I Made My Friends Test the 19th Century’s Hottest Dating Tactic: Reading Aloud

A slightly post-Victorian pair of readers in Bautzen, Germany. (Image: Abraham Pisarek/WikiCommons Public Domain)

There’s nothing like the onset of winter to remind you of how limited your idea of fun is.

Over the past couple of weeks, a cold snap has hit my hometown of Boston hard, significantly curtailing my social prospects. The idea of long walks or other outdoor pastimes is chilling, and my girlfriend and I have gradually exhausted all the offerings of every single local cinema. There are only so many Netflix deep cuts you can watch before the laptop screen starts feeling like a prison window.

As I sometimes do when dissatisfied with my own time period, I looked to the past for an answer. Stuck indoors one evening, I read about how young Victorian couples managed to skirt their own considerable restrictions and stoke passions by reading out loud to each other. I was intrigued.

Though I want nothing less than to be a Hipster Victorian, further research only made me more convinced that a period-appropriate read-aloud session might alleviate certain of my friends’ and my problems. As Godey’s Lady’s Book put it back in 1863, “reading aloud is one of those exercises which combine mental and muscular effort, and hence has a double advantage”—perfect for those boring, cold days when your mind and your muscles both feel frozen.

Girded only by my wits and some willing co-experimenters, I set out to learn more about what makes reading aloud so racy.

The Pastime

A Victorian-era painting, by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, of friends reading aloud to each other way back in Homeric Greece. (Image: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

As I quickly learned, for Victorian teens, reading aloud was a way to get wrapped up in the times and in each other. The industrial strides of the 19th century meant an explosion of printing technologies and a flurry of new reading material, explained my indulgent expert—Natalie Houston, Associate Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Lowell—in a phone interview. Literacy rates swelled, and the first newspapers and magazines appeared. Like today’s finest periodicals, many of these forerunners bore the happenings of the day along with more evergreen content: serialized fiction, histories, and travel writing.

Reading aloud made for a popular social activity, and was also a way for those who could read to fill in those who could not. Better-educated butlers brought their brethren up to speed on current events in the servants’ quarters, and dads read Dickens to their kids in the parlor. Even Charles Darwin took breaks from fielding responses to On The Origin of Species in order to read the latest Wilkie Collins mystery to his family, calling it “wonderfully interesting,” said Professor Susan David Bernstein of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who also indulged my inquiry, also over the phone.

Meanwhile, attractive young people, being quite Darwinian themselves, read to other attractive young people. “Maybe this is obvious,” Bernstein says, “but in the 19th century, there wasn’t radio, there wasn’t television, there wasn’t the internet.” For teens, there wasn’t even furtive snogging—as Houston adds, young people “weren’t allowed to be alone with [their] love interest in respectable, upper-middle-class society.” Instead, they had to make do with reading aloud, an activity suffused with intimacy-increasing contingencies. During dusky English (or New English) winters, reading required gathering close around an oil lamp or a bunch of candles. If two people were sharing a book, “you have to lean in close to look at the picture, and all that kind of thing,” Houston says.

You also got to look at each other, and to ham it all up a little, all without breaking the rules. “Reading aloud is a way for two people interested in each other to be sharing in an activity that is perfectly acceptable in the eyes of society,” says Houston. “But with the addition of significant glances as you’re reading a particular passage, or the emotion you put into your reading, it could charge a sort of ordinary situation.”

The Book

John Ruskin, painted in his preferred style by John Everett Millais in 1853 or 1854. (Image: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

So far this sounded good. Now I just had to choose a work. For help with this, I turned to Frederick Law Olmsted, 19th-century ladies’ man and designer of such romantic vistas as Central Park and the Niagara Reservation.

Before solidifying himself as an American genius, Olmsted was a dramatic twentysomething, prone to writing sentences like, “The sun shines, ice is cold, fire is hot, punch is both sweet and sour, Fred Olmsted is alone, is stupid, is crazy and is unalterably a weak sinner and unhappy and happy.”

Throughout his early decades, Olmsted and his brother John courted several young women by reading aloud to them from a book called Modern Painters. Though it may sound like the opposite, the work, by the British art critic John Ruskin, was a heart-pumping choice. Ruskin was himself young—24 when the first volume of Modern Painters came out—and had thrown himself into the task of completely overturning the current art establishment, championing painters who emphasized the truth and beauty of nature over the more rigorously composed landscapes favored by the post-Renaissance Old Masters. “This was really exciting stuff,” says Houston. “I can imagine that selected readings from Ruskin could have a lot of emotion attached to them.”

Olmsted was introduced to Modern Painters by a woman named Sophia Stevens. “The Modern Painters improves on acquaintance and Miss Stevens forms an amalgam with it in my heart,” he wrote. “She is just the thing to read it or have it read to one by.” When she later became engaged to another man, Olmsted bemoaned the loss of someone “to whom he’d been bold enough to read Ruskin,” according to biographer Justin Martin. (Meanwhile, brother John used the book to court another woman, Mary Perkins.)

Ruskin wrote prolifically, and his work was collected into thick volumes, allowing his fans and their paramours to enjoy Netflix-style binges of radical Pre-Raphaelite art opinions. His breathless prose and rhapsodic descriptions also influenced authors we’re more likely to think of as sexy, like George Eliot and Charlotte Brontë, who wrote that Modern Painters “seems to give me eyes.”

This was enough for me. Armed with the perfect tome, I convinced some friends, some coworkers, and myself to bring Modern Painters into a variety of romantic situations, from first dates to longtime evening rituals. Here’s what went down.

The Dates

A couple demonstrates their favorite activity for an 1895 photo. (Image: John Oxley Library/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.5)

Blake Olmstead,* 27, first date

With plans for wine and tapas before a show set, I knew this was my chance to become the Ruskin-reading romancer I knew I always was. In a chic midtown New York wine bar, I pulled out my Kindle and in the dim candlelight among the plate-filled table, I began to read aloud to my companion. He quickly started thumbing through the wine menu. For a second drink? You just said one was enough. Fidgeting? Can you really not sit still and listen for the length of this paragraph? “It’s a bit too loud here, maybe I’ll wait until we’re at the theatre,” I said. Sure.

We took our seats near the orchestra pit and in our new surroundings I began to read again. I chose a passage on the truth or power of history or age, thinking it would be fitting as we were now in a theatre over 100 years old. I could sense his interest waning and caught a few over-the-shoulder side-eyes and grew self-conscious. I stumbled over words and lost my place on the page. To hide my insecurities and fumbling, I turned the conversation to the building itself, but realized I had mistaken a “must not” in the text for a “must” and spouted on about how we must not fetishize the histories of a place when thinking of its future values when the text very nearly said the exact opposite. What would Jane Jacobs think?

Between two people the exercise revealed nothing except perhaps my companion’s inability to focus on anything that doesn’t originate within himself.

Next time, I’ll stick to reading to my fern.

*no known relation to Frederick Law.

Urvija Banerji, 22, in a relationship

Let it be known that my boyfriend was beginning to get sick, and by this point he was under the covers and entirely ready to fall asleep, so in some ways I was set up for failure. In preparation, I had already scoured Modern Painters for any sign of racy passages, and having found none, I settled on the chapter, “Of Ideas of Beauty,” in the hopes that it would make him gaze upon me with adoration and admiration.

I was not very good at reading things aloud at school, but my teachers would never fail to call on me to read out passages to the class. This childhood trauma has meant that reading things out loud in adulthood always gives me anxiety. So with some trepidation I began reading “Of Ideas of Beauty.” About halfway through the second paragraph I began to get the feeling that my boyfriend wasn’t following along. Heck, I wasn’t even sure I was following along. But still I prevailed, hoping that by reading about beauty he would be overcome with his own ideas of my beauty.

Alas, the chapter became increasingly religious as I went on, and any notions of romance immediately went out the door. I hopefully looked up at my boyfriend as I said the words, “individuals possessing the utmost degree of beauty which the species is capable,” pausing to give him time to respond. He responded by blinking sleepily.

Christina Couch, 34, married

I would label this experience as a fairly romantic thing. [My husband] Jason and I curled up in bed and read this weird thing aloud while the dog slept on her bed nearby and punctuated our laughter with farts.

John Ruskin is a dude with a very clear sense of things that are capital-O capital-K and things that are not, and therefore deserves to be read aloud in a Foghorn Leghorn voice. I liked how angry he got at various artists, and I can picture Victorian teens reading this out loud and being like “AW SHIT, JOHN RUSKIN THROWING SOME SHADE AGAIN!”

Overall, I have very little idea of what John Ruskin is talking about, but Jason and I did laugh out loud when he states in the preface that he allowed the publication of a new edition of his book “though with some violence to my own feelings” and with “a narrow enthusiasm.” I would say that I have a narrow enthusiasm for this book in general.

Reading aloud was a nice alternative to watching TV or a movie. We certainly talked and laughed a lot more doing this than we usually do watching TV on a week night.

Your correspondent, Cara Giaimo, 26, in a relationship

My girlfriend Lilia and I brought a library copy of Modern Painters to our local bathhouse, Inman Oasis in Cambridge. We figured that, although the privacy of the experience was less than historically accurate, the obscuring steam would provide plenty of opportunities for smoldering glances. For ambience, we queued up Romantic composer Richard Strauss, leading off with his version of Bach’s moodsetter “Air on a G String.” (We later found out that Strauss never performed “Air on a G String,” and that we were instead listening to the Johann Strauss Orchestra, which was founded in 1987. Inauspicious.) Jets firing around us, I set the huge hardcover on the edge of the tub, flipped to Volume I, Section V, “Of Truth of Water,” and began to elocute.

Although phrases like “the radiating and scintillating sunbeams are mixed with the dim hues of transparent depth” made me better appreciate my immediate surroundings (water can be so deep, man!), trying to get my vocal cords around them left me sputtering and gasping. The idea of practicing reading particular passages aloud—which I had previously dismissed as the kind of extra-performative hobby that rightly died with Godey’s—suddenly seemed like a vital courting skill. As I tried and failed to properly deliver Ruskin’s impassioned critiques, my normally patient girlfriend began doing tiny laps, then loudly splashing. If there had been tomatoes around, the tub would have quickly become soup.

Things went better when Lilia tried it. As someone who regularly takes apart arcane subjects in front of crowds, she triple-axeled the impenetrable sentences like some kind of syllabic ice dancer. Though I didn’t really understand what she was talking about, I was convinced by her conviction. I put on my best smoldering faces—but she, of course, was having too much fun reading to see them.

What We Learned

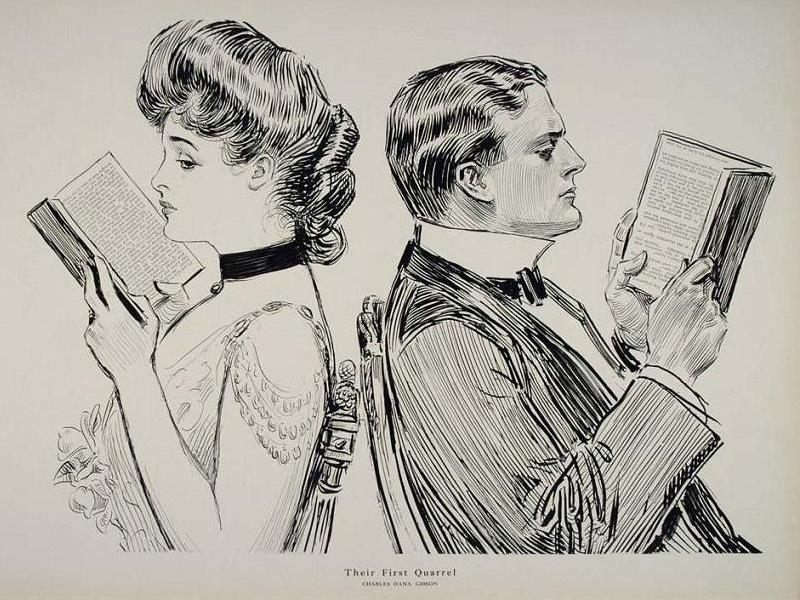

In “Their First Quarrel,” by Charles Dana Gibson, reading alone is a sign of rough times. (Image: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

Early in our conversation, Professor Houston told me that reading aloud was also popular in families because “other members of the household could be doing useful or recreational tasks” while one parent read. Women would work on their embroidery or sewing, and “boys and men might oil small machinery or do little bits of woodworking projects,” Houston said. “Little things you can do with your hands that don’t require a lot of light.”

In our tests, and with such dense material, the aspect of reading aloud that allows the listener’s hands and mind to wander seemed to overshadow any aspect that leads to a more Olmstedian heart-amalgam. Only readers that were able to let their own personalities show through—to be “true to nature,” as Ruskin might say—came out feeling like they’d added new colors to their love-landscape. Taking turns in the driver’s seat also led to increased success.

One thing is for sure—a tried-and-true way to beat the winter doldrums is to make your friends do something weird and then tell you about it. Check back next time when I try to convince a new batch of guinea pigs to marry a ghost.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook