James Bond’s Jetpack Escape in ‘Thunderball’ Almost Didn’t Happen

At least not as initially planned.

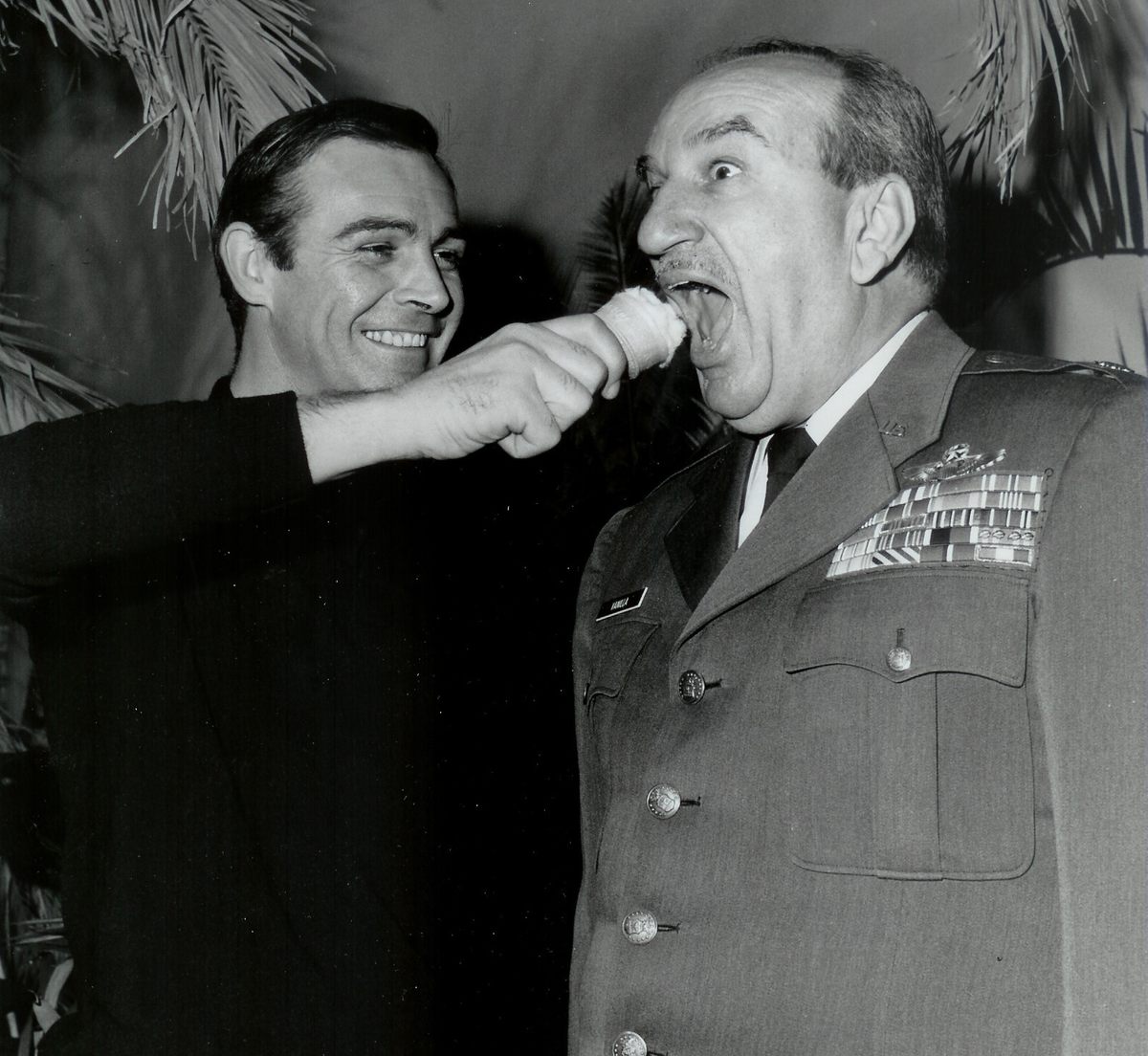

It’s May 1964, and a nervous energy permeates the air on the set of Thunderball, the fourth James Bond film starring Sean Connery. Soon enough, this jittery anticipation won’t be the only thing in the air.

Standing on the roofline of a French chateau, stuntman Bill Suitor is about to use a state-of-the-art jetpack to propel himself 20 feet into the sky.

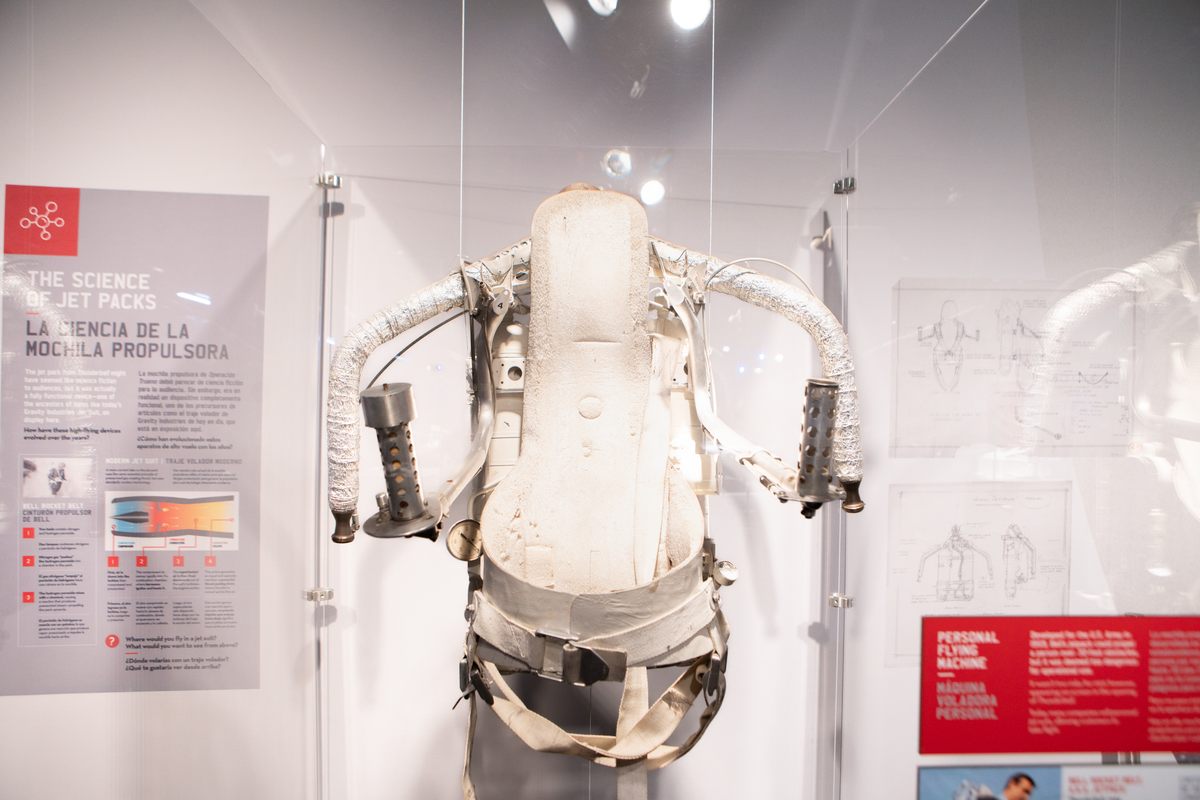

Today, this same jetpack, the Bell Rocket Belt, is on display at the Museum of Science and Industry’s exhibition, 007 Science: Inventing the World of James Bond. The exhibition, which runs through October 27, 2024, celebrates Bond’s ultramodern gizmos from the legendary film franchise.

Technology tends to figure prominently in Bond’s fast-paced world of espionage. Just as the franchise is known for introducing Oscar-winning theme songs and glamorous new “Bond girls,” the films also have a reputation for predicting future tech.

The developers of the Bell Rocket Belt, Bell Aerosystems, had originally designed the jetpack in the 1960s as a tactical rescue vehicle for the U.S. Army. However, soldiers never used the Bell Rocket Belt due to its limited fuel storage and flight time. In 1965, the belt only had a 21-second maximum flight duration and a range of 393 feet. It was an intriguing idea with a flawed execution.

Although it wasn’t deemed military-grade, the Bell Rocket Belt opened up a new world to the future stuntman Bill Suitor. “Bill Suitor was an ordinary 19-year-old in 1964 when he mowed the lawn of Rocket Belt inventor Wendell Moore and put himself forward as a test pilot for the Rocket Belt in development with Bell Aerosystems,” says Meg Simmonds, archive director at Eon Productions, the U.K.-based production company that makes the James Bond films.

Suitor would pilot more than 1,000 flights with the Rocket Belt, including a demonstration in the opening ceremonies of the 1984 Olympic games. But perhaps the defining moment of Suitor’s career came when his job as a test pilot intersected with 007.

“Bond production designer Ken Adam thought [the jetpack] was just the type of gadget that Q Branch would issue James Bond,” says Simmonds.”

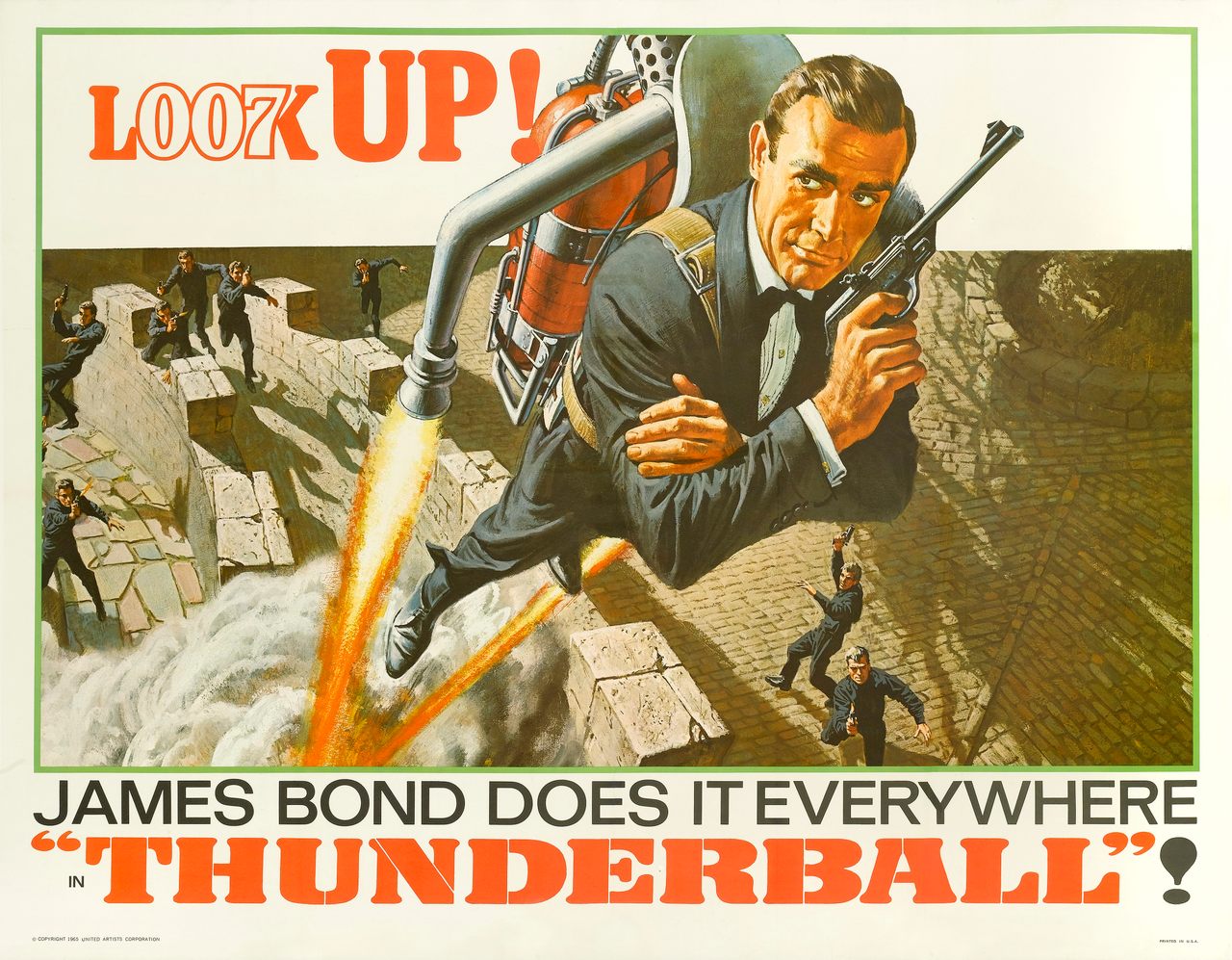

For the pre-title sequence in Thunderball, Connery’s Bond must kill Jacques Bouvar, an operative of the Special Executive for Counter-intelligence, Terrorism, Revenge, and Extortion (often abbreviated to S.P.E.C.T.R.E.). After killing the disguised Bouvar, Bond makes a hasty escape via jetpack.

To film the sequence, director Terence Young combined close-ups of Connery shot against a rear projection screen using a replica jetpack with long shots of Suitor actually piloting the jetpack.

Bond’s hurried getaway wasn’t merely a plot device. According to Robert Godwin, founder of Apogee Books, which published Suitor’s book, Rocketbelt Pilot’s Manual: A Guide by the Bell Test Pilot, Suitor sometimes joked that if a pilot was still 20 feet off the ground when the jetpack exhausted its 21 seconds’ worth of fuel, they were “going to have a bad day.”

“Eventually, they started putting an egg timer on the pilot’s wrist, which would go off at 20 seconds so they knew they had to get down,” says Godwin. “But pilots couldn’t hear the egg timer ringing over the jetpack. So, they replaced it with a vibrating device at the nape of the neck, which would start pounding your skull to tell you to get down.”

Fortunately, Suitor didn’t encounter any “bad day” problems on the set of Thunderball. Initially, the filmmakers were far more concerned with bad hair days. Even after a fight to the death and with seconds to escape, they wanted Bond to look cool and well-coiffed flying the jetpack helmet-free.

But, Suitor, who valued his head more than Bond’s meticulous side-part, arrived on set and donned his safety helmet. “The assistant director explained they had already filmed Connery without a helmet, so they tried painting the helmet brown to match Connery’s hair, but it didn’t look right,” says Bond archivist Meg Simmonds. “So, the whole production team, including Connery, had to reconvene to film Connery putting on a helmet to match what they shot with Suitor.”

The scene, shot at Chateau d’Anet just northwest of Paris, went well—but that helmet probably was a smart idea. “Suitor flew from the top of the chateau to the ground a few times—once bouncing backwards about four feet on landing,” says Simmonds, “but all flights were successful and all under the time limit of 21 seconds.”

Kathleen McCarthy, director of collections and head curator at the Museum of Science and Industry, says the Bell Rocket Belt, which is on loan to the museum from the University of Buffalo, has not undergone restoration for the “007 Science” exhibition. Unlike Bond, the jetpack flaunts its imperfections with a certain panache.

“It has all the beautiful scars of being used and operated,” McCarthy says. “It doesn’t look brand new, but it shows its history.”

In the exhibition, the Rocket Belt is displayed alongside a modern, commercially available jet suit from Gravity Industries, an intentional juxtaposition of Bond gadgetry with real-life, contemporary devices. The exhibition also includes Bond’s “suction cup climbers” from 1967’s You Only Live Twice contrasted with today’s Gecko Gloves.

“We’ve taken four Bond artifacts and paired them with contemporary technology to show that, while these items may have seemed like crazy ideas at the time, there were people out there developing these ideas,” says McCarthy. “Maybe it took a decade, maybe longer, but several of these items did eventually become a reality.”

The more modern iteration of jetpack technology that accompanies the Bell Rocket Belt, the Gravity Industries jet suit, is a fully functional device that can be purchased for about $400,000. The company also offers group flight experiences for $3,500.

“It’s a super cool fantasy—it plays into our age-old desire to fly like a bird,” says Daniel Levine, a trend expert who has studied jetpacks. “It’s different from being a passenger on a plane because with a jetpack you can have control and you can soar over the trees. That’s the ultimate dream. In fact, it’s a literal dream that a lot of people have.”

While the James Bond films have become known for debuting future technology, Levine acknowledges that the Jetsons-esque era in which we’re all rocketing to the office in our jetpacks has not yet arrived—and is unlikely to anytime soon.

“I think the challenges are just too insurmountable for this to be adopted on a wide scale,” says Levine, citing drawbacks like “safety, energy efficiency, control, maneuverability, regulatory issues, and environmental impact.” He says, “It makes sense for very narrow purposes, and I think that’s what we’ll see [jetpacks] being used for even more in the future.”

Levine added that although he has witnessed some military use of jetpacks, the current generation of this technology might lack the necessary stealth to carry out a military operation.

“I’ve seen them flying from ship to ship in the Navy, and the military might be able to find certain other uses for them,” he says, “but at the moment, jetpacks with conventional fuels are quite loud. So, you’re not going to sneak anyone over a border or anything wearing a jetpack.”

As much as Levine admires and respects modern jetsuit technology, he admits he’s relieved they won’t likely become a widespread part of his daily commute.

“Luckily, it’s not going to happen,” he says. “I don’t want to see people flying right past my window all the time.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook