In 1926, Houdini Spent 4 Days Shaming Congress for Being in Thrall to Fortune-Tellers

The congressional hearings on the supernatural were very theatrical.

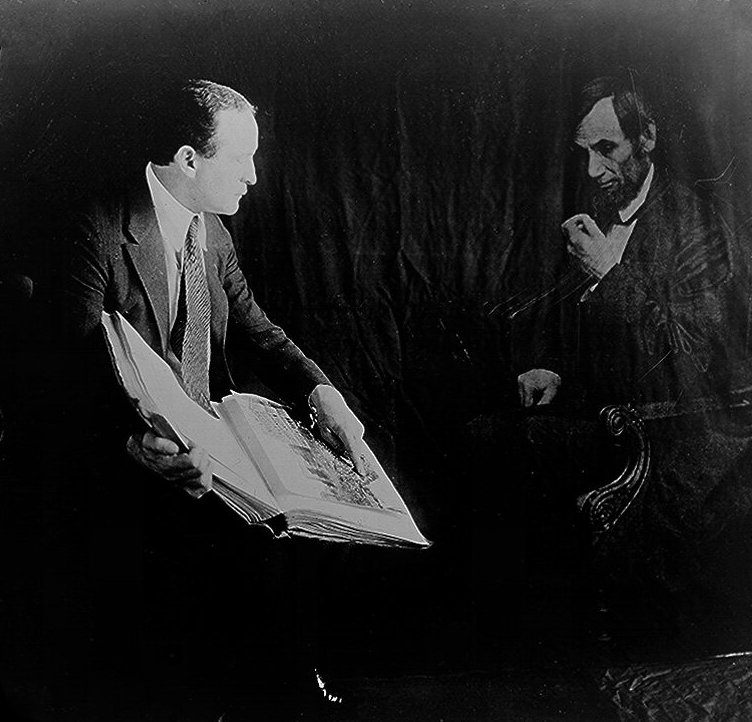

Harry Houdini with Senator Capper on 26 February 1926, during hearings on the fortune telling bill, with mediums seated in the background. Capper was among the senators implicated as a client of astrologer Madame Maria. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-npcc-27498)

Harry Houdini, testifying before a subcommittee of the United States Congress in 1926, brandished a sealed telegram and demanded that someone in the audience tell him the contents of the message inside. The chamber was packed with spiritualist mediums, psychics, and astrologers who had turned out to fight against Houdini’s bill, House Resolution 8989, which would ban the practice of “fortune telling” in the District of Columbia.

If the mediums couldn’t read the telegram, Houdini argued, they belonged in jail for hawking fraudulent psychic powers.

None of them took the bait, but Representative Frank Reid of Illinois piped in with a phrase that turned out to be correct. “That’s a guess,” Houdini scolded, “you are no clairvoyant.” “Oh yes, I am,” was Reid’s unexpected rejoinder, met with chuckles from the audience.

This was no laughing matter for Houdini. The famous illusionist claimed that America’s elected officials were in thrall to psychic mediums, and that this posed a danger to the nation. At the time, most people saw nothing harmful about seeking clairvoyant advice; it seemed amusing and potentially useful. Indeed, spiritualism and the occult enjoyed renewed popularity after World War I.

The congressional hearings on the matter careened on for four raucous days. Order in the chamber disintegrated, police were repeatedly summoned, and the husband of a medium nearly punched Houdini in the face. Meanwhile, newspapers nationwide had a field day with headlines like “Hints of Seances at White House” and “Lawmakers Consult Mediums”.

Yet it was Houdini’s crusade that helped swing popular opinion on spiritualism, turning belief in psychic powers into a sign of gullibility or even madness that would spell doom for any political campaign.

Houdini leaving the first day of Congressional hearings on H.R. 8989. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-npcc-27425)

In advance of the first hearing on February 26, Houdini sent his undercover investigator, Rose Mackenberg, to comb Washington’s underbelly for mediums. Armed with this evidence, the celebrity magician rolled into town to deliver a case against the supernatural that he’d made many times, part skeptical exposé, part witty entertainment. Word of the bill had spread through the spiritualist community by way of sympathetic lawmakers, and local mediums turned out in force, led by spiritualist minister Jane B. Coates and astrologer Marcia Champney.

H.R. 8989 would impose a $250 fine or six months in prison for “any person pretending to tell fortunes for reward or compensation” within the nation’s capitol. Of course, the bill was premised on the assertion that it’s scientifically impossible to see the future, therefore all mediums are “frauds from start to finish,” in Houdini’s words; either “mental degenerates…[or] deliberate cheats.”

Spiritualists, however, defended psychic communion with the dead as a matter of faith: “prophecy, spiritual guidance, and advice are the very foundation of our religion,” proclaimed Coates, pleading for protection under the First Amendment.

The congressmen, though often bemused, were relatively unbiased; they alternated between defending the supernatural and spoofing it, ribbing Houdini and mocking the mediums. They found many spiritualist practices laughable, but few agreed with Houdini that banning psychics was a matter of life and death—that spiritualism drove followers to the insane asylum with its “contagious moral degeneracy.” Rather, they fit spiritualism into a characteristically American religious patchwork.

“I believe in Santa Claus and I believe in fairies, in a way,” Representative Ralph Gilbert of Kentucky declared, “and [Houdini] is taking the matter entirely too seriously.”

Houdini demonstrating how is it possible to fake a “spirit photograph”, by documenting himself with Abraham Lincoln. (Photo: Library of Congress)

It soon became apparent, however, that many political families also took psychic predictions quite seriously. The wife of Senator Duncan Fletcher testified that she hosted mediums “in my own home circles of some of the most prominent people in Washington.”

To prove that Capitol Hill was corrupted by psychic influence, Houdini quoted statements that his opponent, Madame Marcia, made to an incognito Rose Mackenberg the previous day: “[Marcia] said a number of Senators were coming to her readings; in fact, most of the Senators…almost all the people in the White House believed in spiritualism.” If politicians, supposedly the nation’s best and brightest minds, were vulnerable to such delusions, then psychics were not just “innocent fun” – they posed a serious threat to democracy.

Coates, the spiritualist minister, had also boasted to Mackenberg of her power and influence in Washington. “Why try to fight spiritualism, when most of the Senators are interested in the subject?” she reportedly said. “I know for a fact that there have been spiritual seances held at the White House with President Coolidge and his family.”

The room erupted into chaos as Mackenberg proceeded to name names: Senators Capper, Watson, Dill, Fletcher. Houdini theatrically underscored her claim – the corruption went all the way to the top.

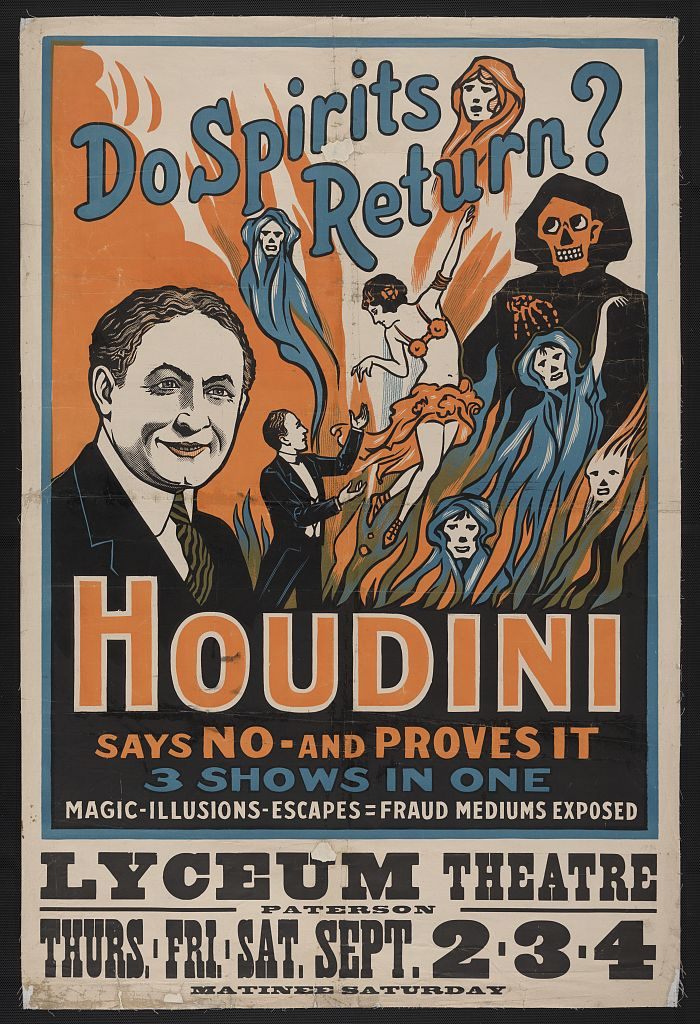

From Houdini’s stage show, c. 1909: “Do spirits return? Houdini says no - and proves it”. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-var-1627)

With this proclamation, Houdini perhaps unwittingly embroiled himself in a larger political drama. It was public knowledge that Florence Harding, wife of Coolidge’s predecessor Warren G. Harding, regularly consulted a psychic who predicted her husband’s election victory as well as his unexpected death in office. The former First Lady’s psychic advisor was none other than Madame Marcia. Marcia Champney eventually wrote her own exposé, When An Astrologer Ruled the White House, claiming that her foreknowledge played a pivotal role in the Harding administration.

After Coolidge stepped up to the presidency in 1923, he worked hard to put Harding’s many scandals and intrigues behind him. So when Madame Marcia and Jane Coates appeared in Congress trumpeting their psychic services to the White House, they brought with them Harding’s unsavory ghost. The same day as Houdini’s accusation, the evening edition of the New York Times carried an official denial “that seances had been held at the White House since Mr. Coolidge became president.”

Even Houdini realized that he had gone too far by dragging Coolidge into the dirt. On his way out of town he would hand-deliver his best attempt at an apology letter. “It was no desire of mine to embarrass the President,” he wrote, “but I am accustomed to accept the facts without garnishment, no matter how unpleasant they may be.”

While trying to smooth things over, Houdini couldn’t drop his righteous posture of exposing credulity among the powerful. He still suspected the 30th President of being a believer. Regardless of Coolidge’s private inclinations, his actions show how public stigma around the occult was becoming very real.

Madame Marcia, psychic adviser to President Harding’s wife Florence. (Photo: Library of Congres/LC-DIG-npcc-03755)

Meanwhile, debate over H.R. 8989 had jumped the rails, marred by ad hominem attacks and constant outbursts. The mediums lashed out at Houdini, calling him a liar and traducer, while the magician unrolled reams of tangential evidence, including an actual 50-foot long scroll. During breaks intended to restore order, the antagonists scuffled in the hallways. The theatrics reached a crescendo when Houdini issued his notorious ultimatum, defying all of the mediums present to produce a single verifiable psychic phenomenon.

He waved around an envelope stuffed with $10,000 in cash, declaring, “This is my answer to anything they say. If they can, here is the money.” Usually, this challenge produced a telling silence among his audience. However, the mediums of Washington were not so easily cowed.

“That money belongs to me,” Madame Marcia declared, saying she foresaw both Warren G. Harding’s election and his death. Though it’s not clear how Houdini could ever verify a prediction made six years earlier, at that point the testimony had become pure rhetoric on both sides, and the spiritualists broke into wild applause.

Madame Marcia was not awarded the cash. However, in the heat of the moment she made another prophecy, that the great illusionist would be dead by November. Houdini perished under mysterious circumstances on October 31, 1926.

Houdini exposes the techniques used by fraudulent mediums on stage at the New York Hippodrome, 1925. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-66388)

Despite Houdini’s best efforts to brand psychics as frauds and spiritualism as “a contagious mental degeneracy,” Congress declined to outlaw what followers claimed was a religious practice. It looked like a major defeat for the strident magician, but Houdini’s strategy never really hinged on legal enforcement.

Using his talent for showmanship and persuasion, he aimed to turn popular opinion against spiritualism. This change was far from instantaneous, but Houdini’s fame, combined with the scientific authority of psychologists like Joseph Jastrow, G. Stanley Hall, and Hugo Munsterberg, ultimately triumphed.

Taking his case to Washington was especially masterful: Houdini started at the top by outing elected officials, with lasting repercussions for the role of faith in American politics. Some beliefs—the mainstream kind—are still mandatory to prove a candidate’s moral character. But believing in less conventional forms of supernatural agency, like clairvoyance or astrology, is a serious liability.

In 1988, when President Reagan’s former Chief of Staff publicly outed his boss for using the predictions of an astrologer, an international controversy erupted; it was seen as an embarrassment and a security risk. But the fears and criticisms leveled against the Reagans were right out of Houdini’s anti-spiritualist playbook.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook