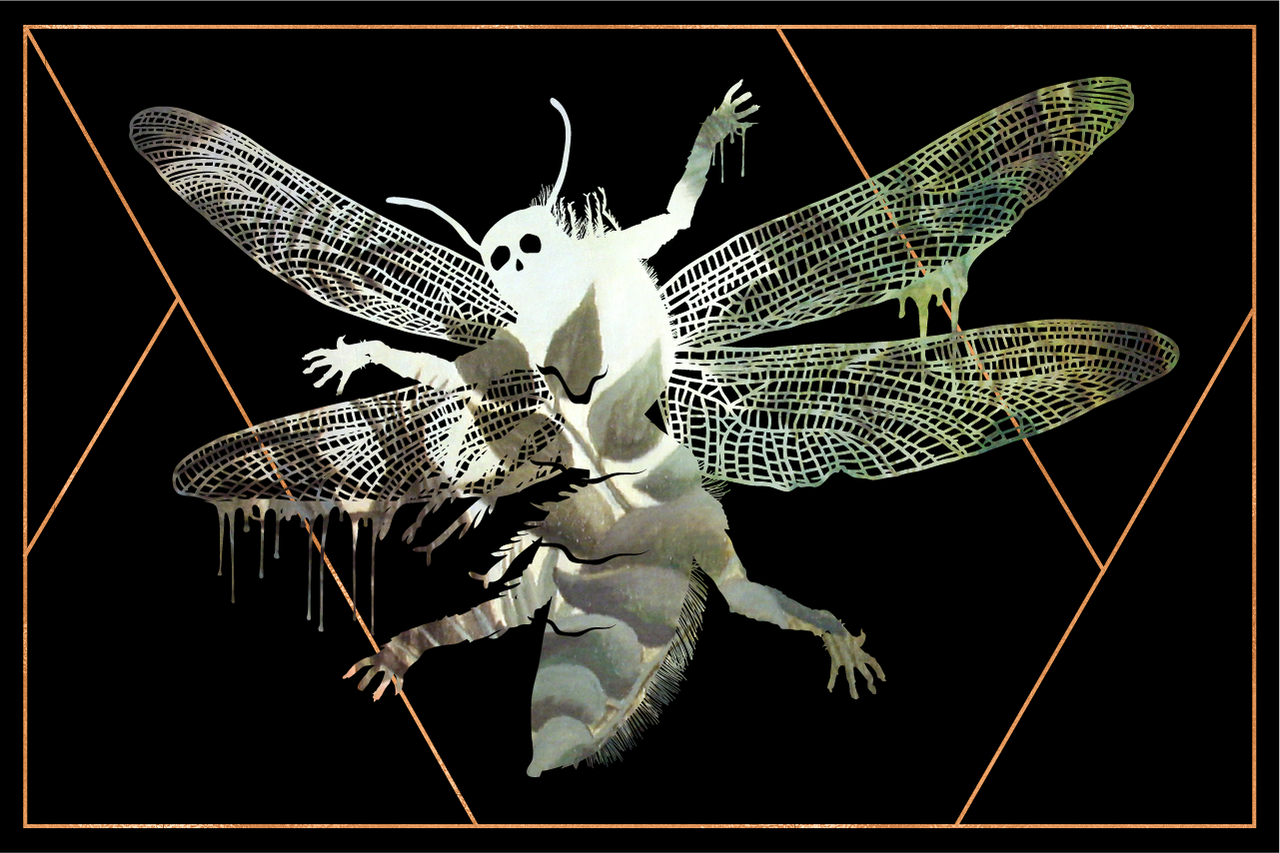

In West Africa, the Adze Is an Insectoid Source of Misfortune

Historians believe it originated with the fear of mosquito-borne illness.

Atlas Obscura and Epic Magazine have teamed up for Monster Mythology, an ongoing series about things that go bump in the night around the world—their origins, their evolution, their modern cultural relevance.

As night settles across Togo and Ghana, the adze, it is said, slips through keyholes, under windows, around doors. They fly to the bodies of the sleeping, appearing as mosquitos, beetles, fireflies, or simply balls of light. The adze prey on men and women, but enjoy the blood of children most of all.

For centuries, the Ewe people of West Africa have lived in fear of the adze. As legend goes, there’s no potion, spell, or weapon that can ward one off, and no cure for the bitten. The adze will either drain the person of life, or possess them, consigning them to madness or misery—if not both. When asked about the adze, one Ewe professor based in the United States replied, “I’ve come across adze, but only as a witch. Witches in this culture are real, not mythical.” (He did not respond to further requests for comment.)

There’s no record of when the lore of the adze first began. Archaeological evidence shows that the Ewe people settled the coast of West Africa, in the tropical region of what is now Ghana and Togo, around the 13th century. Historians believe the adze originated as an explanation of and warning against malaria and other insect-borne diseases that the Ewe people felt powerless against.

In the 19th century, after Christian missionaries from Europe established colonies in the region, the adze evolved into a scapegoat for a range of other evils—personal, cosmic, biological. If an individual showed signs of jealousy, mental illness, bad luck, addiction, marriage problems, or the inability to conceive a child—just to name a few—adze possession was often considered the culprit.

According to historian Brian P. Levack of the University of Texas at Austin, author of New Perspectives on Witchcraft, Magic, and Demonology: Witchcraft in the Modern World, as the Ewe people were exposed to the teachings of missionaries, they did not forgo their traditional religion of Vodun—which means “spirit” in Ewe and is the source of the various Vodou or Voodoo traditions in the Americas—for Christianity. Instead, they loosely combined the two. “The Ewe Christians kept their old faith and fears and put the Christian Good on top,” Levack writes. The adze, therefore, began to merge with and resemble something more akin to the Devil.

This incarnation continues today. One member of the Ewe tribe who agreed to give insight into the adze canceled just hours before his interview. “I’ve had a bad dream the night after I agreed to talk to you about the Adze,” he wrote in an email. “I’ve been trying to pray about it since I’m a Christian to get some directions from God. Unfortunately I will not be able to move ahead with it [the interview]. I hope you understand.”

Just as Western women throughout history have been viewed as more susceptible to evil (from Eve to the Salem Witch Trials to Hilary Clinton), in Ewe culture, the adze are said to possess women more frequently than men. A woman who appears envious of her husband’s other wives, a woman who is infertile, or a woman with an uneven temperament are all thought to be possessed by an adze. Anthropologist Meera Venkatachalam, who documented her decade of fieldwork among the Ewe people in Slavery, Memory and Religion in Southeastern Ghana, c. 1850–Present, says she encountered many women accused of being possessed by the adze. “The adze was a widespread spiritual problem,” she says, “adze attacks were steady and relentless.”

While there is little that can be done to fight the adze, there may be a few ways to free someone from its possession. Some believe that the only way to defeat an adze is to force it out of its host and into a quasi-human form, a hunchbacked creature with talons and jet-black skin, and then kill it. As legend goes, this method is very difficult, as the transformed adze is agile and extremely dangerous. The more common method—particularly post-Christian invasion—is considered more effective, quite a bit easier, and familiar to anyone who knows the Christian theology of possession: vigorous prayer. Venkatachalam describes witnessing frequent “deliverance sessions aimed at expelling adze and potential witches from congregations,” which took “the form of intensive prayer sessions and exorcisms.”

But no matter the adze’s form or reason for attack, no one is safe from the tug of jealousy, the weight of sadness, or the bite of a mosquito.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook