In 1562 Map-Makers Thought America Was Full of Mermaids, Giants, and Dragons

Sea serpents, cannibals, and one of the earliest mentions of California are features of this spectacular map.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the mysterious lands of the western hemisphere were a misty haze of tales and stories. After Christopher Columbus set foot in the New World, curious Europeans ate up fantastic sagas about sea monsters, exotic wildlife, and foreign civilizations. Teasing out fact from folklore created an ever-growing obstacle for depicting what the Americas truly looked like.

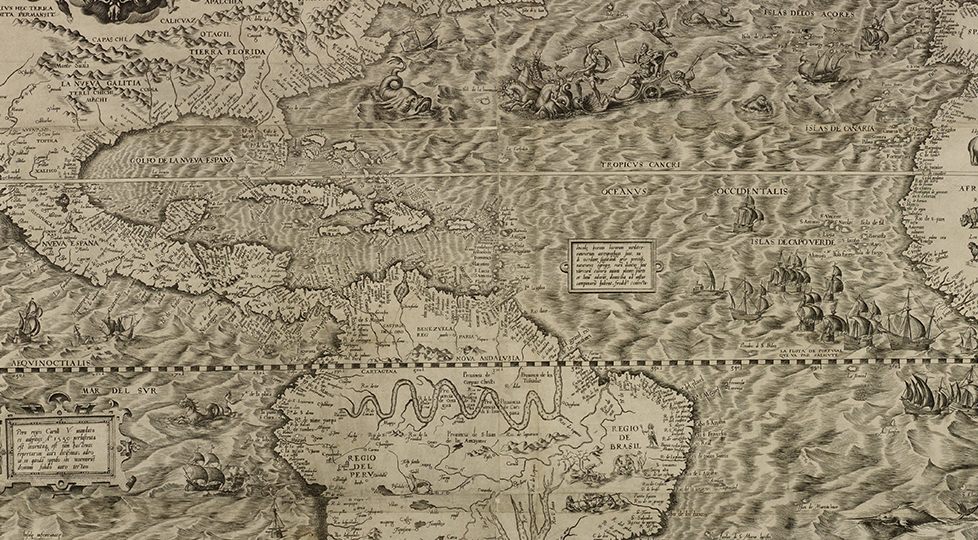

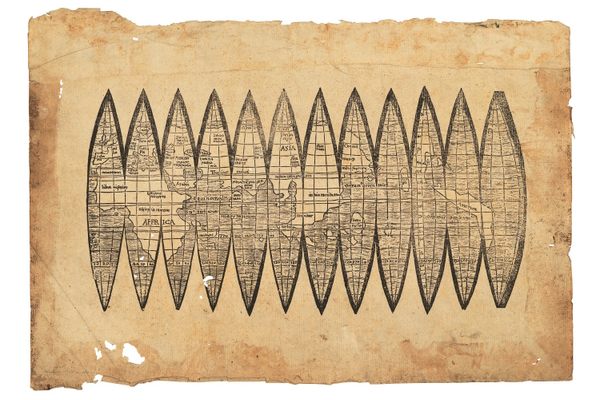

In 1562, Spanish chartmaker Diego Gutiérrez and Dutch engraver Hieronymous Cock made such an attempt. They visualized the New World in a massive six-paneled engraved map—the largest engraved map of America of its time. Published in Antwerp, Americae sive quarte orbis partis nova et exactissima, Latin for The Americas, or A New and Precise Description of the Fourth Part of the World, served as artwork, informational chart, and political document.

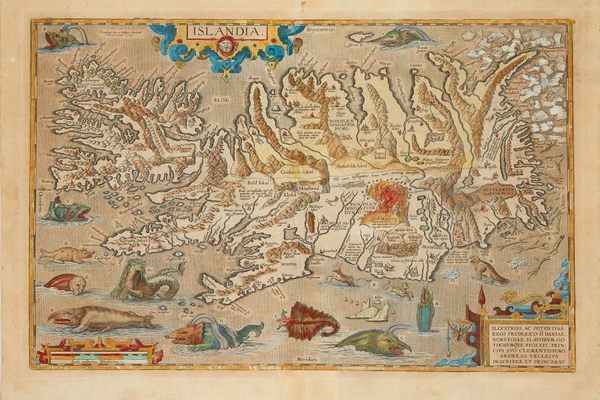

While the intricately engraved map depicts accurate geographical features in many cases (the east coast of the Americas, and the west coasts of Europe and Africa), it is also riddled with propaganda and folklore. Many of the legends and rumors about the New World circulating at that time can be found in the map, too: mermaids, hungry sea serpents, cannibals, a massive erupting volcano in Mexico, and a land of giants.

“I think the Europeans were much more interested in seeing another world [different from their own],” says Aquiles Alencar Brayner, the British Library’s curator of Latin American collections, in a video.

As a respected mapmaker for King Phillip II and Spain’s official trade agency, Casa de Contratación, Gutiérrez was exposed to adventurers’ stories and the riches imported from South America. In depicting the Americas, the Seville-based mapmaker dots the map with many of the popular names and labels that were circulated by European explorers.

Since most people in 16th-century Europe couldn’t read, maps were not only a navigational tool, but a popular medium to tell stories about specific places and civilizations, Alencar Brayner explains.

Gutiérrez drew an assortment of wildlife that had been observed by explorers, including monkeys, parrots, an elephant and a lion. But strangely, an Indian rhinoceros is found poised in the African plains.

Explorers had seen documented accounts of rhinos in Africa, however the illustration in the map is actually a copy of Albrecht Durer’s 1515 depiction of a rhinoceros native to India.

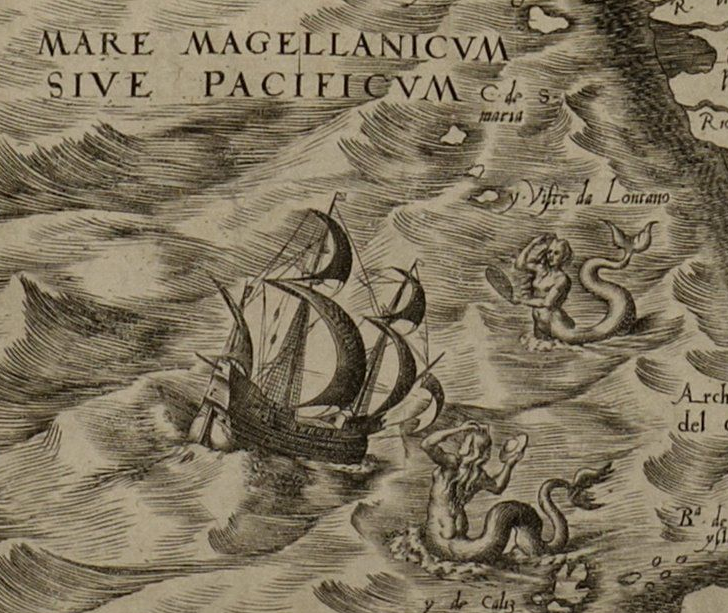

Like many other 15th and 16th-century maps, the treacherous oceans are terrorized by an assortment of terrifying sea monsters, reflecting the fear of the unknown and uncharted waters. In the Atlantic Ocean west of Ireland a massive clawed creature lurks in the waves.

A flying fish can be spotted just below a ship battle in the lower right panel, while a strange-looking ape or monkey seems to be gnawing on its prey just west of the Canary Islands.

The west coast of South America appears particularly dangerous and mysterious. There is a menacing whale ramming into a ship, a dragon serpent, and a group of mermaids holding what looks like a UFO-shaped disk near today’s Patagonia—a legendary land rumored to be the home of giants.

Latin America was home at that time to highly resourceful indigenous peoples, says Alencar Brayner. The Aztecs and the Mayans knew how to work with metals, cultivate land and farm, and preserve artifacts. But the map doesn’t depict these people. Instead, Brazilians are drawn as barbaric cannibals in the midst of butchering and roasting humans.

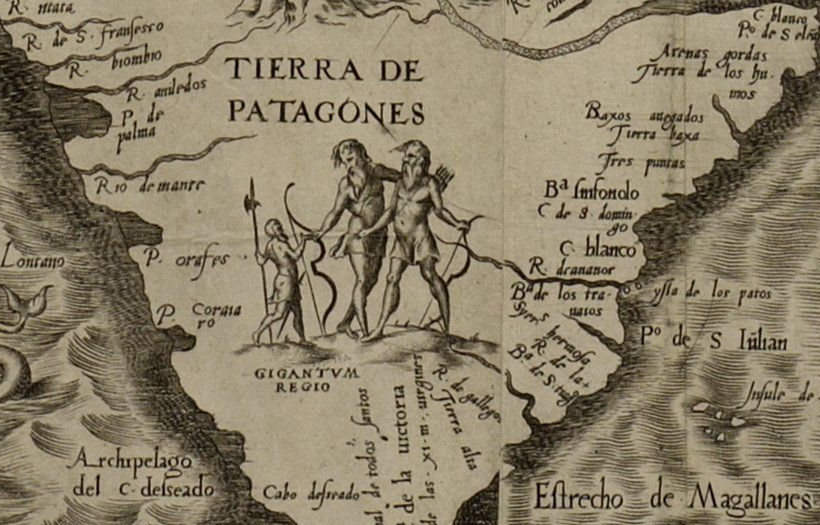

In southern South America, Gutiérrez shows two members of the Tehuelche tribe as large giants looking down at an explorer in “Tierra de Patagones,” or the land of giants.

The region, which now constitutes parts of modern Argentina and Chile, was described by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan after encountering the native Tehuelche tribe in 1520. According to his accounts, the Tehuelches were said to have been anywhere from six to six-and-a-half feet tall, and “appeared gigantic to the relatively short-statured Spaniards,” wrote Irene Butler in Langley Advance. Magellan said that his men only reached up to the giants’ waists.

To prove that he had found giants in the New World, Magellan captured two of the Tehuelches and tried to bring them back to Spain. However, they didn’t survive the trip, and Magellan was only left with his and his shipmates’ tales of the land of giants. It was given the name Patagonia, which derives from “pata,” the Spanish word for foot.

Magellan’s bizarre encounter with giants was later disproven by Sir Francis Drake when he explored Patagonia. He wrote in 1628: “They are nothing so monstrous and giant-like as they were represented, there being some English men as tall as the highest we could see.”

While there is obvious fictitious material in the map, Gutiérrez and Cock also name settlements, rivers, mountains, and capes that exist today. They show rough etchings of the Amazon River, Lake Titicaca, Mexico City, and rivers in South America and Florida. There are many correct coastal features of South, Central, North, and Caribbean America, writes John Hébert in the journal The Hispanic Outlook in Higher Education.

The map also contains one of the earliest references to the name California—“C. California” denoted in tiny print on the very left side at the southern tip of today’s Baja California.

While the map achieves the general outlines of what we know America to look like, the map was not intended to be scientifically or navigationally exact, explains Hébert.

“It was, rather, a ceremonial map, a diplomatic map, as identified by the [Spanish] coats of arms proclaiming possession,” he writes. “Through the map, Spain proclaimed to the nations of Western Europe its American territory, clearly outlining its sphere of control.”

Spain’s power and dominance as a world power is hinted at often in the map. In the upper left corner are the Spanish arms of King Phillip II, who makes an appearance on the map. He is depicted like a majestic god cutting through the waves of the Atlantic Ocean in a chariot behind the Greek god Poseidon.

The panel of script in the lower left tells of the conquests of Alexander the Great, subtly aligning the Spanish Empire with the accomplishments of powerful rulers and conquests of the past.

“It’s interesting to see the relationship between map drawing and power,” says Alencar Brayner. “By the time you can map something, you can point out that it’s belonging to you.”

Even though Gutiérrez and Cock’s map of the Americas is full of visual splendor, a lot can be read between the lines. There were still more exciting wonders waiting to be discovered in the New World.

Map Monday highlights interesting and unusual cartographic pursuits from around the world and through time. Read more Map Monday posts.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook