It’s Official: There’s Another ‘World’s Largest Snake’

Even actor Will Smith saw it slither through the Amazon.

The cloudy swamps and creeping streams that cover vast expanses of South America harbor some of the most hair-raising wildlife on the planet: poisonous frogs, electric eels, deadly mosquitos, and grinning caymans are just some. The Amazon is no place for someone who is spooked by things slimy, scaly, or hidden under murky water with only menacing eyes and nostrils visible. And yet that’s exactly what Jesús Rivas has looked for when he’s waded through the wetlands of South America over the past 32 years.

Rivas, a biology professor at New Mexico Highlands University, is an anaconda expert. In his decades of research, he has collected hundreds of blood and tissue samples to expand our collective understanding of the world’s largest snake, ultimately to protect it against threats like human impact and climate change. With a team of fellow researchers composed of both academics and Amazonian Indigenous peoples, he has discovered a major divergence in the green anaconda, one of historically four anaconda species.

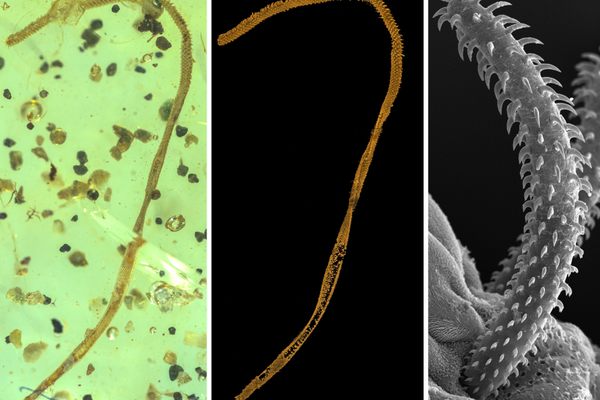

Green anacondas are the heaviest snakes on the planet and the second longest, after reticulated pythons. They occur in the wet tropics of South America, east of the Andes, from northern Venezuela to the south of Brazil. Until recently, the green anaconda was thought to be just one species, Eunectes murinus, but a newly released study headed by Rivas found out there are actually two. The research describes major genetic differences between green anacondas in the northern half versus the southern half of their range.

“We got the first hints that [the northern] species was different from the southern one in 2007,” Rivas says. “Then we started the hard process of gathering samples from all over South America.” Even though the two snakes appear identical, DNA sampling shows a drastic genetic difference of about 5.5 percent. That’s a bigger difference than the one between humans and chimpanzees. When two or more species are classified as one because they are morphologically indistinguishable, they’re called “cryptic species.” This is the case for the green anaconda, whose northern and southern populations are virtually identical in their massive size (reaching lengths of 30 feet and weighing up to 550 pounds) and coloring (olive green with dark splotches along their backs and sides).

Bryan Fry, co-author of the study and professor at the University of Queensland in Australia, says the key difference between the two populations is the geographic range. Years of field work and sampling revealed that specimens studied across the northern part of the green anaconda’s distribution were actually of a sister clade of E. murinus, which the researchers have named E. akayima. Whereas E. murinus (the southern green anaconda) can be found in Venezuela, Trinidad, Guyana, Suriname, and presumably Colombia, the second species E. akayima (the northern green anaconda) inhabits Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil. The species stick to their separate zones except for in French Guiana, and the study suggests that country “might be a contact zone for these two groups.”

In 2022, Rivas, Fry, a local Indigenous leader, actor Will Smith, and the crew of National Geographic’s “Pole to Pole” series embarked into the Waorani Territory of Ecuador and found evidence that the northern green anaconda is present there as well. That Indigenous leader, Penti Baihua, and his son, Marcelo Tepeña Baihua, are listed as co-authors on the study, and Will Smith is mentioned in the acknowledgements.

“One key factor that allowed us to make the publication now is new developments in our understanding of the history of South America,” Rivas says. He clarifies that the two species weren’t always so different. They likely diverged millions of years ago as a result of a ridge that rose and geographically separated the north and south. Now that there’s data to support that the green anaconda is made up of two claves, researchers can begin to work out the unique needs of each so these enormous snakes can continue slithering about and dominating the jungle.

“The discovery of a new species is always important,” Rivas says, “as it informs us better of the diversity we have—and may lose.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook