‘Mind-Blowing’ Archaeological Find: Wooden Prosthetic for a Medieval Foot

An iron ring, likely used to stabilize a wooden prosthesis, was found in situ. (All Photos: Courtesy Österreichisches Archäologisches Institut (Austrian Archaeological Institute))

There are at least a few reasons to go to Hemmaberg in southern Austria. Christian pilgrims flock to its cluster of lovely stone churches. The sick seek the alleged healing powers of its thermal hot springs. Archaeologists—they go for the graves.

Since 1978, hundreds of skeletons have been found at the site in the Karawanken foothills and a few years ago, excavators at Hemmaberg unearthed a small group of burials, mostly children, in a cemetery from the early medieval period. Among these graves, one stood out. It was a burial of a middle-aged man who died in the 6th century A.D. He was laid to rest with a short sword and a brooch and his skeleton was fully intact except for his left foot and ankle, which had been replaced with a prosthetic device.

A close-up of the iron ring.

“When I saw that they had this prosthesis, I thought, ‘OK, this is something special,’”said Michaela Binder, a bioarchaeologist with the Austrian Archaeological Institute. “It is always a surprise to find something like this simply because it was so rare.”

The surviving evidence, scant as it may be, shows that humans have been using prostheses for thousands of years. Some Egyptian mummies have been found with replacement toes made from wood or cartonnage. The oldest known example of a lower-leg prosthesis dates back to 300 B.C. and was found in a Roman grave in Italy’s Santa Maria di Capua. Made out of a wooden core coated in a bronze sheeting, it was excavated in the 19th century but unfortunately destroyed in a World War II bombing.

There is actually little left of the 1,500-year-old prosthetic device found at Hemmaberg. The wood has deteriorated, and all that remains is an iron ring, barely over three inches in diameter, to stabilize the device. There is also a dark staining on the lower leg bones, perhaps left from a leather pouch used to strap the prosthesis to the man’s leg. Besides preservation challenges, there’s another reason that few prosthetic devices survive in the archaeological record: It was tough to survive grisly amputations in pre-antibiotic times.

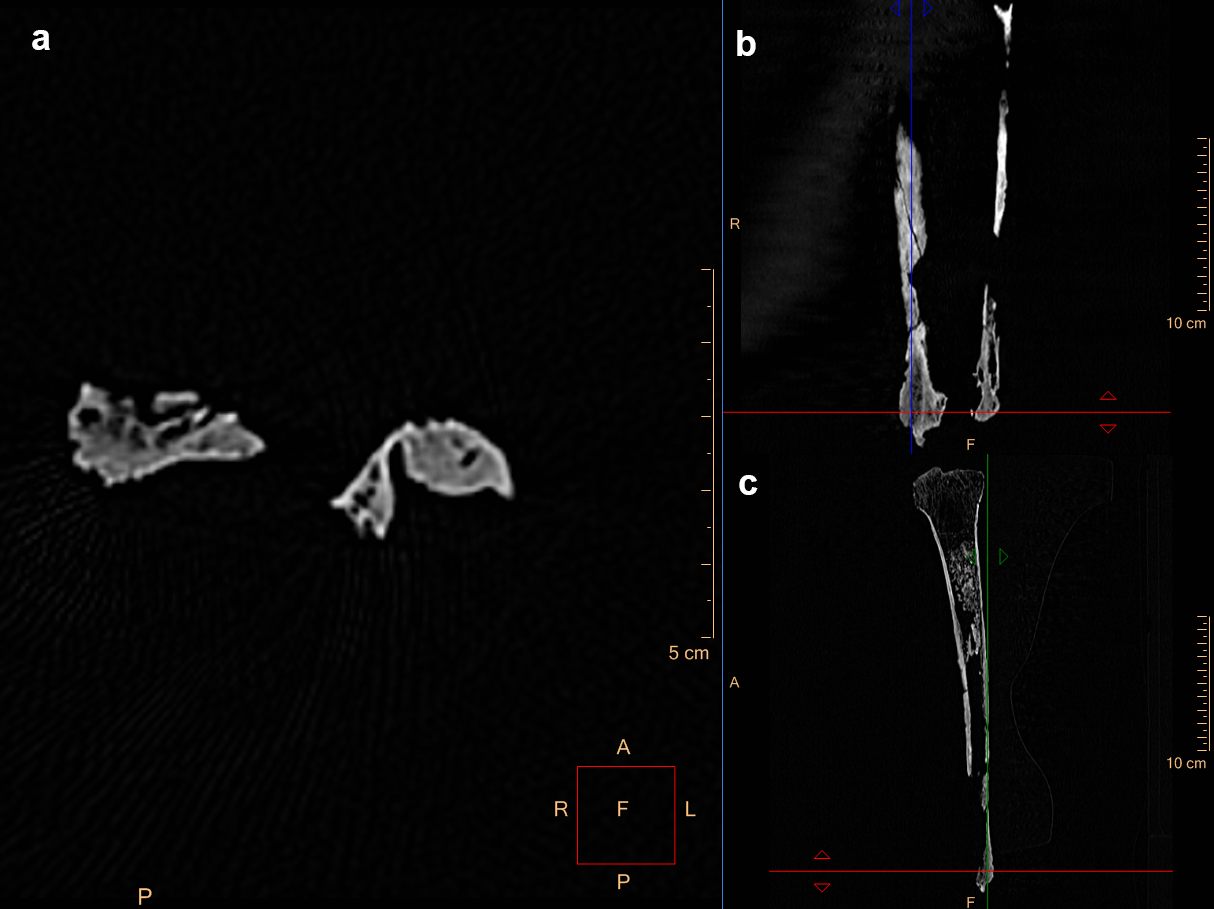

The skeleton of the man, with his left foot and ankle clearly missing.

“Losing a foot—and especially when it’s not cut through the joint but through the bone—would have lacerated a lot of blood vessels and caused an extensive amount of bleeding,” Binder said. “It would have very prone to infection. This is probably another reason why we see so few prostheses or amputations. Most people simply died quite quickly afterwards. So, finding an injury like that healed and finding ways that allowed the person to function at that time period to me is always mind-blowing.”

The man’s tibia and fibula had been cut to amputate his left foot and ankle.

Binder’s analysis of the bones, which was published last month in the International Journal of Paleopathology, found differences in the bone density of both legs, indicating that the man’s left leg was immobilized at least for some time. But it’s not clear why this man needed his foot and ankle amputated in the first place. Once the edges of the fracture are healed, it’s impossible to see traces of cut marks or sawing marks. (Recent studies have shown that it only takes eight to 10 days until these traces are completely grown over by new bone again, Binder said.)

An X-ray shows the amputated ends of the man’s tibia and fibula.

The limb could have been lost in an accident (perhaps horse-related—the man’s hips and knees have the signatures of habitual horse-riding) or possibly removed in an act of violence. In antiquity, amputation was sometimes used as a form of punishment. (A 1700 B.C. pit filled with cut-off hands was recently found at Tell el-Dab’a in Egypt.) But this last scenario is unlikely, Binder said. The man seems to have had a high status in his community, as his grave was within or close to the church, and he was buried with a sword. For a high-ranking person to pay for a crime with his foot would have been highly uncommon. For that man to then get a prosthesis seems even more unlikely.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook