One Man’s Fight To Save a Mental Hospital’s Forgotten Cemetery

John Horne is determined to preserve the stories of those who were left behind.

On a brilliantly sunny fall day in Washington state’s Skagit Valley, the grass at the Northern State Hospital Cemetery is shining with dew. To the uninitiated—those who zoom past on Highway 20 or stop to stroll through the abandoned hospital’s farm buildings in the Northern State Recreation Area—the cemetery appears to be nothing but a flat field of grass. But to volunteer John Horne, the glistening field is riddled with clues. He can tell by the way the grass is growing or dying whether there are graves nearby, and he has learned to interpret the jumble of letters and numbers on the field’s stone markers to reveal the identities of those buried below.

Horne is a kind of cemetery detective, committed to understanding what happened at the burial ground for what was once the state’s largest mental institution. Fifty years after Northern State closed, he works against time and the elements, not to mention bureaucratic neglect, to piece together the stories of the place and to work toward a memorial that would bring dignity to the roughly 1,800 souls buried there. Amid renewed interest in the hospital, he hopes to bring some measure of justice to those buried in its cemetery, who were often forgotten in both life and death.

Northern State, which closed its doors in 1973, doesn’t fit tidily into our ideas of how mental hospitals should look and work. Instead of grim towers and high fences, the hospital buildings feature a glamorous Spanish Colonial Revival design, with cream stucco and terra-cotta tiled roofs that stand out against the dreamy blue and white of the Cascade mountains. Famed landscape architect John Charles Olmsted designed the stately campus just a couple of miles east of Sedro-Woolley, a former mining and logging hub in the far northwest of the state. Olmsted believed beauty could be healing, and Northern State was meant as a refuge, a place where fresh air and honest work might repair shattered minds.

The institution opened in 1909 as a farm that served the Western Washington Hospital for the Insane in Steilacoom, but soon became its own facility, first called the Northern Hospital for the Insane. At its peak in the 1950s, around 2,700 patients lived on the grounds. They labored in the dairy farm and canning operation, producing vast amounts of canned meat and applesauce. While some were confined to wards, many had free reign of the 1,100-acre grounds, and even built shacks by the river to relax.

At Easter, according to local writer Mary J. McGoffin’s book Under the Red Roof: 100 Years at Northern State Hospital, patients organized an egg hunt for Sedro-Woolley kids, while at Christmas, townsfolk brought patients presents. It’s also worth noting that only some of the people at Northern State would today be classified as mentally ill. Many were not: They were epileptic, immigrants, menopausal, socially nonconformist, or merely old and unable to care for themselves.

“Northern State has a complicated history, like most large institutions,” says A. Muia, a Northern State Hospital researcher. “There was wonderful care, alongside stories of neglect and abuse. People got better and sent letters of gratitude, while newspapers picked up on scandals.”

Some of those scandals involved the treatment of remains. While the majority of those who died at the institution were claimed by their families, about a quarter were not, according to Horne, the cemetery’s most staunch protector. Many of the unclaimed were cremated and stored in metal food cans, sometimes for decades before finally being buried. Others, whose religion forbade cremation, were buried in coffins in the cemetery. Some unclaimed cadavers were provided to the University of Washington School of Medicine for dissection. In 1981, a vanload of body parts in bottles and jars was reportedly dumped at a landfill in Acme, about 15 miles away from Northern State. In 1983, around 200 cans of unburied ashes from Northern State were discovered on the shelves of a funeral parlor; they were later buried at Hawthorne Cemetery in Mount Vernon, Washington.

In the years since the hospital’s 1973 closure, the cemetery has often been treated as something of an afterthought: a situation Horne is hoping to change. A former social worker, he knows the campus well, having worked from 2007 until 2020 in a drug treatment center located at the former hospital. He’s been volunteering at the cemetery for about three years, moved to do so by other locals who complained about the neglect of the place—headstones stolen or vandalized, floods, a history of the land being unfenced and leased out as cow pasture.

“I’d heard people, since I moved here in 2007, complaining about the cemetery and how it’s not taken care of, this needs to be done, that needs to be done. Well, do it. So I do it,” he says standing at the back of the burial ground under cold shadows cast by the towering Arborvitae trees.

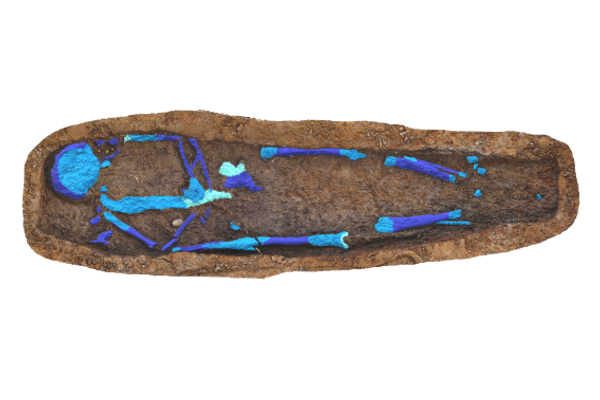

When Horne began working at the cemetery, only about two dozen of the flat stone markers—carved only with patient initials, not full names, due to privacy laws—could be seen. Now, he’s uncovered around 200 headstones and identified about 400 more graves, sliding metal probes down into the soil to find them and marking the locations with Roundup, killing a small area of weeds and grass, and orange ground-marking paint. He works to keep the headstones already above ground visible by trimming carefully around their edges, tapering the surrounding turf down until the stones are laid bare.

“I think that when a little chunk of concrete with a number and initial on it is the only thing left of someone’s life you should at least be able to see it,” he says.

But each winter, nature undoes some of his work—rains make the soil soggy, which sucks the markers down so they have to be excavated all over again. Last winter, he says, he lost three or four rows of graves, about 150 markers in total.

Fortunately, Horne likes the work, laboring by himself late into the night sometimes. He dismisses any idea that the cemetery might be spooky after dark, calling the place peaceful. Besides, cemeteries have always appealed to him, he says. “I love the human element of things here, and the mystery of things.”

The Northern State cemetery is a place of many mysteries, only some of which Horne has been able to solve. Perhaps the greatest mystery? Whether the whole thing was moved.

“There’s a whole lot of evidence pointing to the fact that [the cemetery] is not where it’s supposed to be,” Horne explains. He gestures to a wooded area north of where we stand at the back of the cemetery; it’s now choked with blackberries and furrowed by a deep ravine, but Horne thinks that most of the cemetery was once located there. Early descriptions of the property and the original sale deed describe a 10-acre site with a different shape than the current site. He suspects that after the hospital built the crematory in 1927, they realized they no longer needed the whole 10 acres. But Horne thinks that while they moved the headstones to the current location, they likely left the bodies in the wooded area now behind the fence.

Since a July 2023 feature by the Seattle Times on Northern State, there’s been increased interest in finding the forgotten graves at the cemetery. Several local politicians say they want to raise funds for ground-penetrating radar to survey the site. A woman who runs a business using cadaver dogs, which can sniff out remains even after many years, has also reached out to Horne. But either initiative would take money. Horne is just one person, not a non-profit; he can only do so much.

For now, he works to keep the dead alive in other ways. He’s created a gigantic spreadsheet with the names of everyone he can find interred at the cemetery, using old burial records and death certificates and matching them to the initials on grave markers. So far, he has 1,600 names on the list but suspects there are at least 200 more to add. He’s even found the death certificate for the first patient buried there, in 1911, and one of the last burials, that of a patient’s leg in 1952—shortly before a law ended burials at state institutions, instead turning the deceased over to local funeral homes. After this change, the cemetery was no longer used. Horne isn’t sure where unclaimed patients who died between 1953 and the hospital’s closure were ultimately buried.

Horne also manages a Facebook page for the cemetery and a Facebook group, Friends of Northern State Hospital, where he posts information and fields requests from descendants of those who died at the hospital. Over the past couple of years, there’s been an explosion of interest from people looking to fill in the gaps on their family tree. “I like connecting things, bringing people back to life,” Horne says.

Ultimately, though, what he would like to see is a memorial at the site that includes all of the names of those buried there—with room for more, “because you’ll always find more,” he notes. There is a small memorial at the cemetery currently, erected in 2004 after a Sedro-Woolley High School history teacher inspired three senior students to raise money for a plaque, but the numbers on it are not correct, Horne says. For now, a more comprehensive memorial is little more than a pipe dream.

Restoring the cemetery could mirror the transformation of the campus itself, which is in the process of being repurposed into a mixed-use business center known as SWIFT (Sedro-Woolley Innovation for Tomorrow; the name is also a nod to the migrating birds who visit the campus each fall). The farm buildings, in picturesque decay, have been repurposed into a public recreation area popular with tourists and locals alike. The cemetery, meanwhile, which is owned by the city and not managed by SWIFT, is far less valuable economically, and far more easily ignored.

Around the country, other cemeteries connected to mental institutions are also undergoing transformations meant to bring more dignity to the dead. Portland, for example, is working on a memorial for 185 patients of the Oregon Hospital for the Insane who were buried in the historic Lone Fir Cemetery. In Athens, Ohio, the National Alliance on Mental Illness is involved in an effort to “restore, beautify and demystify” three graveyards on the grounds of what was once the Athens Lunatic Asylum. In Steilacoom, Washington, at Western State Hospital—of which Northern State was once an offshoot—a group of volunteers called the Grave Concerns Association have installed a memorial and replaced 2,000 makers at a patient cemetery, bringing in school groups and service clubs to help with the cleanup and participate in conversations around mental health.

Alongside all of this is a shift. “I think attitudes have changed toward mental illness in the last few years,” says Muia, who works for the Sedro-Woolley Museum on special projects related to Northern State and wrote a self-guided tour booklet about the hospital grounds. “People are much more open about their struggles. There’s more support and less shame. In the early years, some families told others that their relative had died, rather than admit that he or she was in a mental hospital. Things weren’t talked about as much. Now, when the public hears of patients who were forgotten [they are] much more sympathetic. There’s support for remembering these individuals and honoring them.”

For Horne, restoring the cemetery and remembering those who were laid to rest here “gives some respect and dignity to the people who were thrown away.” He says, “I’m a big believer in going back and doing what you can to” fix past wrongs. “You can’t take it back, but you can do something to try to correct it.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook