How a Master Maze Maker Gets You Lost

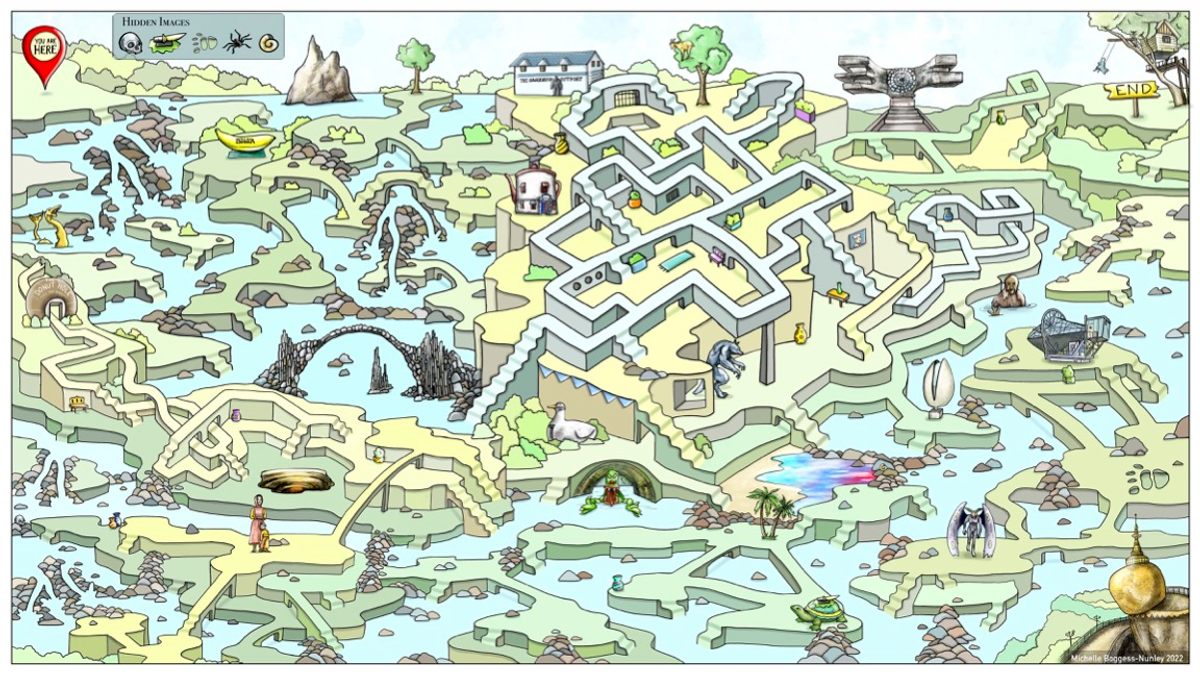

Michigan-based artist Michelle Boggess-Nunley has created a new, Atlas Obscura–inspired challenge.

Michelle Boggess-Nunley moved from an office job to life as a professional artist a few years ago, which led her back to a childhood passion: hand-drawn mazes. The Grosse Pointe, Michigan-based artist now holds the Guinness World Record for the biggest hand-drawn maze—around 1,500 ft long, so large that it had to be photographed panoramically, wrapped around a soccer field, for the final submission.

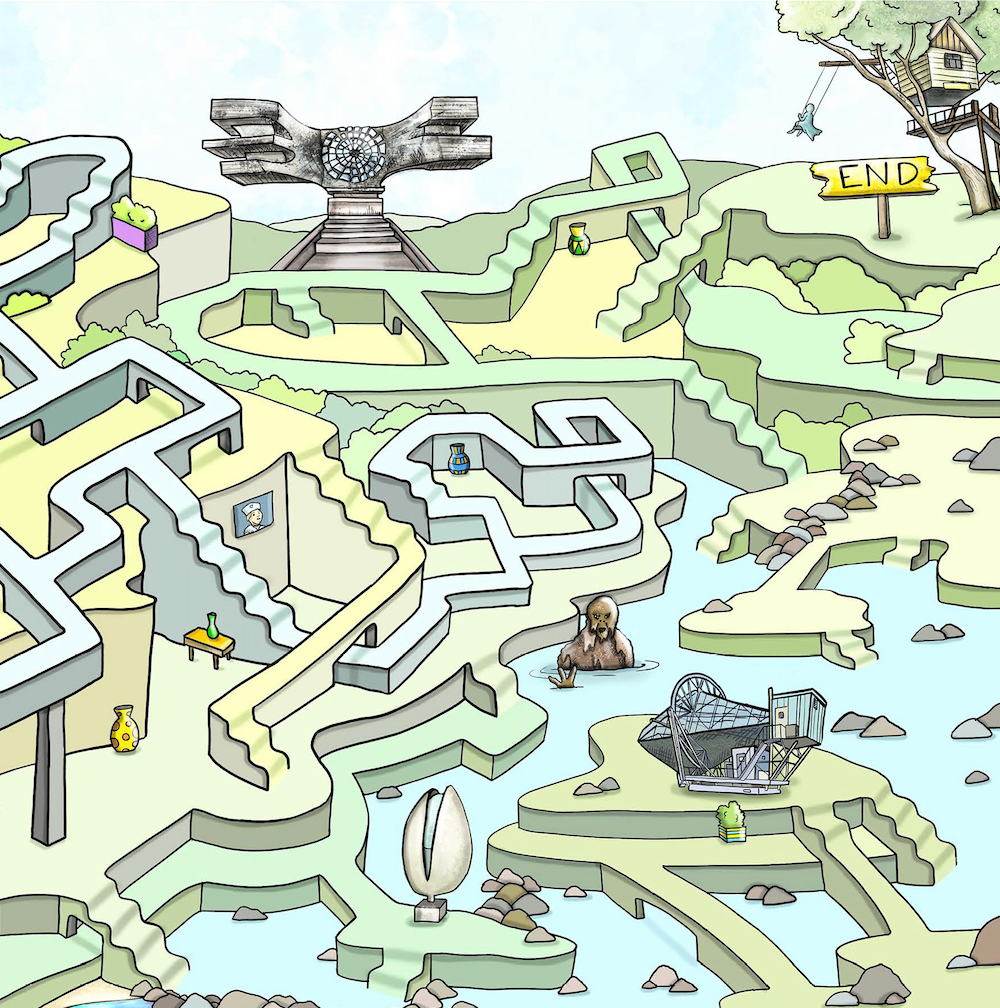

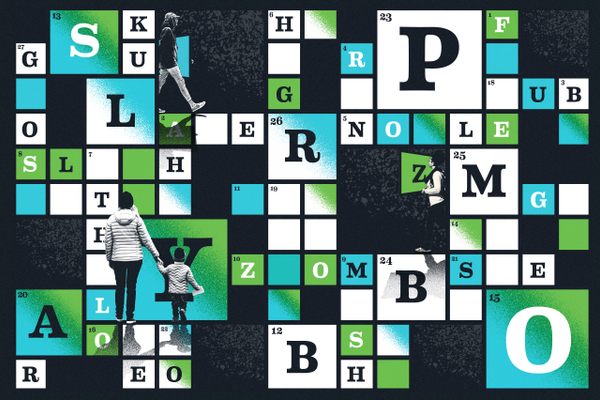

Since putting out her first book of mazes in 2019, Boggess-Nunley’s worked on multiple other books (including A.J. Jacobs’s new book, The Puzzler), exhibitions such as ArtPrize2021, and commissions, including a wall mural maze outside a local restaurant. So we tapped her to create a downloadable new maze for Atlas Obscura to help us launch our new puzzles, based on some of the wondrous locations we feature—all of which are clickable in the downloadable PDF.

We spoke with Boggess-Nunley about how she got into mazes, how you stay one step ahead of solvers, and what it was like to make a single maze—in public—for months.

How did you get into making mazes?

When I was in second grade or third grade, my mom let me get one of the Highlights maze books. I was obsessed. I solved them from front to back, finish to start. And then I just memorized them. And then I thought, I could start making my own mazes, so I made a maze book for the entire third grade class.

How did you go from that to making mazes professionally?

There was a long period where I didn’t make mazes at all, maybe 10 years or so. But I’d always solve mazes. I remember drawing my first maze after getting back into it—I was probably 18, 19 years old at that point—and I remembered how much I loved it.

So, one day I’m like, “You know what? I’ll make a book.” I was transitioning from the corporate world. I was a court reporter and went into being an artist full-time. And mazes were that little puzzle piece that was missing. I did a couple children’s maze books and some coloring books with mazes.

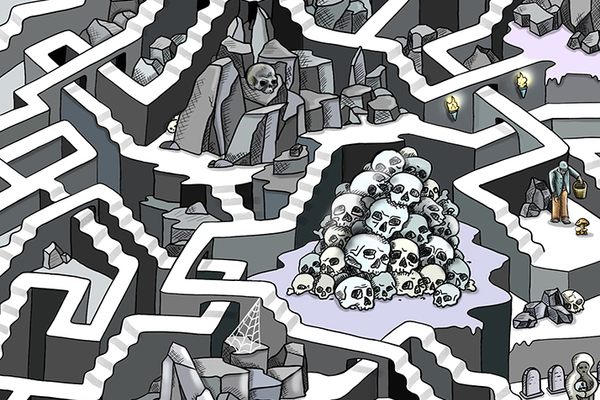

Then, during the pandemic, we had that period where nobody was working, especially if you were in the service industry or doing anything with people. And the days went on, the weeks went on, the months went on. I run a little art studio on the side. I teach children and seniors how to draw and paint, and there was none of that going on because the fundraisers weren’t happening for these organizations. So I had the idea of doing a really big maze to raise money for the organization Detroit Living Arts.

How did you go from making a big maze for charity to breaking a world record?

At first it was something that was just going to be fun: We’re going to sit in a gallery window and make this giant maze and people are going to get involved and we’re going to raise money. But then I got connected with a lot of other maze artists. We’re a real niche art form. There’s only maybe a handful of us that do this in the whole world, and every year we make a book together. Two of them are official world record holders, Joe Woes and Eric Eckert. All the pieces just kind of fit together: I can beat the world record, I can raise money for this cause, just burn some time, and make a giant maze.

What’s the process of actually getting a world record confirmed? It sounds like it could be complicated.

When I applied, they gave me a full book of stipulations that I had to follow or I could be disqualified. Drawing the maze was only half the challenge. I think the guidelines are probably the hardest part. Because we were in the middle of the pandemic, things were exacerbated. The maze had to be done in a public place, and they were hard to come by. And they required me to have two witnesses that had to watch the entire process of me drawing. It had to be done for four hours a day. The witnesses had to log in and log out every day.

I found a local art gallery down the street from my house with a really nice front window, Posterity Gallery. The two witnesses were the owner, Sherry McInerney, and the manager, Sherry Allor. Guinness wanted every second of the process video-taped, so I had to get two cameras set up just in case one camera stopped working. I ended up having a whole army of people behind me helping me.

The entire maze had to be solved, which presented the biggest challenge. Solving it probably took just as long as drawing it because there were very intricate paths. The path could only be one centimeter in thickness, so that was another challenge.

People were allowed to come in and ask questions. I did a lot of doodles inside the maze path—that’s how we raised money for Detroit Living Arts. People could sponsor a square foot of that maze, and they could request doodles—portraits of their dog and their kids and symbols. That probably took longer than the actual maze itself. But it was really fun watching people get involved.

How long did it take?

It took three months and 10 days, which ended up being just under 300 hours.

I’d estimate only half of the time I spent was actually drawing the maze itself. The doodles took a lot of time, with more than 300 names, doodles, and hidden images. The other time-consuming part was solving the maze as I went. There was no skimping on any of the complexities to finish quicker, because all the while I had hoped that someone would attempt to solve it.

How did it feel to finish?

It was actually kind of bittersweet. Though part of me was happy to move on to other projects, there was also a layer of sadness. I had made so many friendships along the way. The maze became more about staying connected and getting people involved than breaking a record. There was also this overwhelming sense of gratitude, because I knew this was something that took an entire village to see all the way through. Every obstacle that seemed impossible to overcome, and there were a lot, I was fortunate enough to have a community of people to help me get past it. From the public space to create it in the middle of a shutdown, then finding willing witnesses, to the land surveyors that volunteered to measure it, to the venues that donated their space for measuring, then the videographers that helped raise awareness to the cause, right up to the photographer for the final photograph that Guinness required for the title, and then finding an indoor space large enough to unroll it in. The list is infinite. None of it was easy, but there was so much support behind me at every stage of the process.

How do you come up with and design a maze?

It’s like a maze up here [points to head]. For me, it’s almost a calming effect. When I’m making a maze, I feel clearer I than I ever do. It’s like everything makes perfect sense.

Making a maze is not just designing it. You’re looking into what’s going to happen: Where is this path going and what is it going to connect to? So you have all these different paths going simultaneously and you try to get into the mind of the solver, because people are going to cheat. They’re going to want to start from the finish. I try to think of little tricks I can do, like maybe I’ll put in a fake path. It’s this constant conversation I’m having with myself, trying to figure out what the solver is going to do and trying to design around it. It’s almost like you have to be the solver and the designer when you make it.

How did that work for the Atlas Obscura maze?

I love Atlas Obscura—all the wonders and the crazy, weird places in the world. I went into a hole researching all these things. I picked the places and stories that really stuck out to me, like the goats in trees in Morocco.

It had a twist, because some of the places in Atlas Obscura were in water, some were in caves. I had to show different landscapes. So I did it in an isometric way—like a three-dimensional drawing where it looks like you’re coming in from an angle. It worked well for a lot of the buildings and sites that I included.

What’s the most rewarding part of making mazes?

Having people solve them and get through them is probably the most rewarding for me. I’ve got a 10-year-old, and he’s my go-to guinea pig. I make a maze, and just watching him solve anything, I get excited. I’m always rubbernecking, making sure he’s not cheating! [Laughs.]

How long does it usually take people to solve one of your mazes?

It depends on the maze. There’s not a whole lot of mazes out there that are made for adults. I think it’s an art form that hasn’t quite been tapped into yet, but it definitely has a place in the puzzle world. I feel like this year something is different. It’s the time for puzzles. It’s the time for mazes, whereas a few years ago, you didn’t really see a whole lot of this before.

Do you think the pandemic has pushed people toward these more analog pleasures?

Definitely. You know, I hear a lot more about puzzles and shows popping up all over the place. It’s fun to see. There’s this whole movement happening now.

Mazes have always been here since the beginning of time, in labyrinths, though they’re not technically mazes, and mythology and other forms. But now it’s accepted as something that’s challenging and improves your cognitive skills. I think now finally people are accepting it as one of their other daily puzzles, like they would like a crossword or a sudoku.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook