How to Dig Into the History of Your City, Town, or Neighborhood

Even a short local walk can hold countless stories.

During the past few months of lockdown, I’ve been taking daily walks around my Brooklyn neighborhood. As I’ve strolled the same streets week after week, I’ve started paying attention to buildings in a way I never had before. My roommate and I turned this into a sort of historical scavenger hunt. Each of us takes photos or writes down addresses during our separate constitutionals, and back at home we look up the history of the buildings. We’ve learned that a luxury condo building was previously a 19th-century home for “respectable aged and indigent females,” that a stately brick house was the mansion of a wealthy piano manufacturer, and that, between the 1880s and World War II, our neighborhood was a thriving shoe manufacturing district.

Wherever you live, the built environment tells stories. During this period of limited movement, uncovering those stories can help you feel a sense of discovery, even in your immediate surroundings, even among the very familiar. “Every community has value, and one of the ways you can realize it is to start looking, and analyzing, and thinking about it,” says Gabrielle Esperdy, a professor of architecture and design at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, and the editor of SAH Archipedia, a digital encyclopedia of more than 20,000 American buildings.

You don’t have to live in a city or a historic district to uncover something fascinating. Spaces that might seem mundane—even gas stations, water treatment plants, or empty lots—all “tell us something important about the choices we’ve made as a society,” Esperdy says.

Here are some expert tips for researching the history of your block, neighborhood, town, or city.

Sharpen your observation skills

To start paying closer attention to familiar scenery, you might have to “train” your senses. Historian, artist, and Black Gotham Experience founder Kamau Ware suggests a “discovery walk,” in which you focus on noticing your surroundings. “It could be something simple,” he says. “Listen to conversations in passing. Notice new cloud patterns. Try to figure out what someone is cooking.”

You might want to bring a pencil and some paper. Kurt Kohlstedt, digital director at the podcast 99% Invisible and coauthor of the forthcoming The 99% Invisible City, recommends drawing as a way to train yourself to really see what’s in front of you. “Once you start paying attention to shapes and contrast, you begin to train your brain to see things as they are, not how you imagine them to be,” he says. Taking photos or videos works, too. “Anything that forces you to think about framing and details can help you see in new ways,” Kohlstedt says. “Those details come with stories—histories of nature, infrastructure, and people that can be truly fascinating.”

Question every detail

“Start by asking the most obvious things,” says Ware, like finding the origins of your street and neighborhood names using a simple Google search. Kohlstedt suggests breaking down each thing you see into its constituent parts. “Instead of seeing just ‘pavement’ or ‘wall,’ force your eyes and mind to dig deeper, look for things you don’t even know the names for—what are the building blocks that make up that bigger, more obvious stuff?” For example, “where does the consistency of a surface break down, punctuated by an exception, like a manhole cover on a street or a Knox Box on a building?”

Find and read patterns

Once you’ve trained yourself to notice details, you can begin piecing them together into patterns. “No matter where you live,” Esperdy says, “if you simply start looking at patterns of what we see on any given block, we realize that there are encyclopedias worth of information.”

For instance, reading the “rhythm of the streetscape,” as the late architectural historian Virginia Savage McAlester wrote in A Field Guide to American Houses, can reveal insights about an area’s growth rate and economic origins. A neighborhood with many houses of the same age and type likely developed rapidly (like a streetcar or postwar suburb, or a railroad boomtown), while a town that developed more slowly will have a mix of house sizes and styles. A new apartment building much taller than the surrounding structures could signal changes in zoning or expired deed restrictions, while empty lots in a historic area might indicate a declining population.

On a smaller scale, even the presence (or lack) of the humble front porch can date a building or neighborhood. As Esperdy explains, from the 19th century to World War II, front porches were widespread in American homes. Before air conditioning, they offered a place to cool off, and socialize with neighbors (just like stoops in denser areas). In the postwar housing boom, front porches largely disappeared, thanks to indoor climate control, new ideas around socialization, the rise of the backyard, and the influence of Frank Lloyd Wright, who believed the front of the house should be private. (In the late 1980s, the front porch was reintroduced in traditional neighborhood developments, or planned communities inspired by historic neighborhoods.) The front porch alone, Esperdy says, “tells us about changing technology, about community interaction, and also shifting notions of recreation.”

Dive into maps, building surveys, and even postcards

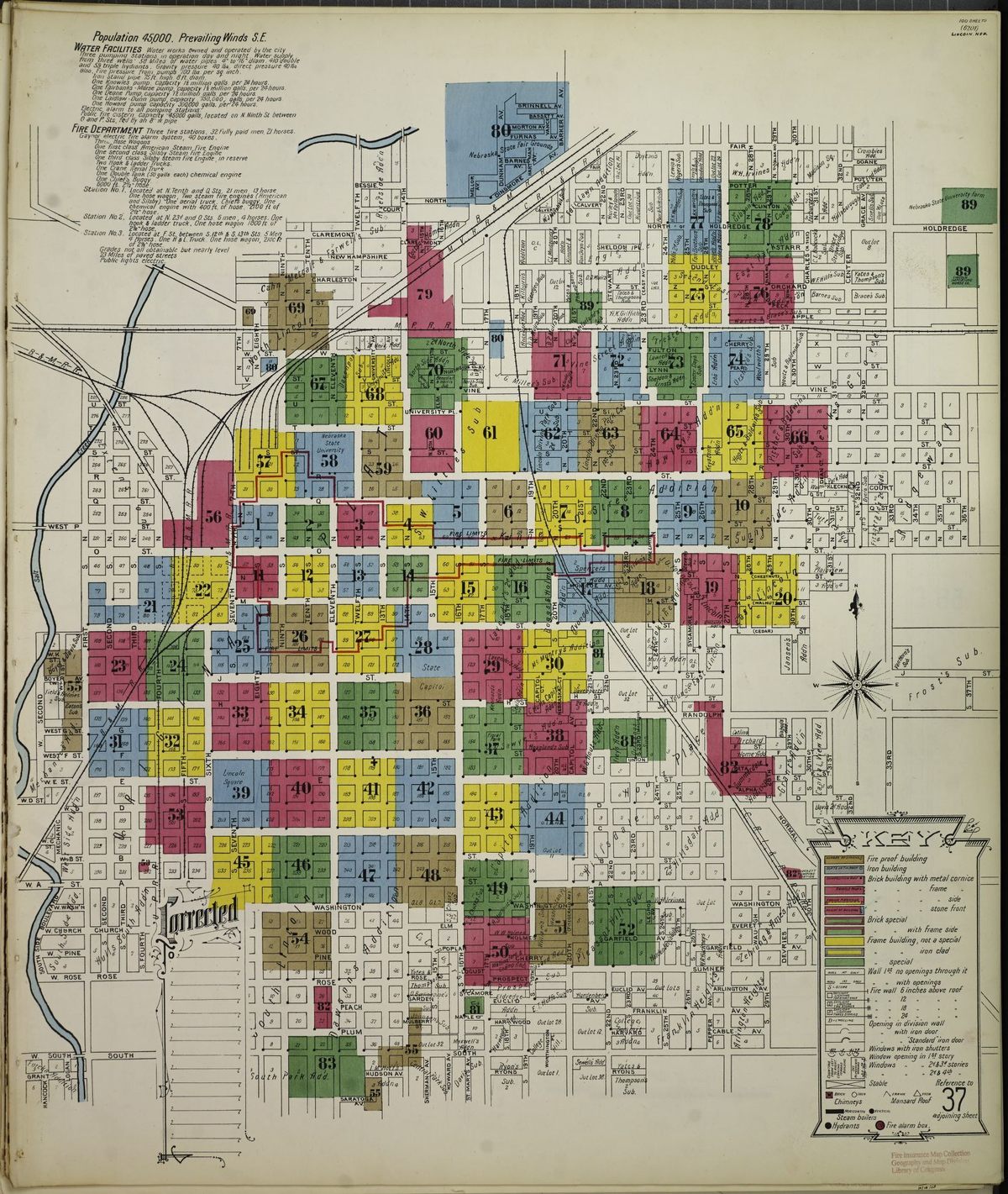

Once you’ve trained yourself to recognize the smaller details and larger patterns in the built world around you, next comes sorting out what those mean for its history. The digital resources of your public library or local historical society are a great place to start. Both Esperdy and Betsy J. Green, journalist and author of Discovering the History of Your House and Your Neighborhood, also recommend Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, available via the Library of Congress. “The maps give you an idea what the original footprint of a house was, and when it appeared on a particular piece of property,” Green says. Initially created to help agents assess fire risk during the post–Civil War urban development boom, the maps provide highly detailed information about land use and buildings—from door and window location to construction materials—for more than 12,000 towns and cities in the United States, Canada, and Mexico, from 1867 to 1970. Maps were periodically updated to reflect new construction (sometimes as often as every six months), and can show how a place changed over time.

Through the Library of Congress, you can also find photos and drawings from the Historic American Buildings Survey, the country’s first historic preservation program, created to employ architects, draftsmen, and photographers who were out of work after the Great Depression. Esperdy also recommends searching for your town’s name in eBay’s vintage postcard section. “Even if you live in Nowheresville, chances are there are postcards of it,” she says.

For city-dwellers, she also suggests Mapping Inequality, a site that combines 150 redlining maps from the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation—which outlined minority neighborhoods in red, to signal a “high risk” for mortgage lenders—into one interactive map showing how racism and discrimination shaped housing policy after the Great Depression. “It pulls us out from our individual block to the scale of the neighborhood and city as a whole,” she says, “and tells important stories about how we got to where we are.”

Find former residents

Learning about individual residents of your neighborhood—or even your home—can give more color to its history. Esperdy suggests searching an address in a periodical database such as Newspapers.com (your public library or historical society may also have a digitized database), which offers a week-long free trial, to find stories related to your house. If you own the house in which you live, Green says you should check your closing documents for an abstract of title, which lists all of the past property owners. She also suggests checking Ancestry.com (available for free for some public library card holders), for city directories, the late-19th- and early-20th-century version of phonebooks, but that also include details such as occupations and the names of adult children.

And, as Ware points out, “any citizen of the United States lives somewhere that was once the land of Native Americans or First Nations. See if you know the name of the people who were there.” (Native-Land maps are a great place to start.)

Indulge children’s curiosity

Get kids engaged in this research by encouraging them to do something that’s already second nature: Ask lots and lots of questions. “If you don’t know the answer,” Kohlstedt says, “don’t give a generic one. Be specific, or do the research and figure it out.” As Esperdy points out, Archipedia also offers lesson plans for grades K–12 on everything from basic architectural vocabulary to the history of the suburbs. (And for adults and older kids who want lots of detail, McAlester’s A Field Guide to North American Houses is a rich sourcebook.) Researching your neighborhood in this way, Kohlstedt points out, “keeps kids interested and entertained, but it also lets adults see through their eyes and notice the things that they’ve grown to take for granted.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook