Nature’s Time Capsules: A Guide to the World’s Pitch Lakes

The notorious ooze of Rancho La Brea (photograph by Daniel Schwen/Wikimedia)

The notorious ooze of Rancho La Brea (photograph by Daniel Schwen/Wikimedia)

“Pitch lakes” represent surface deposits of oil bubbled up from subterranean reservoirs through faults or fissures, often formed when the layers of sedimentary rock that contain hydrocarbons are folded or squashed in tectonic upheaval. Evaporation removes the oil’s lighter elements to produce mucky ponds of asphalt, colloquially called pitch or tar, and technically referred to as bitumen.

Such seeps are widely scattered across the planet, both on land and in the oceans. One of the world’s biggest is Pitch Lake along Trinidad’s western coast, visited by Sir Walter Raleigh in 1595. A bizarre tract of semisolid asphalt strung with oily channels and pools, the lake — a popular tourist attraction — spans some 100 acres and plunges to 250 feet deep.

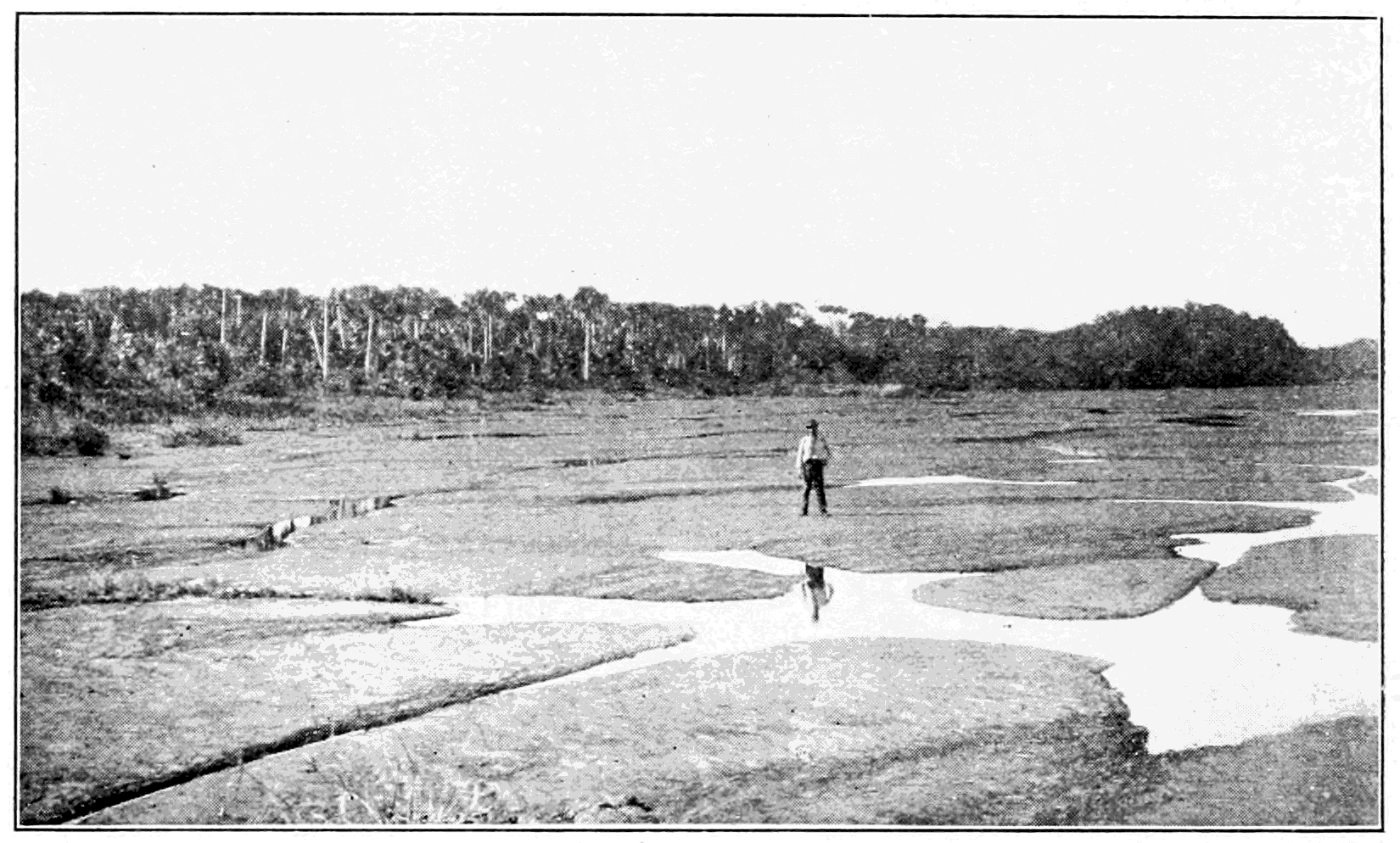

Trinidad’s Pitch Lake, one of the biggest asphalt lakes on Earth (photograph by Shriram Rajagopalan/Flickr)

Trinidad’s Pitch Lake, one of the biggest asphalt lakes on Earth (photograph by Shriram Rajagopalan/Flickr)

Trinidad’s Pitch Lake (photograph by Shriram Rajagopalan/Flickr)

Trinidad’s Pitch Lake (photograph by Shriram Rajagopalan/Flickr)

Multiple local legends explain the creation of this otherworldly landmark. One story suggests that deities opened the asphalt morass to swallow a Chaima village whose inhabitants, celebrating a victorious battle, recklessly feasted on sacred hummingbirds. (Incidentally, hummers are common sights around the lake today.)

A 19th-century photograph of Trinidad’s Pitch Lake, from a 1900 issue of Popular Science Monthly (via Wikimedia)

There are also numerous pitch deposits elsewhere in the Caribbean, as well as in northern South America, notably in Venezuela, where many are locally known as “menes.” Eurasia has important examples, including the Binagadi tar pit on Azerbaijan’s Absheron Peninsula, and the Great Okha Asphalt Lake on the Russian island of Sakhalin. The Dead Sea historically coughed up shreds of bitumen; its storied, salty waters were once called Lake Asphaltites. Southern California famously supports a number of prominent pitch lakes, including the Carpinteria, McKittrick, and Rancho La Brea tar pits, in addition to offshore tar seeps in the Santa Barbara Channel.

Given the substance’s wide-ranging utility as an adhesive, waterproofing agent, and pavement, humans have mined the asphalt from pitch lakes for thousands of years. The Chumash people of the California coast and offshore islands caulked their sturdy driftwood-carved sea canoes, or tomols, with tar from Rancho La Brea in the Los Angeles Basin and other regional seeps. Sir Walter Raleigh used Pitch Lake’s glop on his ship and professed it “most excellent good.” Since the early 1800s that deposit has been commercially tapped—including for pavement on roads far from Trinidad’s shores.

Death Traps

Beyond providing a readymade source of asphalt, pitch lakes are widely known as repositories of biological remains. Most celebrated is Rancho La Brea, given its astonishing and well-studied inventory of Pleistocene fossils. Since the early 1900s, scientists have retrieved better than a million vertebrate bones from these natural asphalt deposits, not to mention loads of invertebrate and plant remnants. (These are tar “pits” because of those excavations.)

Los Angeles’s own prehistoric boneyard has provided so much knowledge about ancient North America that paleontologists have named an entire Pleistocene span after it: the Rancholabrean North American Land Mammal Age. This period dawned with the arrival, some 200,000 years ago, of the bison — the most numerous big herbivore sepulchered at La Brea — in the New World.

Robert Bruce Horsfall’s 1913 depiction of Rancho La Brea in its Pleistocene heyday, showing a Smilodon square off against dire wolves over a bogged Columbian-mammoth carcass (via archive.org)

Robert Bruce Horsfall’s 1913 depiction of Rancho La Brea in its Pleistocene heyday, showing a Smilodon square off against dire wolves over a bogged Columbian-mammoth carcass (via archive.org)

Rancho La Brea showcases tens of thousands of years of deep history. The site’s environment is particularly propitious for fossil preservation; high winter streamflow out of the nearby Santa Monica Mountains annually washed in sediments that buried tar-bound carcasses.

The La Brea pits entombed a rich array of grazers and browsers. Besides the ancient bison — which appear to have been seasonal visitors to the tar pits, passing through the area in late spring — there are remains of western horses, camels, mastodons, tapirs, ground sloths, pronghorn, peccaries, and Columbian mammoths.

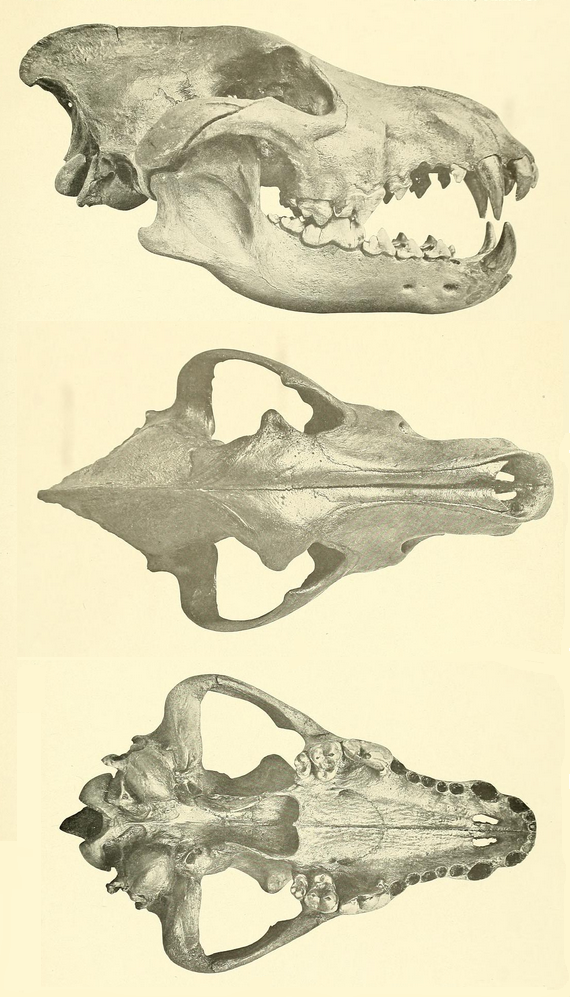

But carnivores significantly outnumber the plant-eaters, making up 90 percent of the catalogued large-mammal fossils. The dire wolf — a hulking canid more solidly built than its gray-wolf cousin — is better represented than any other large mammal: Fossils of more than 4,000 have been identified. More than 2,500 saber-toothed cats — Smilodon fatalis, specifically — are recorded from the site, and there’s been a healthy haul of coyotes. Other carnivores of Rancho La Brea include the American cheetah, the American lion, and the short-faced bear, a horse-sized (and all-around terrifying) ursid that may have actively run down ungulates or simply outmuscled wolves and big cats from their kills.

The formidable skull of a Rancho La Brea dire wolf, as displayed in John C. Merriam’s 1911 The Fauna of Rancho La Brea (Vol. 11) (via Wikimedia)

The formidable skull of a Rancho La Brea dire wolf, as displayed in John C. Merriam’s 1911 The Fauna of Rancho La Brea (Vol. 11) (via Wikimedia)

This plethora of killers suggests Rancho La Brea may have functioned as a “predator trap.” A mired bison, horse, or camel might have lured multiple predators and scavengers into the dangerous seeps. In addition to the mammalian carnivores, this raucous rogue’s gallery included a diverse roster of scavenging birds — from eagles, vultures, and condors to titanic “teratorns” with wingspans of 12 feet or better.

Entrapment of big mammals likely mainly occurred between late spring and early fall, when warm weather made the Rancho La Brea asphalt especially gummy. An ungulate — particularly a young or weakened one — may have become bogged down after entering the pitch pools to drink, or perhaps when chased by predators. Either way, the phenomenon was probably a relatively infrequent one. According to the on-site Page Museum at the La Brea Tar Pits, a once-in-a-decade “entrapment episode” involving 10 large mammals would be enough to account for all of the fossils identified so far.

Sculptures recreating ancient animal deaths in the La Brea Tar Pits (photograph by Kevin Stanchfield/Flickr)

Sculptures recreating ancient animal deaths in the La Brea Tar Pits (photograph by Kevin Stanchfield/Flickr)

A skeleton of Bison antiquus, the most common large herbivore represented in the Rancho La Brea fossil beds (photograph by Ed Bierman/Wikimedia)

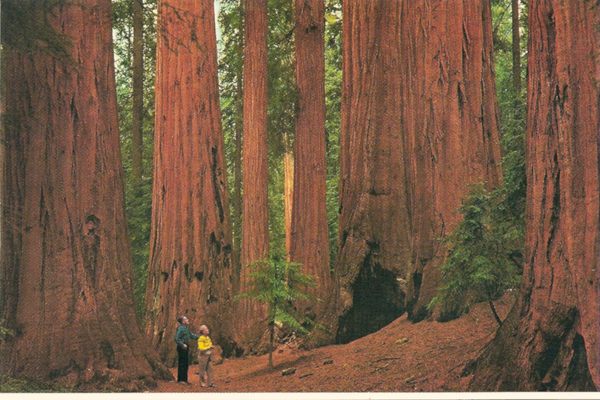

Less dramatic than mastodon bones or sabertooth fangs, the plant remains uncovered here nonetheless provide powerful insights into the Pleistocene ecology of the Los Angeles Basin. As the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County notes, vegetation communities native to the basin during the ice ages, from coastal sage scrub to canyon redwood groves, suggest a wetter, moister maritime climate similar to today’s Monterey Peninsula far to the north.

Rancho La Brea may be the best-known pitch lake for fossils, but others also boast prehistoric treasures, some perhaps comparable to southern California’s boneyards. Venezuala’s menes, many of which haven’t been formally inventoried, appear to be fossil-rich. The site called El Breal de Orocual, in which systematic excavations only began in the mid-2000s, has yielded several dozen species so far, from llamas to caimans. Pitch Lake has turned up a few odd fossils, too, including the tooth of a mastodon. Azerbaijan’s long-studied Binagadi asphalt lake reveals, through the petrified remains of cave hyenas and other beasts, some 200,000 years of Caucasus paleoecology.

From Tar Pits to Methane Lakes: A Galactic Detour

Earth’s asphalt lakes aren’t just registries of the planet’s prehistoric flora and fauna, they may also offer clues about the potential existence of extraterrestrial life. Scientists researching Pitch Lake in Trinidad have discovered that multitudes of microbes inhabit its seemingly inhospitable glop, apparently metabolizing the oil amid hot, water-deficient conditions. This particularly intrigues astrobiologists, because Pitch Lake offers something of a parallel to evocative environments over 700 million miles away.

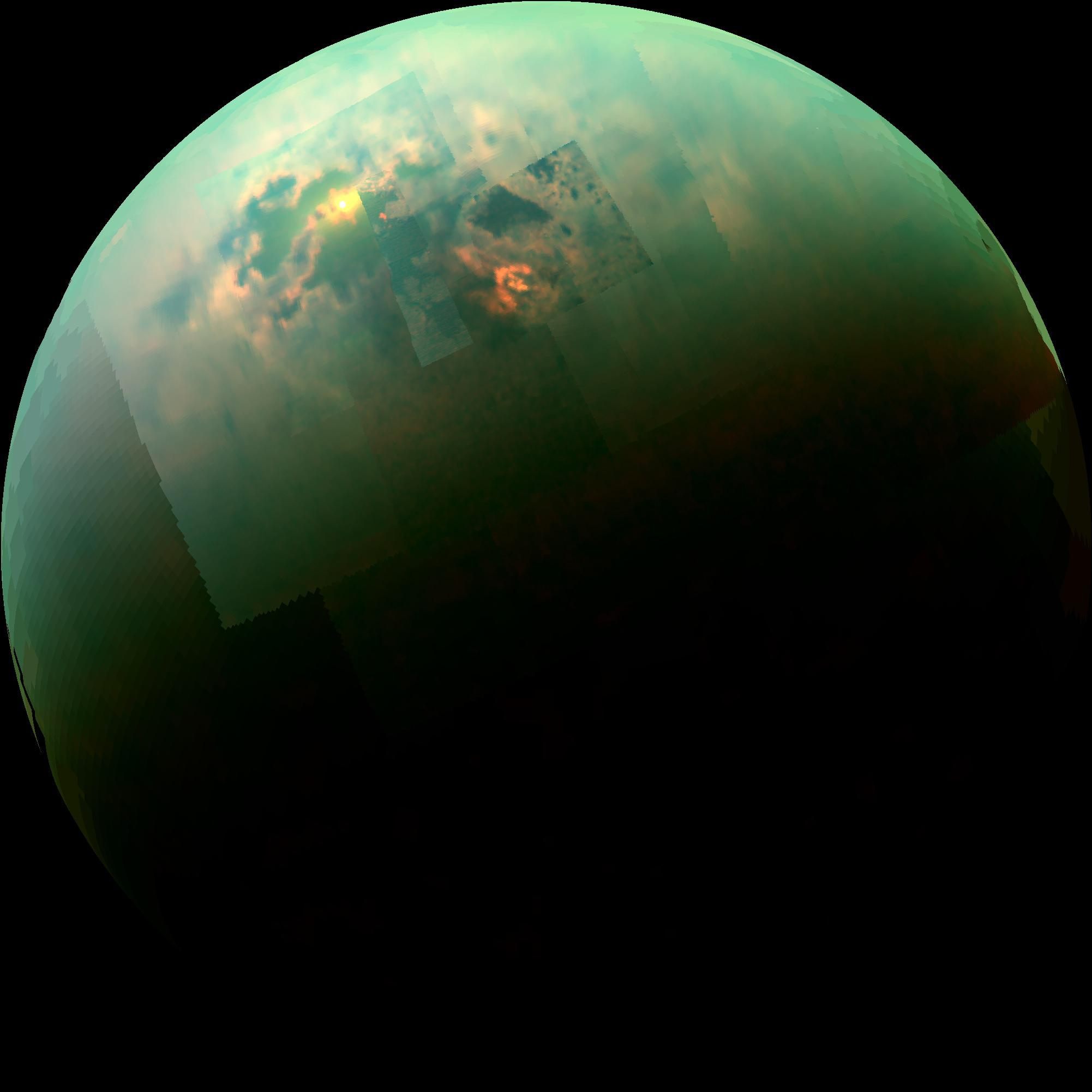

Huge seaways and lakes of liquid methane, ethane, and other hydrocarbons have been identified on Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. Its biggest, Kraken Mare (named for the legendary sea beast), spans some 154,440 square miles. These features, best documented around the moon’s polar regions and the only surface liquid known in the solar system outside Earth, may harbor “about 2,000 cubic miles (9,000 cubic kilometers) of liquid hydrocarbon, about 40 times more than in all the proven oil reservoirs on Earth,” according to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Reflected sunlight shimmers on Kraken Mare, the largest of the hydrocarbon seas of Titan (via NASA)

Reflected sunlight shimmers on Kraken Mare, the largest of the hydrocarbon seas of Titan (via NASA)

Titan’s physical geography shows parallels with Earth. Its hydrocarbon lakes, rivers, clouds, and rain may integrate in a “methanological cycle” similar to our planet’s water cycle, and there’s some evidence for both volcanic and tectonic activity on the moon. These Earth-like conditions make Titan one of the solar system’s more promising zip codes for the existence of life. If microbial organisms can prosper in our planet’s own hydrocarbon mires, perhaps Titan’s remote, alien seas conceal extraterrestrial counterparts.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook