Preserving the LGBTQ Legacy of One of America’s Most Historic Homes

Boston’s Longfellow House was a 19th-century refuge.

Think of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow—what comes to mind? High school English class? If you’re a fan, maybe “Paul Revere’s Ride” or “A Psalm of Life”? Beyond being one of America’s most famous poets, the twice-married Longfellow, who died in 1882, also holds an iconic and unlikely place in queer history.

Steps away from Harvard Square in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is Longfellow House, a stately Georgian home owned by his family (and eventually a trust they established) from 1843 to 1972. It was a home, but also a gathering place for artists and thinkers, and something more. Its archives contain a trove of documents about LGBTQ+ history. Several members of the Longfellow family, including the poet’s brother, daughter, and grandson, were, as park ranger Kate Potter puts it, “not straight.” Luckily for historians, they all left behind records of their lives in the form of letters, diaries, journals, articles, and photographs.

In more than 150 boxes of historical documents, modern scholars are uncovering the queer stories of 19th-century Boston’s intellectual and artistic high society.

The stories of LGBTQ+ people are not always easy to find. Modern historians usually learn about past lives through material they leave behind, such as letters and diaries. That’s only for people in certain places and times, of a certain education and social class, and within them, language about sexuality was often coded for safety. “We never know what conversations people had across the breakfast table or going for a stroll around the garden,” Potter says.

The butter-yellow Longfellow House, which also served as George Washington’s Boston headquarters during the American Revolution, is surrounded by formal plantings of roses and a neatly manicured lawn for those strolls. Inside, the house is filled with oil paintings, brocade and velvet textiles, dark wood bookshelves with piles of old books. A visit—in 1972 the house was donated by the Longfellow House Trust to the National Park Service, which offers a variety of tours—is a feast of sumptuous artifacts that immediately recall the upper-class history of the home.

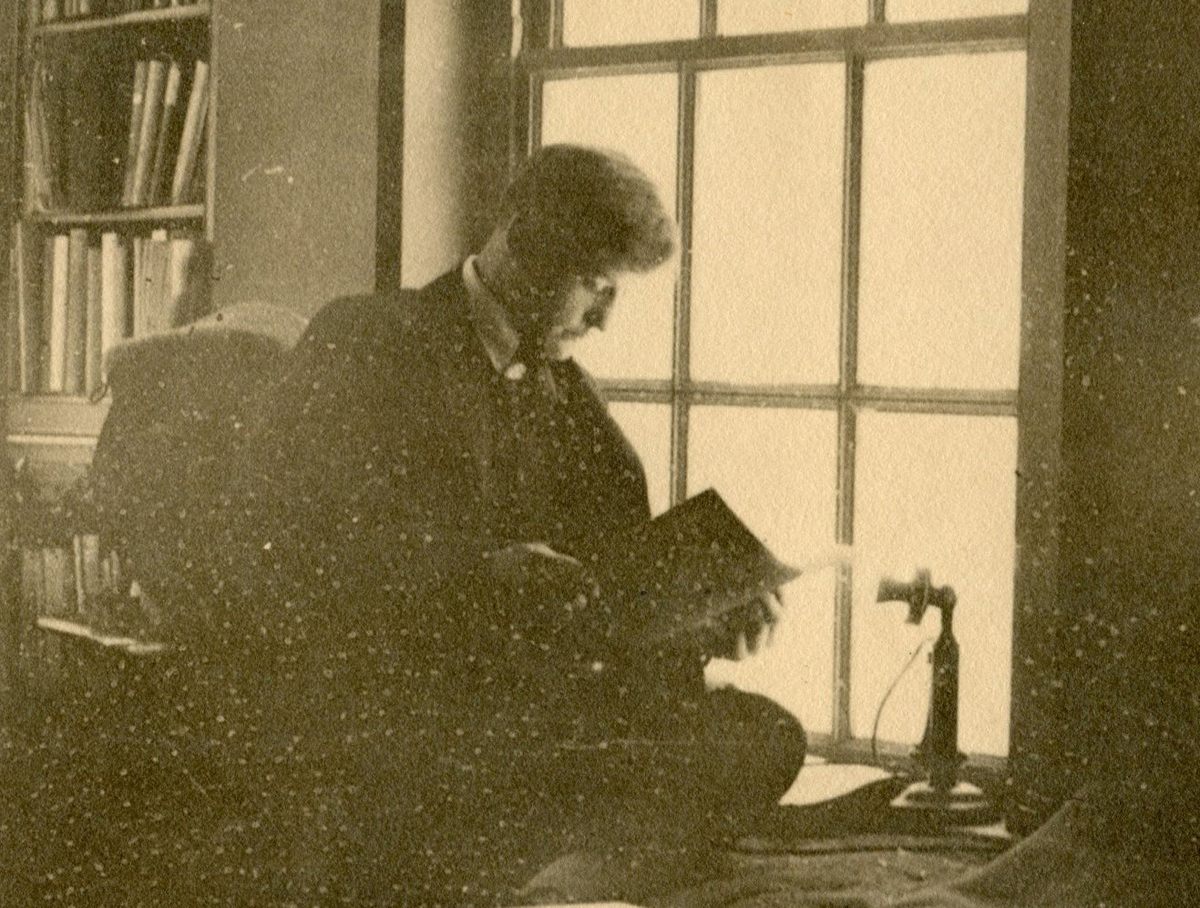

Arguably some of the most valuable objects in the Longfellow House are decidedly less lavish: the hundreds of journals of meticulously preserved sheets of paper and journals in the archives. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s well-educated and politically active grandson, Henry “Harry” Wadsworth Longfellow Dana, served as his family’s de facto archivist (when he wasn’t busy being a socialist or losing his teaching job at Columbia due to his pacifist political views). Thanks to Dana’s work preserving his family’s letters and journals, archivist Kate Hanson Plass has uncovered glimpses into the LGBTQ+ culture of historic Boston.

Take the poet’s youngest brother, Samuel, for example, a Unitarian pastor who died in 1892. “There are a few journals that contain pretty clear descriptions of same-gender attraction in Samuel Longfellow’s papers,” says Hanson Plass. “In his college-age journals, he writes very clearly about being attracted to and loving fellow students … of course, the all-male Harvard students.”

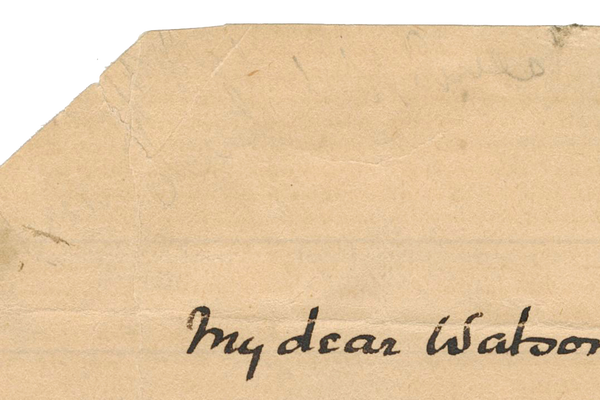

Alice Longfellow, the poet’s daughter, is known to have had a decades-long intimate relationship with a woman named Fanny Stone. An 1884 letter from Stone to Longfellow describes the emotional loss of a beloved piece of jewelry. “Fanny writes to Alice, ‘I have been wearing this bracelet that you gave me, and it never left my wrist. But I was on a bridge over the Potomac, and I took my glove off, and the bracelet went flying into the river,’” says Hanson Plass. Stone wrote that she felt like a widow when she lost the bracelet. “It’s really hard to argue that that is a platonic relationship.”

In addition to his tireless work to preserve his family’s history, Dana’s own journals describe his attraction to other men. “In his lifetime, 1881 to 1950, [Dana] was relatively open about being gay,” says Hanson Plass. “There is clear evidence in the papers that he had intimate encounters with men.” She notes that there is active research on Dana’s papers, with a focus on his time in New York City. “The men that he’s interacting with in New York are not from this elite Boston Brahmin society,” she continues. “He’s going to New York and he’s picking up mainly younger men, men with immigrant backgrounds.… We have an opportunity to dive into a little bit of that story and learn more about who they were as individuals.”

In their tours, the park rangers describe scenes of lively social gatherings in Longfellow’s living room, no doubt characterized by political and literary conversations. In addition to members of their own family, the Longfellows hosted and befriended prominent figures from Cambridge and beyond, including some known members of the LGBTQ+ community. For example, in January 1882, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow had Oscar Wilde over for breakfast. According to Potter, the two men had their disagreements when it came to literature, but “from what I understand at that meeting, they both left it thinking, ‘Gosh, that was much more pleasant than I was expecting it to be.’”

Novelist and friend of Alice Longfellow Sarah Orne Jewett was another regular visitor to the home and lived in a “Boston Marriage” to poet Annie Fields. A Boston Marriage refers to two wealthy women cohabitating without men. Some, such as Jewett and Fields’s, are thought to have been romantic. Jewett’s South Berwick, Maine, home is a Historic New England property, maintained by historians dedicated to illuminating the love between the two women. “Annie is mentioned in every room in the house. They talk about Sarah and her sexuality quite a bit,” says Potter. “They talk about Sarah’s journal, and how from a very young age she did not write about any crushes on young men. She wrote a lot about her feelings for other young women.”

When talking about the lived experiences of historical figures, Hanson Plass and Potter note that it can be tricky to apply modern labels to people in the past. “We don’t know how these people would have labeled themselves,” says Potter. “It might have been, ‘I have these feelings, but I don’t know where they come from or what that means about me.’”

Potter points out, however, that modern language helps us better understand the past. “Language is always evolving. It’s very much about looking back, but it is also about looking forward and seeing where we are right now in 2023,” says Potter. “I mean, who knows what it’s going to be like doing this in 2024 or 2033?”

The ranger and archivist also recognize the uniqueness of these archives and are quick to point out that the experiences of individuals associated with the Longfellow family do not necessarily reflect the experience of queer people broadly in the 19th and 20th centuries. “We have this very specific story at our site,” says Potter. “All the people associated with our site are white, and so far as we can tell, cis, and very privileged.

“We cannot tell the queer history of the 19th century.”

Though the subjects are a privileged few, there is still power in the stories. “There have always been queer people and certainly there have always been activists and there have always been people just quietly living their lives and existing in social units with their special someone,” says Potter. “Whoever that someone was.

“Queer people, or non-straight people, have always existed. There are certainly painful stories of people feeling isolated, but there are also these moments of connection where people found common ground.”

* Correction: The original version of this story incorrectly placed Squam Lake in Maine, not New Hampshire.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook