The Life and Fiery Death of the World’s Biggest Treehouse

Its dedicated, sagelike maker isn’t at all upset.

For the thousands of people around the world who’d once visited and admired the world’s largest treehouse in Crossville, Tennessee, the news came as an awful shock. In October 2019, a blaze consumed the singular construction. But for Horace Burgess, the treehouse’s architect, this is just how things go. He was well acquainted with how it feels to lose your own, self-built treehouse in an angry conflagration. Heck, he’d already burned one down himself.

“It was just evil,” says Burgess of the older treehouse he built and then razed back in the 1980s. There was “no good about it.” The house had ended up serving as Burgess’s hideaway for doing drugs, which he committed to quitting after the deaths of some friends. Trouble was, the house itself had become part of the habit. A voice came to Burgess, saying that he had to burn the house down if he was going to rebuild his life. And it wasn’t just any voice.

People typically think “you’re a little bit crazy when you say that God spoke to you,” Burgess admits, “but really he’s the one that tells us to put our pants on in the morning.” Looking back, Burgess says that burning that first treehouse down—on God’s advice—was “probably the most sane moment in my life.”

Having freed himself from the demons trapped in that treehouse, Burgess, a pastor who grew up in Crossville, set about dedicating his life to religion and his community. Ironically, those commitments quickly brought him right back to building treehouses. After all, he knew he could do it well, and he understood that if he could share it with others it could serve as a positive force in the community rather than as a destructive force in his private life. “It was just something I enjoyed doing,” he says, seemingly uninterested in understanding why. As an aside, he mentions casually that he’d actually completed five or six treehouses in total by that point in time—even if people only ever seem to talk about the one that was about to come.

So, in 1993, Burgess got down to work on his family’s farm—139 acres that, according to Burgess, once contained a “zoo” with two of each animal, like a landlocked Noah’s Ark in central Tennessee. Not knowing where things would lead, he simply started by building a staircase, one he actually called the “Stairway to Nowhere.” It was more meditative than anything else. “I had totally turned my life over to the lord,” he says, and inspiration struck one day when he was actually “sitting down and praying for anything but a treehouse.” It was then that “the Spirit of God quickened me,” he says, and Horace Burgess gave in to the treehouse impulse and resolved to turn the Stairway to Nowhere into the world’s largest arboreal construct. And why not the largest? God had promised Burgess, after all, that he would never run out of material as long as he kept building, and building, and building. It sounds Old Testament stuff.

“I’m getting ready to build the world’s largest treehouse out here,” Burgess told his neighbors after the revelation. Half-informing them of his decision, half-asking for their permission, he understood that the undertaking would impact the whole community. “Someday you’ll have to watch when you pull out of your driveway,” he told them. They told him to go for it, though he suspects that “about 12 years later, they were wishing they had never agreed.”

For the next dozen years, Burgess just kept building. Higher and higher, wider and wider, until, plank by plank, nail by painstaking nail, he had single-handedly built a mansion extending 97 feet into the air. The numbers—a quarter-million nails, for example—are just one way to appreciate the scale of Burgess’s achievement. With such a monumental product at the end, it can be easy to overlook the daily grind, the unromantic resourcefulness that turned his inspiration into reality.

Burgess says he “tore down barns and outbuildings, and people would have different kinds of places that they would want me to clean up” in exchange for the dislodged materials. This ongoing bartering process allowed Burgess to state that the entire treehouse was made of recycled wood, and with other kinds of recycled materials. And, thank God for that. Burgess says that over the course of the 12 years of construction, the cost of nails more than doubled.

He never stopped, never doubted the project, never got hurt beyond small cuts from nails here and there. He says he saw it like his own personal Field of Dreams, encouraged by the conviction—“without a shadow of a doubt”—that if he built it, “they” would come. Indeed they did. Once Burgess put a roof over the treehouse and opened it to visitors, in 2005, he was quickly welcoming guests from all over the country and even the world. Many simply caught chance glimpses of the treehouse as they passed through, many others planned road-trips specifically to see it. Still others, says Burgess, flew in from as far away as England, France, and Guatemala, among other places. Couples even started lining up to get married in the treehouse, and Burgess told The New York Times that he officiated some 23 weddings there. On account of Burgess’s vocation and the elevated aura, the site came to be known as the Minister’s Treehouse.

Those who made it to the treehouse, even years ago, still attest to its grandeur, as if it was an icon of ancient architecture. “Looking up at it from the ground, I couldn’t get my head around the fact that one man had created this place all by himself,” says Chad Gallivanter, a videographer who visited the treehouse back in 2009, in a written message. “Just like architectural marvels of old, it was a modern-day example of human ingenuity and determination.”

Pete Nelson—a professional treehouse architect who has built more than 350 over the course of his career, and who hosts the show Treehouse Masters on Animal Planet—was similarly impressed. “As a builder,” says Nelson, “I was just really intrigued by how he managed to take what were clearly just leftover scraps and turn them into this edifice.” With first-hand knowledge of what goes into creating “something like that, and knowing it was just him,” all Nelson could say was, “Wow, this guy is the real deal.” Indeed, Nelson returned years later with a camera crew to shoot an episode of Treehouse Masters about Burgess’s creation.

And so, for years, Horace Burgess played the humble carnival barker, welcoming strangers into his mystical offroad apparition. That changed in 2012, when the authorities permanently shut down visits over safety concerns. According to Burgess, a retired engineer who had come by the treehouse wrote to the state that he “had seen some things that was unsafe,” leading to an inspection that resulted in the declaration of a public hazard. The state, says Burgess, wanted him to pay for new engineering work to be done to bring the treehouse up to code. Burgess wasn’t interested.

“Everything in it was unsafe,” Burgess admits with a laugh. “I see no way that you could make a 97-foot treehouse safe,” at least not in the legal sense. While no visitors had ever been hurt, Burgess didn’t fight the decision—just as he had done before, he simply let it go. He sold the property and returned to private life, his massive creation looming just down the road in majestic obsolescence.

Glenn Clark, the most recent owner of the property, told local television station WBIR that he had no intention of tearing the treehouse down, had no idea what caused the fire, and was upset about its destruction. Clark could’t be reached for comment.

Not everyone, however, was willing to let it go. Lindsey Turner, a graphic designer from western Tennessee, visited the treehouse years after it was formally closed, and trespassed onto the property in 2015. “I just love strange, relatively little-known, off places,” she says, likening the treehouse’s spirit to that of the “Mindfield” in Brownsville, Tennessee, a kind of physical diary documenting the life of the artist, Billy Tripp. The treehouse, she says, was “a living piece of art that was constantly changing. I just thought that’s something I’ve got to try to see”—even if that meant getting loose with the law.

She braved the condemned public hazard on her own, and wrote in a blog post that “I felt my stomach jump up to my throat as I thought about how I was two, three, four, five floors up on wooden boards that were constructed by a man with no blueprints”—a sensation not exactly quelled by the “widely spaced floor boards” that allowed her to look down and see just how high she had climbed. Still, in yet another nod to Burgess’s amateur architectural prowess, she says it all felt “surprisingly stable.”

The musician Lilly Hiatt, who visited the treehouse just in summer 2019, felt safe for reasons beyond the building’s structural integrity. She understood that Burgess “had so much thoughtfulness in his heart when he was making this,” and she could feel that. She “felt very comforted,” she says, “by the inspiration of it all,” adding that the feeling she had in the house was more intense than any she’s gotten inside a traditional church. “It felt very loving,” she says, and in turn she “didn’t feel too guilty about the trespassing.” It was clear from standing inside that Burgess “built this because he wanted people to see it and feel inspired by it, and that’s what I came here to do.” If she were caught, she figured, “maybe he’ll pardon me.”

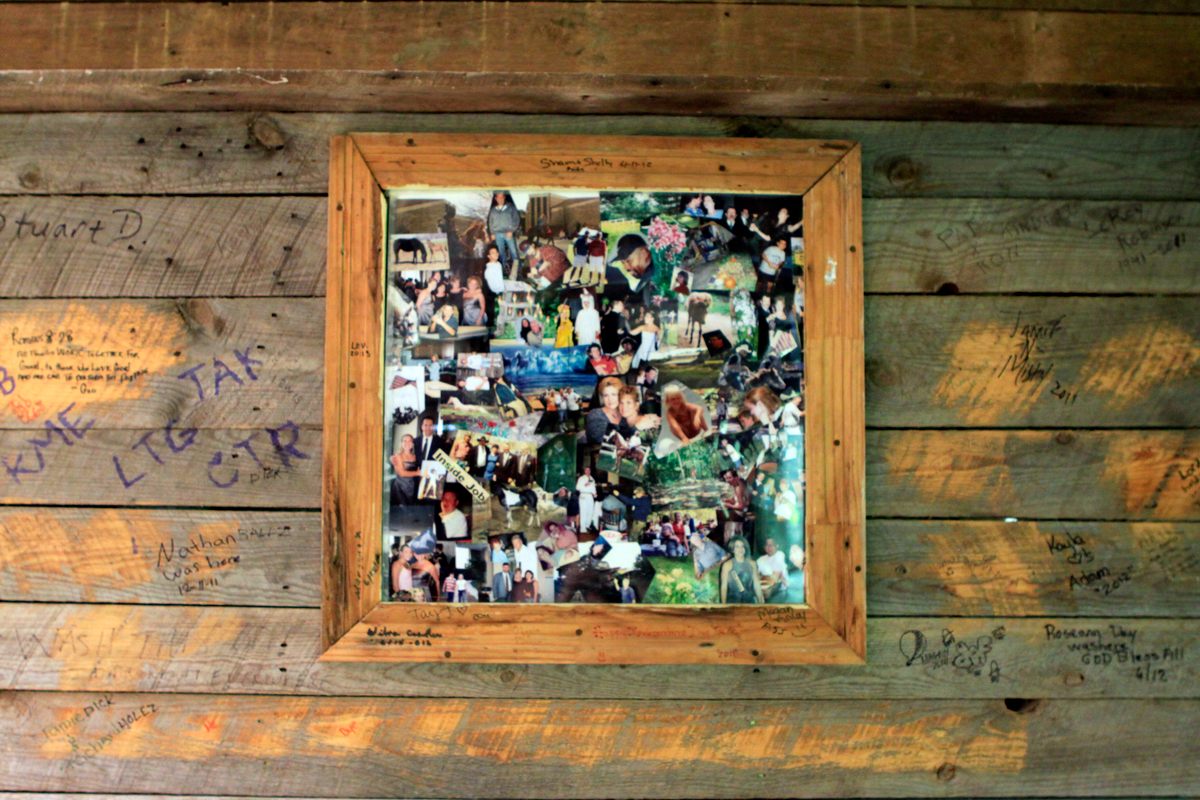

Each of these visitors remembers the treehouse for its sheer expansiveness and scale, physically and spiritually, the sense that it was somehow infinite unto itself. “Just when you thought you couldn’t go any further,” writes Gallivanter, “another staircase revealed itself.” Exploring it was a kind of journey through unrelated ephemera that combined to create their own world: furniture, appliances, statues of the 12 apostles, a basketball hoop, graffiti. At its center was an enormous chapel, replete with pews, a pulpit, and a large cross. “I couldn’t get over how massive this room was,” writes Gallivanter. “It was a testament to the man’s faith and what he valued in life.” Burgess thought it fitting to have a church in the trees: “There’s just something about being up above things,” he says, that makes it all “a little bit more tolerable.”

That peace of mind seems to have returned to ground level with Burgess, who met the treehouse’s demise with predictably sagelike stoicism. Fifteen minutes—that’s all it took for the flames to consign his masterpiece to memory. And we’ll probably never even know why: The weather was clear on that October night, and there was no electricity in the structure. Trevor Kerley, Chief of the Cumberland County Fire Department, says the current property owner declined to have the fire investigated.

It’s tolerable for Burgess, in part, because he had already lost something before losing the structure itself. What meant most to him about the treehouse was meeting “a lot of wonderful people” whom he would never have otherwise met—but those introductions essentially stopped when the site was closed.

Past visitors seem to be taking it harder, and in the initial weeks following the fire, Burgess says he was hearing from several people per day. “You don’t know how anything touches another person,” he says. “It’s just story after story of how people were blessed when they visited the house.” Hiatt says that her visit filled her with “a lot of hope,” with “realizing how compelled humans can be by a higher calling.” The Minister’s Treehouse didn’t charge admission, or propel Burgess to any sort of conventional fame. It just was—a defiant, aspirational, proudly strange manifestation of arbitrary inspiration. It “will now be the stuff of legend,” says Turner.

Don’t expect Burgess to tell you what, if anything, will rise in its place. “I’m just waiting,” he says, “on what God wants me to do next.”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook