In a Ghost Town, Stuffed Animals Gather

In Dogtown (Photo: Sarah Laskow)

In Dogtown (Photo: Sarah Laskow)

Some places just can’t shake their pasts. Think of the atmosphere in an abandoned factory or the uneasy energy of a neighborhood “transitioning” from one demographic to another, to say nothing about the fate of a house built on top of an Indian burial ground.

Dogtown Common, an overgrown settlement a few miles north of Gloucester, on Massachusetts’ North Shore, is one of those spots.

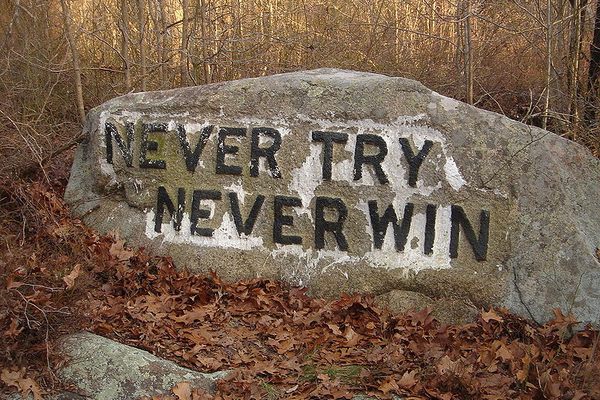

Once, the inland town was a desirable neighborhood. Starting in the 1720s, some of the Gloucester’s most well-off families moved to this high ground, where giant boulders had been deposited by receding glaciers. Cleared of forest, it promised safety from pirates (at least, that’s what locals say, although there’s little evidence that the few pirates working the area were a problem) or maybe from the British, as well as plentiful sources of drinking water, and room to expand from the growing port city.

They named this new town the Commons Settlement. By 1741, at the height of its popularity, about a fifth of Gloucester’s population had moved there. Soon, though, the city decided to move the meetinghouse, the center of the Puritanical lives of 18th century Massachusetts residents, further from the town, and living in the heights went out of fashion. By the end of the century, most of the people who lived in the area had little choice: they were poor widows, of sailors and Revolutionary War soldiers, and others not welcome in polite society.

The widows kept dogs to protect them, and those dogs, eventually run wild, may have given the area its new name, sometime after the Revolutionary War. But, as Elyssa East explains in Dogtown: Death and Enchantment in a New England Ghost Town, it wasn’t just that. “What changed the Commons Settlement to Dogtown was the people: women who dressed like men, men who did housework, alleged witches and former slaves,” she writes. Many of the women who lingered up in the town developed reputations as witches: the most notorious was Thomazine Younger, who went by Tammy. She was reputed to be short and plump, and her worst crime was scamming people out of money by threatening to curse them. (Which, if you’re already being branded a witch, seems like a pretty good business plan.) Another Dogtown woman, Granny Rich, had her own witchy line of business: She’d tell fortunes in coffee grounds.

By the 1830s, even these outcasts had left Dogtown, and the forest began to regrow. Even after last house was pulled down in 1845, the town never disappeared entirely: there are still walls and old wells and cellars overgrown and scattered among the trees. But Dogtown became an dark, foreboding place. Even a century ago, ”once there, you might walk in circles for a week without finding the way out,” a New York Times writer warned.

Today, there’s a map of the Dogtown Commons trails. But it’s not a good one, and even Google doesn’t have a strong sense of what goes once you’re just a little bit into the woods. Getting lost while walking the trails is inevitable, even for people who’ve been there before. And that is how my uncle and a friend of his found something very odd in the woods.

On Friday afternoon, they had set off on a walk, aiming to find the Whale’s Jaw, the most famous of the area’s boulders, and they had walked the wrong way—at least, they had never arrived at their destination. Instead, while trying to find their way through the forest, they came across something extremely strange, something straight out of a True Detective episode or a horror film about an abandoned children’s asylum. My husband and I decided we needed to see this for ourselves.

Finding Pooh Bear

There was no guarantee that we could find the site again. The best directions my uncle could give us would take us to the beginning of the trail, to an area in the north of Dogtown. After that, we’d be on our own. On the map, the area was crossed by more than a dozen of short, interconnecting trails, any of which could be the right one.

We parked our car a little outside the woods, and started towards the trailhead, walking down a gravel road, past big stone houses set in meadow-like yards, until we found the green metal gate. That marked the beginning of the trail. We’d already passed one wooden sign that warned “I’d turn back if I were u!” and though it was probably meant for some Halloween hayride—it featured an unhappy jack-o-lantern and a ghost that said “Boo!”—it wasn’t entirely reassuring, given the mission we were on.

A road not taken (Photo: Sarah Laskow)

A road not taken (Photo: Sarah Laskow)

We walked passed the green metal gate, and soon the path started following an old stone wall. Occasionally, it would break or turn down a side path: these, it seemed, were the old roads of Dogtown. Inside, the woods were green, cool, and quiet. We guessed at the route, passing one faint turn-off that disappeared between two grey boulder walls, chose a right fork at fallen tree stripped of its bark, and walked over a plank bridge before we came to a T in the path. Right or left?

We chose right, and not long after, in the middle of the path, we saw what my uncle had seen: the beginnings of a stuffed animal installation in the middle of the woods. A Pooh Bear perched in the fork of a tree. He’d been there for long enough that a spider had woven a thick web across his belly. To our left, we saw the rest of the stuffed animal coven, arranged in an occult gathering of toys that defied easy explanation.

Pooh blocks the path (Photo: Sarah Laskow)

Pooh blocks the path (Photo: Sarah Laskow)

To the left (Photo: Sarah Laskow)

To the left (Photo: Sarah Laskow)

Here’s what we saw:

(Video: Ben Furnas)

The Beanie Babies were arranged in a semi-circle on the side furthest from the path (Photo: Sarah Laskow)

The Beanie Babies were arranged in a semi-circle on the side furthest from the path (Photo: Sarah Laskow)

(Photo: Sarah Laskow)

(Photo: Sarah Laskow) The netted and blindfolded baby dolls were at the very center (Photo: Sarah Laskow)

The netted and blindfolded baby dolls were at the very center (Photo: Sarah Laskow)

What else is in Dogtown’s woods?

In the years after Dogtown was abandoned, its reputation as a mysterious and occasionally dangerous place grew. When East was researching her book, she was warned to avoid entry. ”People who went to Dogtown, got lost, and were never found again,” she writes. “I had heard similar stories myself. That they could not be verified did little to keep people from thinking that they might, in fact, be true.” There have been rumors of ghost dogs and, worse, werewolves in the woods, too.

But less phantasmic dangers have also found a place here. One local man allegedly killed a friend and buried him in the woods. In the early 1980s, a homeless man was found beaten to death, and then in 1984, a schoolteacher died here, after a local man attacked her with a rock. Locals have come to the woods to commit suicide, too. There’s enough sad and scary history here that it’s easy to conjure a very creepy mood with just a little imagination.

No one seems to know how long the toy coven has been there. Certainly sometime this summer, and probably within the last month or so. While we were in the woods, for maybe an hour and a half, we saw only a few other people—a lone hiker who was recovering from hip surgery, a couple with their dog, and a triad of teens on mountain bikes. “A few teenagers have committed suicide in this area,” the hiker said. “I’m not saying this spot is where that was, but it could be connected to that.” The bikers thought it was creepy, but had no information. The couple didn’t know who was responsible for the installation but, they said, their dog was scared of it.

Whatever those stuffed animals are doing in the forest, they’re now one more piece of evidence that Dogtown has become the sort of place where people seek out strange things—or make them happen. Anyone who wants to see this one, before it disappears, can enter Dogtown on the Dennison Trail, and aim for 42°39’20.7”N 70°39’07.3”W—those are the coordinates of the pin I dropped on Google Maps standing on the trail just in front of Pooh.

But even if you feel an eerie mood descend, just remember, it’s nothing new for Dogtown. Even without tied-up dolls and stuffed animals, back in 1873, the boulders alone were enough to inspire one Massachusetts man to write: “I know of nothing more wild than that gray waste of boulders…in that multitude of couchant monsters there seems a sense of suspended life; you feel as if they must speak and answer to each other in the silent nights.” This is just the type of place where people hear voices.

(Photo: Sarah Laskow)

(Photo: Sarah Laskow)

(Video: Ben Furnas)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook