell.

Perhaps not surprisingly, with their emphasis on anthromorphoized main characters, more adult it-narratives gave way to children’s versions. Within 20 years of Chrysal’s publishing, books aimed towards children with titles like The Adventures of a Whipping Top and The Adventures of a Pincushion routinely appeared at booksellers. These books were intended to have instructional value for children, reinforcing “good” behavior and existing social structures.

East India House in London, painted by Thomas Malton the Younger, c. 1800. (Photo: Yale Center for British Art/Public Domain)

In other words, these were not exactly nuanced social portraits. “They’re hard to read because they’re so overtly moralizing, because the good kids are the ones who take care of their stuff and the bad kids don’t,” says Blackwell, noting that we draw these same kinds of moral conclusions in children’s media today—think evil Sid, the toy-torturer in Toy Story, versus good guy Andy. Blackwell pointed to an essay in the book he edited that reads it-narratives as the product of two forces—an Enlightenment-driven de-sacrilization of daily life and the increasing importance of trade and commercialization. The result, says Blackwell, is that “the notion that there is a kind of omniscient or omnipresent god watching everything you do is replaced with the notion that the world is animated in some way and so you’d better be careful.” It’s a rather paranoid vision: you’re never safe from scrutiny because the walls can talk and they’re talking about you.

Children’s fiction became the refuge of it-narratives and still is: From Black Beauty, Beautiful Joe, The Velveteen Rabbit, and The Little Engine That Could, on through The Giving Tree, The Miraculous Story of Edward Tulane, the Toy Story trilogy, and the forthcoming Secret Life of Pets. It-narratives, for most of the adult literary establishment, were too clunky, too obvious, not real enough; one critic, writing in 1929, branded them “a misuse and often prostitution of the craft of the novelist”. And yet, there is a clear line from it-narratives to how we tell stories outside of children’s fiction now. The descendents of it-narratives are more subtle than Chrysal and his ilk, but they are found in modern literary fiction such as Nicole Krauss’s 2010 Great House, about a desk and the lives that are affected by it; in films, such as 1998’s The Red Violin about the ill-fated owners of a red violin stained with the blood of a woman who died in childbirth, or 1942’s Tale of Manhattan, about the owners of a black formal jacket; or The Hare with the Amber Eyes, a memoir about the fortunes of family collection of Japanese netsuke, a beautiful meditation on the arbitrariness of survival.

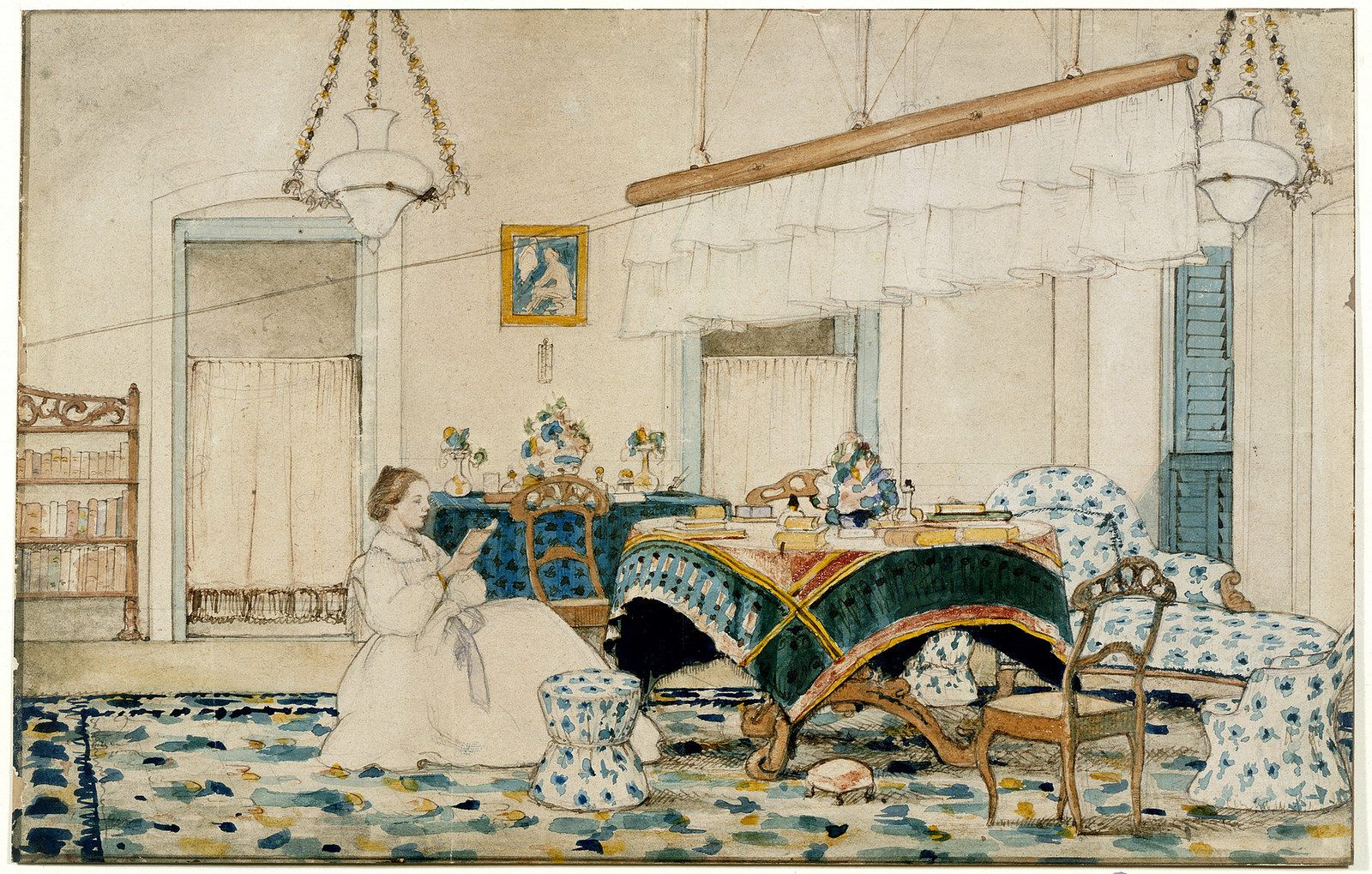

A woman absorbed in her reading, in Berhampore, India, 1863. (Photo: British Library/Public Domain)

Perhaps the strongest link between the 18th century style it-narratives and modern it-narratives is in journalism and the rash of books with titles like The Secret Life of Lobsters, Salt: A World History, and The Paper Trail: The Unexpected History of a Revolutionary Invention, or revealing articles like the New York Times’ 2002 “How Susie Bayer’s T-shirt Ended Up on Yusef Mama’s Back”. (The podcast Planet Money elaborated a bit more on the t-shirt, doing a whole series charting its construction overseas.) Modern it-narratives don’t so much imbue an object with personhood as they explore what it means to be an object in a world of humans, how objects come to have meaning, and how that meaning helps us make sense of our own history.

A bookstore in the late 1800s. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-det-4a20723)

The anxiety about technology and objects has remained constant since the dawn of it-narratives. Like 18th century readers, we are interested in the transit of objects and knowledge around this shrinking world and, like them, we’re finding ourselves with an increasing amount of stuff—although on orders of magnitude much greater with the average American home stuffed with more than 300,000 items, according to the Los Angeles Times, versus the dozen or so household possessions in many European households through the 19th century. And like them, we’re interested in the emotional lives of the things that we create and live with, if films like Her, AI, and Ex Machina are any barometer.

The concept retains currency because we remain interested and invested in the stories things tell; we’re curious about what they touch and, perhaps more importantly, how they define us or explain us. As Blackwell notes, “You can see the world in a particular way from the perspective of a thing,”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook