The Ghost Villages of Newfoundland

A controversial government resettlement program has left centuries-old fishing villages abandoned.

The small village near Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, was once a charming place to live. A quaint, centuries-old fishing village, that overlooked the sea, with winding lanes, asymmetrical “saltbox” family homes, and quiet streets filled with a post office, church, and a graveyard. It would be an idyllic, country scene, apart from the fact there are no people.

The Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador is home to around 300 such ghost villages.

Between 1954 and 1975, around 30,000 people were relocated as part of controversial government “resettlement” programs. Today these abandoned villages are largely forgotten and unknown, except by those who once lived there.

Newfoundland and Labrador is a vast, beautiful, often remote and isolated place. The wild landscape is home to unusually named towns such as Come By Chance, Heart’s Desire, Happy Adventure and Chimney Tickle. Dotted sparingly along its miles of rugged shorelines, and in the shelter of its thousands of tiny islands, are the “outports”; small, tightly knit fishing villages, many dating as far back as the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

By the end of World War II, the population of Newfoundland stood at around 320,000, spread out over a thousand such settlements, three quarters of which held under 300 inhabitants. Some villages, such as Tacks Beach on King Island, had a population of several hundred, while others such as Pinchard’s Island, Bonavista Bay, had just eight families living there.

These communities were largely self-sufficient, and mostly isolated from each other. They lived by fishing the abundant cod and herring fields, and by logging and seal hunting.

But life in the outports was to change forever in 1949. That was the year Newfoundland and Labrador, Great Britain’s first permanent colony, voted to join Canada. Following confederation, the government began to take a keen interest in these hundreds of isolated communities. Pondering what to do with their vast new territory, with its rich fishing fields, it commissioned studies undertaken by the Department of Welfare and the Department of Fisheries.

Anthropologists dispatched from Memorial University in St. John’s—the capital of Newfoundland—found that in Placentia Bay, located in the southwest, only 68 percent of children could read and write. Medical care was sparse. Some small communities, such as Come By Chance, had a cottage hospital, but they were few and far between. Some of the more remote outports were served by occasional medical ships such as the M.V. Lady Anderson, which ferried doctors around on 40-foot boats. One fisherman interviewed on King Island explained that “if the wife got sick … it’s two hours away [by sail] and if it was rough, you mightn’t get there at all.”

Experts landing at Little Brehat, a bay in northern Newfoundland found a fishing village of 14 families, with “no road connection, no agricultural potential” that was “often completely isolated in winter.”

The Canadian government concluded that a significant part of the Newfoundland population was living in conditions not far off the 19th century. But many people living in the islands were reluctant to leave the only home they’d ever known. The Government Game, a protest song about resettlement written by poet Al Pittman in 1983, includes this verse:

My home was St Kyran’s, a heavenly place,

It thrived on the fishin’ of a good hearty race;

But now it will never again be the same,

Since they made it a pawn in the government game.

And the costs to modernize the new province, to provide electricity, telephones, medical care, and education at a level that would match the rest of Canada, would be enormous given the distances involved. Over on Sop’s Island, population 222 in 1956, the government inspectors recorded that because “there are no roads and because of the rugged and mountainous country, the cost of building roads … would be tremendous.”

For the Department Of Fisheries, the primary concern was how best to capitalize on the rich fishing industry of its new province. Small fishing villages were to make way for deep-water ports capable of berthing deep sea trawlers, bringing their catches back to modern, mass processing plants. “Formally one case of the resettlement may be based on the economic non-viability of the Newfoundland fishing ports,” concluded a report by the Canadian Council on Rural Development, which was ominously titled “Economically Worthless.”

The only solution, it seemed, was to make the distances between these increasingly isolated villages smaller; their inhabitants would have to move to larger “Growth Centres.” Asked one government official: “Could the settlers upon these barren little islands and the rugged creeks and coves which present no basis for growth and prosperity, be induced to remove en masse?”

Michael Skolnik at the Institute of Social Economic Research at Memorial University, St. John’s, put it more bluntly: to end “peasant subsistence … is to facilitate the process of urbanization.”

The government report on Sop’s Island concluded: “In my opinion, the settlement should be completely evacuated.”

The first inklings of the change came in 1957, when a government questionnaire was sent to “doctors, clergy and other responsible persons” living in these peaceable villages. The questionnaire was to gather their “opinions as to those settlements suffering from social and economic problems and which might be vacated.” And so the doctors and vicars began surreptitiously weighing up the future of the outports and whether centuries of tradition were to be suddenly abandoned.

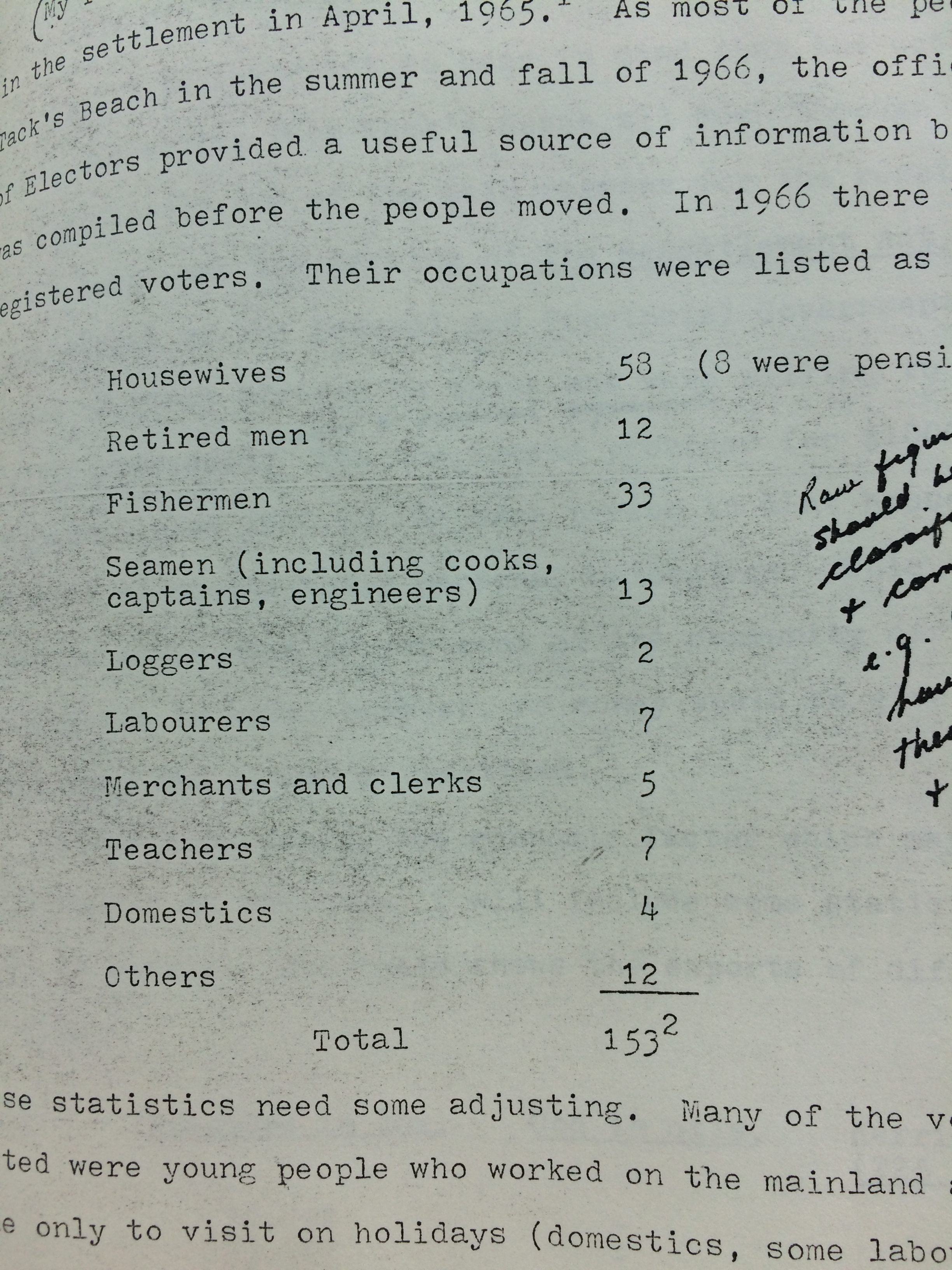

One such village was Tacks Beach, a small community on King Island, whose natural inlet provided a perfect harbor for the fishermen who lived there. By 1961, Tacks Beach had a population of 153 registered voters, one of whom, Howard C. Brown, would write a case study of the abandonment of his childhood home in St. John’s, a decade later. He described a picturesque island community that “had a large Anglican church, a four-room school, an Orange Hall (a fraternal organization), a Post Office, and a large general store” run by his family. Tacks Beach was connected to the outside world with a telegraph office, and a weekly supply boat, chartered by the government.

But Tacks Beach would not survive the government inspectors, who were alarmed at the education levels in the village, noting that “in late August of 1966 no one knew if there would be a teacher … for the coming school year.” The boom was soon to be lowered.

At first the proposed resettlements were to be decided on by the outports themselves. A petition and vote was held, with a majority of 80 percent needed for the village to be abandoned. These petitions saw the villagers at each other’s throats. Often the divisions fell according to age, with the younger families keen to move because of education. “It is so much better for the children,” wrote one Tacks Beacher. “The younger ones will get better education than the two eldest.” Others, often with their loved ones buried in local cemeteries, were desperate not to give up their trusted way of life, their family homes and their heritage.

To sweeten the resettlements, financial incentives were offered by the government. The sums started at $400 per family in the 1950s (at a time when the annual average salary for a fisherman was around $500) and rose to $1,000 per household by the next phase, with an extra $200 for each dependent.

But where some outports held out, clinging to their old way of life, unofficial coercion saw the vital post offices threatened with closure. One by one, the old outports were steadily vacated.

The resettlement saw the surreal sight of many cottages being moved in one piece, so-called “sturdy homes,” dragged by the villagers over ice, or floated across the water to their new homes, buoyed by oil drums. The homes that couldn’t be moved in one piece were simply left.

On Flat Island, 500 people crammed into St. Nicholas’ Church for one final service before being split up and relocated to the urban growth centers.

Over on Tacks Beach, most people moved at Christmas, 1966. One villager recorded a poignant handwritten account of the last days of the island, which is now held in the archives of The Rooms Museum, St. John’s, they noted down that one Garfield Brown had the first house to be taken away, and that the last person to leave the island was Arthur Comby, aged nine. They recorded that the last couple to be married were George Brow and Bertha Perry, on December 29, 1965. Seven families stayed at Tacks Beach for a final Christmas holiday in their homes, but by the autumn of 1967, the entire island was abandoned.

Scott Osmond, who runs the Hidden Newfoundland website, and who has explored many of the abandoned outports, says “the Newfoundland resettlement program of the 1950s and ‘60s continues to be a unique look into the provinces past. These isolated communities reflect a time when the people of Newfoundland relied entirely on the sea, forcing them to live in every little cove and inlet along its rocky shores.”

Since the resettlement, the hundreds of villages are slowly being reclaimed by nature. Some have gradually crumbled away, while others remain frozen in time, as though the people who lived in them had suddenly disappeared.

“While many have been washed away to nothing but grassy fields and barren landscapes, they still pose as a memory to the harsh economic times faced by Newfoundlanders throughout their entire history,” says Osmond.

The resettlement remains a controversial topic in Newfoundland, and its after-effects are still felt today. It is difficult to evaluate the benefit of reduced isolation, better education and medical care against the loss of traditional homes, culture and way of life that centered around the old fishing grounds.

Photographer Scott Walden has visited many of the abandoned resettled communities to capture their remnants.

“I came across many who’d been resettled, some as children, some in their middle age,” he says. “There was an ambivalence, as everyone was aware that education and healthcare was better in the ‘growth centers’ to which they were relocated, but at the same time, they were aware of how beautiful the coastal communities had been. Contrast that beauty with the dreary service towns that the growth centers have developed into, all full of subdivisions and arterials, complete with the usual array of fast-food joints and gas stations.”

His photographs capture the gradual disappearance of these once-vibrant communities. Houses are left empty, small graveyards untended. “If there was a settled opinion at that time, it was that the government should simply have left the coast communities to slowly decrease in population as young people left to go to college in the larger cities, and then stayed in those larger cities to raise families of their own,” says Walden. “This would have been much easier on the older people, the ones who had established lives and social positions which were destroyed by the relocation. I think it was hardest on those people.”

One resettled fisherman reflected that “within a generation the province has changed immensely and people of today rarely have the same sense of community or interdependence that most of us were privileged to experience, perhaps we took it all for granted.” The St John’s Evening Telegram ran a story on Oct 1, 1971, with an altogether more harsh view: “First-class, viable communities were being wiped off the map with a few trips of the government barge.”

Rex Brown, a fisherman on Tacks Beach was one of the 30,000 resettled, his old way of life gone forever. Speaking of living in the one of the new urban growth centers, he said, “undoubtedly the sunset was beautiful. If only you could sail or row into one.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook