How the Internet Changed the Meaning of ‘Mamihlapinatapai’

An untranslatable word used among the few members of the Yaghan tribe has attained an odd sort of online fame.

“A look shared by two people, each wishing that the other would initiate something that they both desire but which neither wants to begin.” Okay, now say that in one word.

Hard to distill, isn’t it?

But one word does exist to define this nebulous concept, a term originating from the highly endangered Yaghan language: Mamihlapinatapai.

Listed in the 1994 Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s most “succinct word,” mamihlapinatapai stems from the language of the Yaghan (or Yamana) tribe of Tierra del Fuego, an archipelago split between Chile and Argentina at the southern tip of South America.

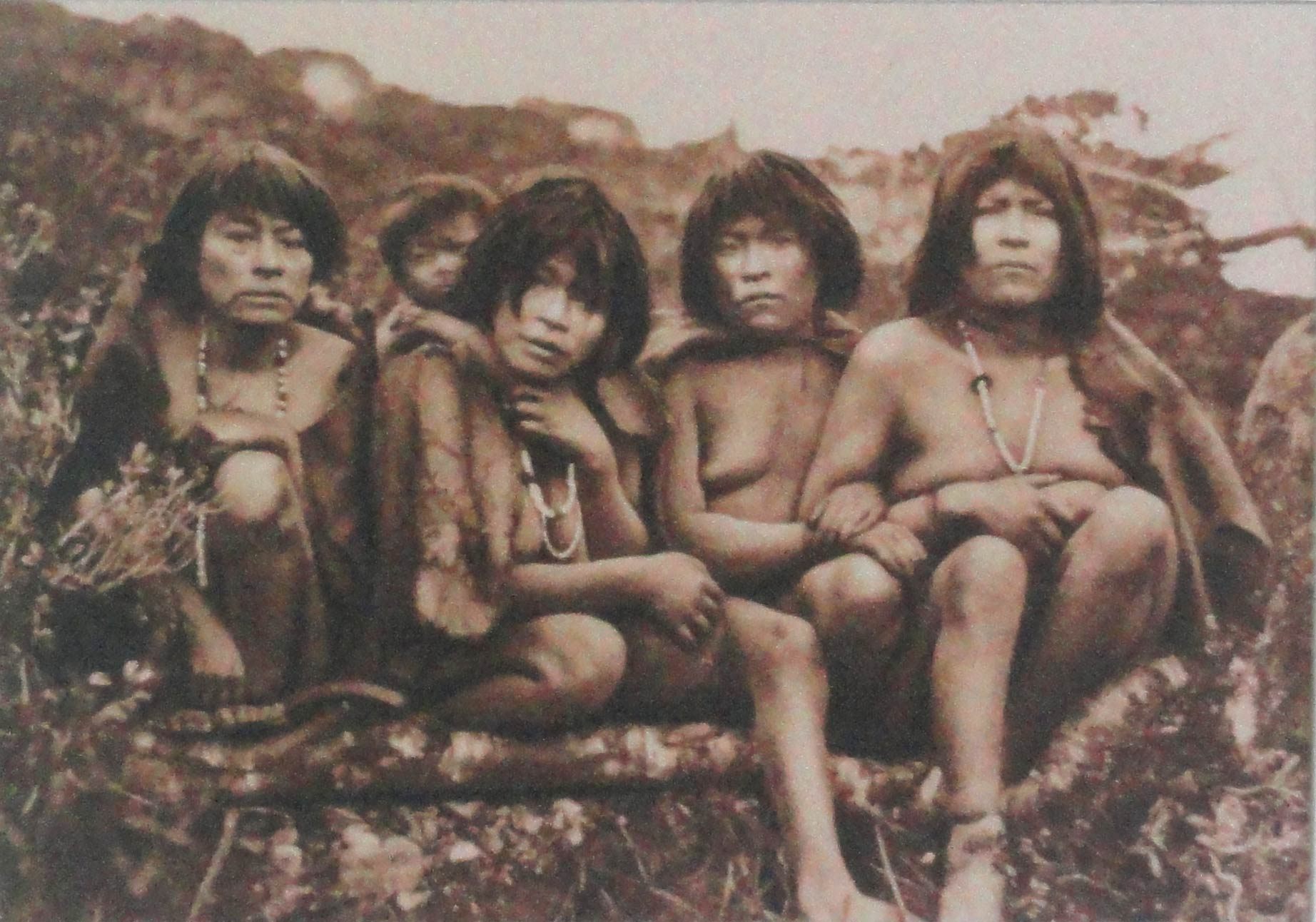

The Yaghan (or Yamana, as they are also called) have lived as hunter-gatherers in Tierra del Fuego for more than 10,000 years. They are nomadic, and their language, rich in words describing the sea and marine life, links them to their land and culture. Today, the tribe has been reduced to fewer than 2,000 members. Most speak Spanish.

Routinely considered to be one of the hardest words to translate, “mamihlapinatapai” has nonetheless found a place among the world’s favorite “untranslatables”: words that communicate concepts or situations that lack exact definition in English or other common tongues.

Mamihlapinatapai first started appearing consistently on websites globally in the late 2000s. It has since infiltrated the worlds of art, pop culture, and Internet subcultures related to linguistics and creative writing. One reason for its popularity may have been its mention in the 2011 documentary Life in a Day. Composed of crowdsourced video clips portraying a day in the life of people all over the world, the film, according to director Kevin Macdonald, is “a metaphor of the experience of being on the Internet … clicking from one place to another, in this almost random way … following our own thoughts, following narrative and thematic paths.” In response to the question “What do you love?” a young woman, standing in the forest, speaks into a handheld camera, describing the word mamihlapinatapai, giving its origin, various definitions, possible pronunciation, and explaining what she loves about the phrase.

Apart from the lost-in-your-eyes romantic notions that most people associate the word with, mamihlapinatapai has also been cited in gamer’s theory as referring to the volunteer’s dilemma, in which any of a number of players faces a decision that may require a sacrifice on an individual player’s part, but will benefit everyone else.

In the art world, mamihlapinatapai has become an inspiration for a variety of artistic mediums, including serving as the title of a song on American actor and musician Ronny Cox’s 2004 album, and the title of an exhibit by Belgian photographer Max Pinckers. It has influenced artwork, stories, essays, videos, and books, such as the popular Lost in Translation, in which author Ella Frances Sanders colorfully illustrated some the world’s favorite untranslatable words. Some people have even inked themselves with it. Mamihlapinatapai has also wormed its way into academia, being featured in the book Defining the World in reference to Samuel Johnson’s—of A Dictionary of the English Language fame*—tribulations in finding compact but accurate definitions for words, and in a 1998 sociology treatise entitled “Social Dilemmas: The Anatomy of Cooperation.”

“I think the word and its approximate translation is popular because most people can relate to that awkward, fleeting feeling of wanting to initiate something meaningful, but not wanting to be the first, for fear of embarrassment or rejection,” says Anna Daigneault of the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages, a non-profit that works to document threatened languages. In recent years, the organization has done a lot of work with tribes in Chile and Tierra del Fuego, where the Yaghan tribe originated and currently live, and where many native groups are losing their linguistic heritage, deferring to Spanish over tribal languages. This is due to dwindling numbers—the 2002 census counted 1,685 Yaghans—the pressure to speak the native language of the country they live and work in, and societal bias against indigenous groups.

However, Daigneault also brings up the fact that, outside of its parent culture, mamihlapinatapai is being viewed and interpreted differently from its original meaning.

“I think through a Western lens, it might appear that this word has a romantic undertone, but it might not be used in that way in the Yaghan language,” says Daigneault. Rather, it may be closer to “a strong, shared glance that connects the two speakers in some way that is beyond words.”

While mamihlapinatapai is undergoing its own online renaissance and reinterpretation, its parent language is on the brink of extinction.

The Yaghan lexicon is a language isolate, meaning that it has no linguistic relatives. It is an idiomatic island. If it dies out, there are no related languages that conserve elements of the language.

As is the case with many indigenous groups throughout history, when European settlers came to Tierra del Fuego, their diseases and land-grabbing decimated local tribes. As of 2017, there is only one fluent, living speaker of the language left: 89-year-old Cristina Calderon. When “Abuela”, as she is lovingly referred to, eventually passes away, much of the language and its connection with the Yaghan culture will die with her.

But there is still some hope. Calderon has taught her granddaughter, Cristina Zarraga, some of the language, and both Calderon and Zarraga have published several books for posterity about Yaghan culture and history, as well as stories from Calderon’s own life.

Furthermore, the Yaghan language has been preserved in dictionary form, and can be found at such august institutions as the Library of Congress. The Yahgan Dictionary: Language of the Yamana people of Tierra del Fuego exists thanks to Thomas Bridges, a missionary who lived in Tierra del Fuego in the late 1800s with his family and worked with the local Yaghan people, recording their culture and language for more than 20 years.

But even so, as anthropologist Maurice van de Maele wrote in an article for the Chilean newspaper EMOL, “the younger generations also know the Yagán language but not at Cristina’s level, so there will be an irreparable loss.”

Also, while mamihlapinatapai’s Internet fame has introduced the world to its parent tongue and culture, it has also brought unwanted media and tourist attention to the Yaghan community, which has closed ranks against the intrusive outside world and rarely offers glimpses into their lives.

Has exposing the world to the Yaghan language through mamihlapinatapai been enough to spur interest and potentially save the language? Linguists and experts say no.

“A ‘living’ language is one that is still in use by the generations in its speech community. So no, if only one word survived, that does not mean the language is still alive. The fame of that one word may still provide a little bit of visibility on the internet, and thus a bit of effect on the mass consciousness,” says Daigneault. “But it’s more of a ghost whisper at that point.”

* Correction: This story was updated because it incorrectly associated Samuel Johnson with the Oxford English Dictionary. Johnson compiled A Dictionary of the English Language some 170 years earlier.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook