Object of Intrigue: Confederate Currency

In 1861, imagery on American banknotes included railroads, Greek goddesses, and slavery.

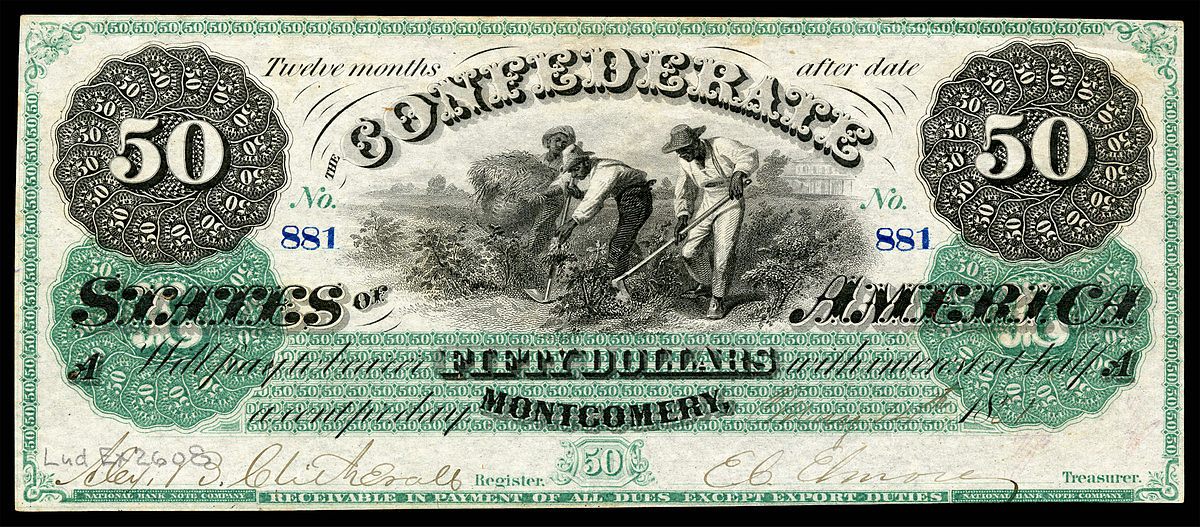

A Confederate $50 bill, issued in 1861. (Image: National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History/Public Domain)

American banknotes today feature mighty presidents of yore, grand buildings of the nation’s capital, and eagles. In 1861, the banknote imagery of choice included brand-new railroads, Greek goddesses, and slavery.

When Deep South states seceded to form the Confederacy in early 1861, they started issuing their own currency. The first series of Confederate States dollars was introduced in April 1861, on the eve of the Civil War.

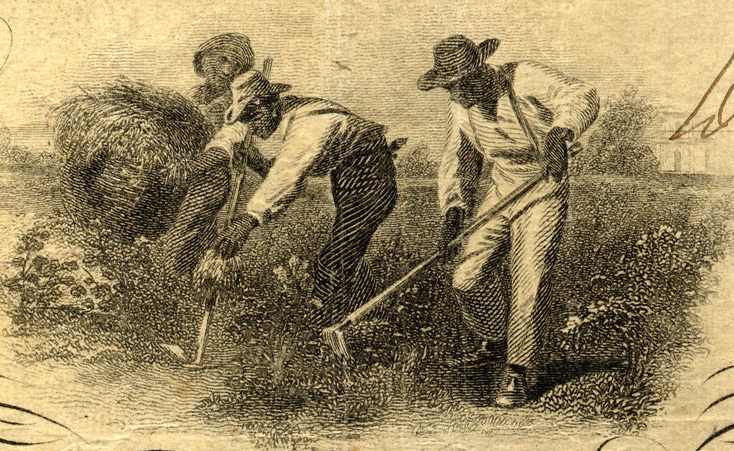

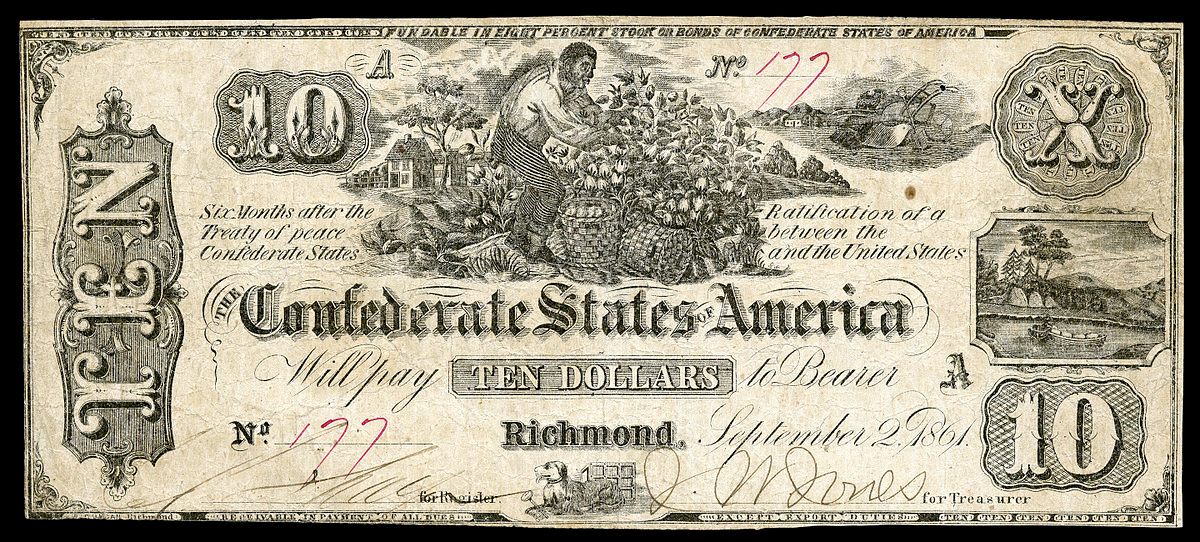

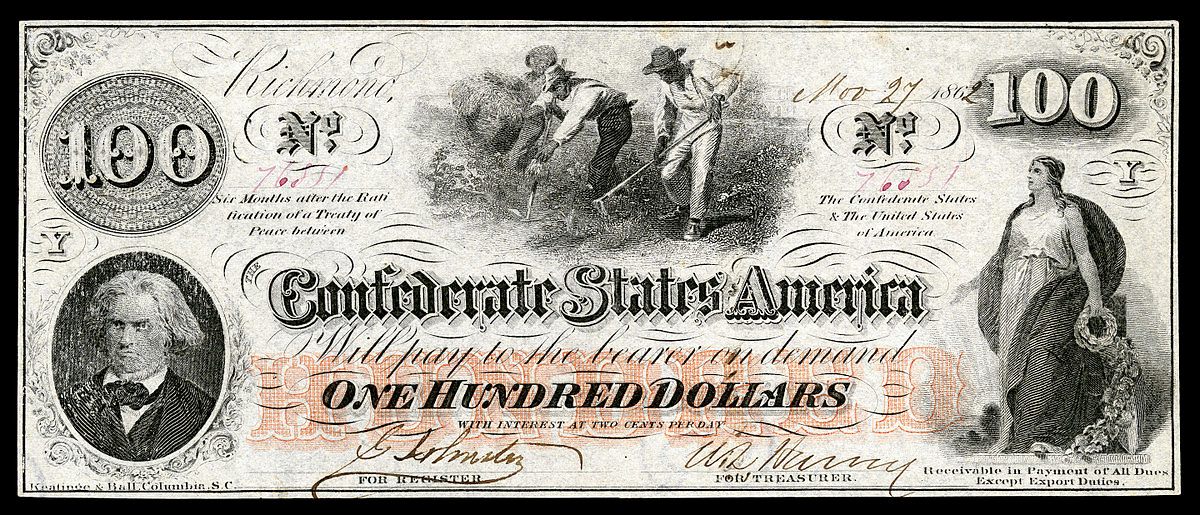

Each bill was stamped with a mishmash of imagery intended to inspire, but none more strikingly so than the $50 and later $100 notes, which depicted, among other vignettes, a trio of slaves working in a cotton field.

Detail from a Confederate $100 banknote. (Image: Public Domain)

Romanticized depictions of slavery on banknotes were not a new concept at the time. Individual banks in southern states had been putting images of slaves working the fields on their bills since the 1850s. (The 19th century was the height of the Free Banking Era, a time of unregulated, decentralized economics in which individual banks could issue their own currency.)

With the dawn of the Civil War, however, Confederate bank notes became scraps of Southern hope in the fight to retain slavery. The initial 1861 series was followed by six more sets of notes, with the final series issued in 1864. Each bill was a pocket-sized piece of Confederate propaganda that could be spread far and wide—within the southern states, and up into the Union.

In putting images of slaves hoeing cotton fields, loading carts, or carrying bags of corn on its currency, the Confederacy affirmed its unashamed reliance on slavery as a fundamental part of the Southern economy. Furthermore, as Louisiana State University journalism professor Jules d’Hemecourt put it, stamping the cash with such imagery alongside mythological Greek gods and goddesses made a dogged statement that slavery “would continue to exist in perpetuity, protected by law and sanctioned by tradition, and all but divinely ordained in iconography.”

A Confederate $10 note issued in 1862 depicts a slave picking cotton. (Image: National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History/Public Domain)

The images were certainly imaginative. Slaves were shown with placid or even jolly expressions on their faces, working in pleasantly agrarian conditions with nary a punitive plantation owner in sight. Due to Confederacy’s limited engraving resources—the nation’s best money printers were in the north—some pre-existing engravings were repurposed and tweaked.

For example, an image of a white farmer carrying a sack of corn that originally appeared on a bill issued by the Citizens Bank of Washington, D.C., was transformed into a corn-carrying black slave and put on a note issued by the Bank of Howardsville in Virginia.

A Confederate $100 note issued in 1862, featuring slaves working a cotton field (center) and Columbia (right). (Image: National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History/Public Domain)

As the war dragged on, Confederate State dollars depreciated. The notes weren’t backed by gold or silver and had no guaranteed value—they were a placeholder that promised the bearer payment in the event that the South triumphed over the Union and declared full independence. Obviously, that didn’t happen.

When the Civil War ended in a Northern victory, some Confederate currency was ”destroyed as waste paper, some was hoarded from sentiment or futile hope, and some was preserved as curios,” according to a 1947 numismatic guide.

There are a few places where these banknotes have been particularly well preserved. The Boston Athenaeum currently holds over 6,000 pieces of Confederate paper currency in its collection, with much of it viewable online.

The images also live on in remixed forms. South Carolina artist John W. Jones—himself a descendent of slaves—has created a series of colorful acrylic paintings based on the Confederate banknotes’ slavery vignettes, entitled “The Color of Money.” In his words, the images on the currency are “a visual smoking gun that documents how much free slave labor enriched America.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook