The Little-Known Passport That Protected 450,000 Refugees

Between 1922 and 1938, the “Nansen Passport” allowed stateless people to make a new life.

On January 27, President Donald Trump signed a sweeping executive order that, among other provisions, barred all refugees from entering the United States for 120 days (and banned Syrian refugees indefinitely). As the ban, currently stayed by order of a federal judge, makes its way up through the U.S. court system, refugees all over the world watch closely, their futures hanging in the balance.

The current refugee crisis is the largest the world has ever seen—but it’s far from unprecedented. Back in the 1920s, civil war in Russia and genocide in the Ottoman Empire left millions of families stateless, seeking asylum in countries already stretched thin by the ravages of war. Charged with preventing catastrophe, an idealistic explorer named Fridtjof Nansen changed hundreds of thousands of lives with a piece of paper: the Nansen Passport. Although it stopped short of granting citizenship, the Nansen Passport allowed its holders to cross borders to find work, and protected them from deportation. Some experts are calling for a similar solution today.

Born in Norway in 1861, Nansen was an unlikely diplomat. A zoologist by training, he made a name for himself as a polar explorer—in 1888, he led the first team to cross Greenland by foot, and four years later, he traversed the Arctic Ocean by purposefully freezing his ship into an ice floe. When he aged out of constant adventuring, Nansen brokered his considerable fame into a political career, initially representing Norway in disputes with Sweden, and later serving as the country’s ambassador to Britain.

At the end of World War I, Nansen threw himself into existing efforts to create an international peacemaking body—what would eventually become the Paris Peace Conference, and then the League of Nations. In 1920, the League put Nansen in charge of a particularly tricky post-war problem: figuring out what to do with those displaced by conflict.

As the new High Commissioner for the Repatriation of Prisoners-of-War, Nansen negotiated for the return of hundreds of thousands of POWs held in Germany and Siberia. While working to secure their release, Nansen’s eyes were opened to another horror of war. “Never in my life have I been brought into touch with so formidable an amount of suffering,” he told the League in November of 1920, urging his fellow members to “prevent for evermore” the type of conflict that originally led to it.

But those gears were already in motion, and another displacement crisis loomed. In December of 1921, it hit: Vladimir Lenin, whose Bolshevik army had shocked the world by winning the Russian Civil War, revoked citizenship from Russian expatriates who had fled the country during the conflict. This left some 800,000 people stateless, dispersed throughout Eastern Europe. “The legal status of these people was vague and the majority of them were without means of subsistence,” wrote Fosse and Fox. “It was considered unacceptable that in the 20th century there should be such a huge number of men, women and children living in Europe unprotected by any system recognized by international law.”

Once again, the League of Nations put Nansen on the case, appointing him High Commissioner for Russian Refugees. He quickly began breaking down the problem. Neighboring countries, especially those who were dealing with their own conflicts, balked at the prospect of taking in tens of thousands of poor, stateless people. But if the refugees were sent back to now-Soviet Russia, they could face political persecution, imprisonment, and even execution.

Nansen’s instincts initially leaned toward repatriation, figuring that states should be made to accept their own citizens. But when he began investigating the problem personally, his opinion shifted. After one small group of refugees was sent back to the U.S.S.R. from Bulgaria, many were shot by Soviet authorities.

This did not stop Bulgaria: fearing Communism, they began forcibly deporting people, beginning with a group of 250, which they shipped off over the Black Sea in a small boat. When the ship reached the U.S.S.R., it was not allowed to land, so the refugees turned towards Turkey, which also rebuffed them. Panicked, many began leaping into the sea. Everywhere he went, Nansen was met by stories like this—of frightened countries, who feared foreign influence and their own dwindling employment, and of even more frightened refugees, who just wanted someplace to live.

At first, Nansen brokered individual arrangements. He sent some groups to Czechoslovakia and the United States, ensured that refugee camps had clothing and provisions, and made universities in those countries that belonged to the League of Nations promise to educate Russian students. But the problem outstripped this pace of action. What refugees really needed was a way to make lives for themselves—to travel, so as to find opportunity, and to work, so as to establish themselves in their new homes. They needed some kind of identity document.

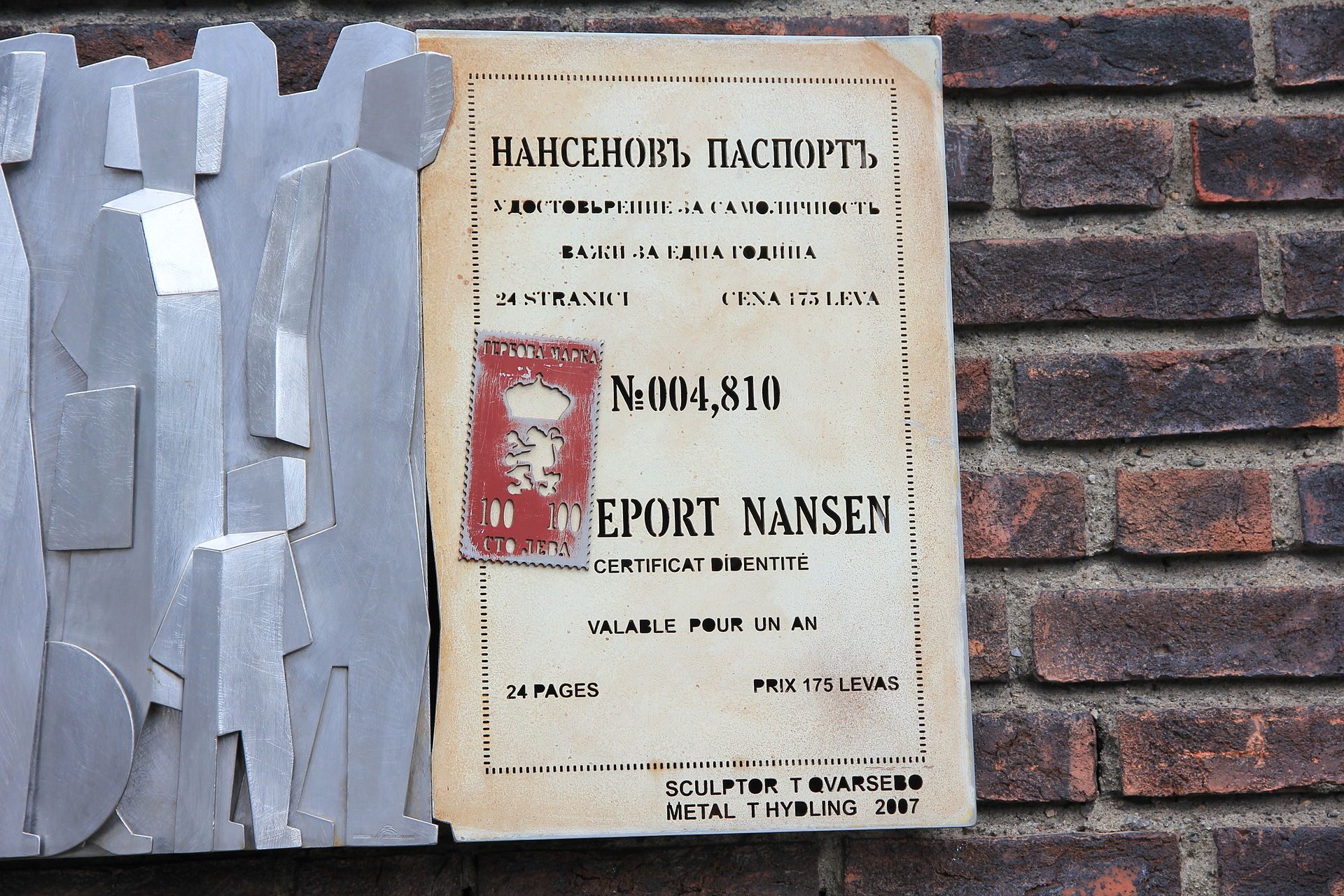

In March of 1922, at the Council of the League of Nations, Nansen proposed such a document: a “Nansen Passport,” which would allow refugees to travel and protect them from deportation. The passport was simple—it featured the holder’s identity, nationality, and race—but it served its purpose well. Its holder could move between countries to find work or family members, and they could not be deported. “This was the first time that stateless people had any sort of legal identity,” wrote Annemarie Sammartino in The Impossible Border: Germany and the East, 1914-1922.

This solution was by no means perfect. Unlike a regular passport, the Nansen Passport did not confer upon its holder the rights of citizenship—for example, it didn’t guarantee the right of return to the country that issued it. But as it slowly gained credence, it became more and more helpful to those who held it. By 1923, 39 governments recognized it. Two decades later, that number was up to 52, and the passports were issued to Armenian, Assyrian, and Turkish refugees as well. Sales of “Nansen stamps,” required annually to renew the passport, paid into refugee relief funds.

Nansen died in 1930, of an influenza-induced heart attack after going skiing against his doctor’s wishes. Immediately afterwards, the League of Nations set up the Nansen International Office for Refugees, which continued his work until 1938, when it was absorbed into a larger committee. That same year, the Office received the Nobel Peace Prize. By then, they had provided Nansen passports to about 450,000 stateless people, including writer Vladimir Nabokov, composer Igor Stravinksy, and ballerina Anna Pavlova. “There is no doubt that by and large, the Nansen certificate is the greatest thing that has happened for the individual refugee,” wrote journalist Dorothy Thompson, also in 1938. “It returned his lost identity.”

Today, global conflict, human rights abuses, and climate change have created tens of millions of refugees worldwide. Although Nansen’s legacy lives on in the form of the United Nations Refugee Agency, and in the Refugee Travel Documents currently issued in 145 countries, some experts think these provisions are not enough. “Only a rapid effort to revamp global refugee laws will permit a peaceful and managed transition from chaos — and the xenophobia and violence it can generate — to a semblance of world order,” wrote Michael Soussan, a former UN humanitarian worker, in Pacifc Standard in late 2015. “Refugees need and deserve real passports … The world body must live up to the challenge.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook