Object of Intrigue: Moche Sex Pots

Erotic pottery from the ancient Andean Moche civilization is the world’s most renowned…and explicit.

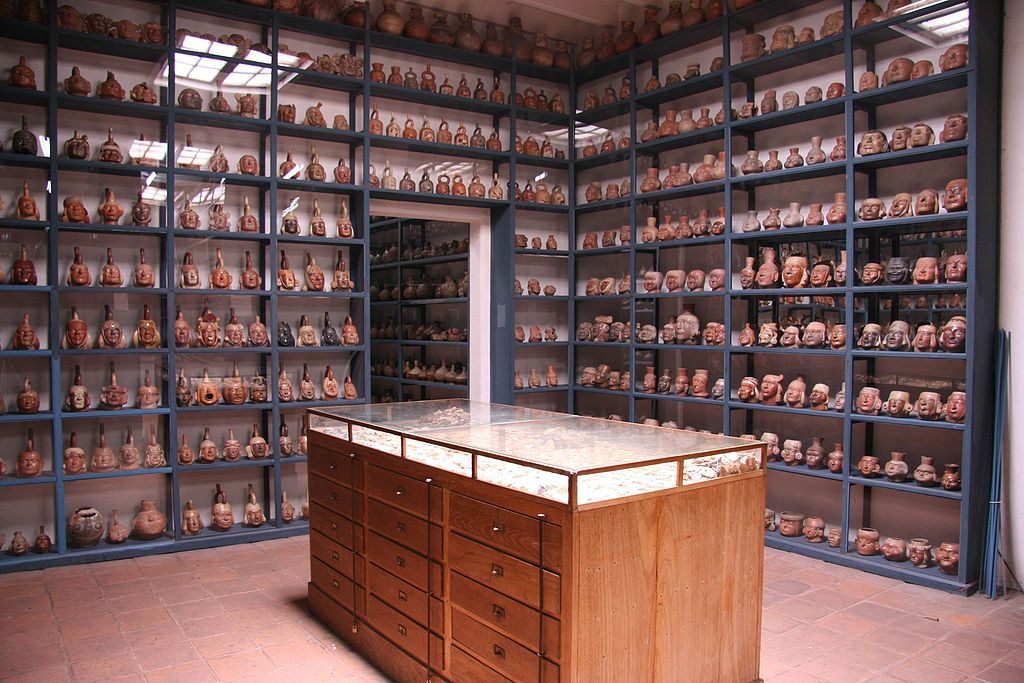

A pottery storage gallery at the Museo Larco. (Photo: Public Domain)

Employees at the Museo Larco in Lima, Peru are well-accustomed to flushed foreigners approaching timidly and asking, in hushed tones, “Excuse me, but where are the, uh, sex pots?”

We’ve all heard “sex pot” used to describe someone of significant sensual appeal. But these are literal sex pots: pottery depicting explicit acts, made by members of the ancient Andean Moche civilization.

While other pre-Columbian art collections also display sexual scenes, Moche erotic pottery is the world’s most renowned. The reason is simple. According to Northwestern professor of anthropology and sexuality studies Mary Weismantel, “Moche sex pottery is the largest and most graphic and explicit.”

The scenes of intercourse, oral sex, and masturbation on the pots could be ripped from the pages of an erotica novel written today, but, instead, they’re depicted on traditional ceramics sculpted over 1,500 years ago—in Peru, now one of the most conservative Catholic places on the planet. The Moche, who lived from 100 to 800 AD—pre-dating the more celebrated Inca— sculpted tens of thousands of ceramics, an estimated 100,000 of which remain. Of those, at least 500 are pots depicting sexual acts.

To the Spanish colonizers who uncovered Moche sex pots in indigenous spiritual temples and royal tombs scattered up and down Peru’s North Coast, the pieces were manifestations of something sinful. The Spanish were scandalized by the ceramics’ graphic detailing of sex between humans, skeletons, and animals—with infants also sometimes present as non-participants. Shaken to their Catholic core, they smashed the pottery to pieces and criminalized the premarital and non-reproductive sex acts depicted on their surfaces.

(Photo: Larco Museum Collection/CC BY-SA 3.0)

In the years, decades, and centuries following the arrival of the Spanish, hundreds more sex pots were dug up by looters and archaeologists, dispersing to private and public collections around the world. But the pots in Lima, housed at the bottom of the Museum of Archaeology, were kept under lock and key, reserved for only the most educated of eyes: those of social scientists and scholars. For the rest of the population, the erotic pottery was deemed far too provocative.

The Museo Larco collection is a little hard to locate. Segregated from the main exhibits, the sex ceramics are displayed in their own separately accessed gallery. When visitors do manage to track them down, they are met with raw, in-your-face three-dimensional sculptures, depicting scenes a lot more directly than they might have imagined. There is no euphemism here: men and women have anal sex, women perform oral sex on men, men masturbate. Meanwhile, “traditional” sex—that is, missionary-style vaginal sex for procreation—is almost nowhere to be seen.

Many ceramics also feature giant erect penises, sometimes sculpted into, fittingly enough, fully functional spouts for pouring liquid. Others show figures bearing rather goofy-looking grins. The sex appears pleasurable and unabashed. From Museo Larco’s sex pot gallery, it’s common to hear reactions escape in outbursts of gasps and giggles.

For Peruvians, though, these sex pots represent something more serious: a reality that cannot be reduced to mere iconography. To them, the story of the pottery might be symbolic of their own—a culture that has been devalued while at the same time appropriated for profit and for power.

Moche pots on display at the Larco Museum in Peru. (Photo: Rainbowasi/CC BY-SA 2.0)

As Caril Phang, a researcher of indigenous cultures of the Western Hemisphere, puts it:

That Moche pottery presented the physical act of sex was an affront to the Catholic faith. However, the art also proved advantageous to the colonizing ideal. It suited the Spanish need to define indigenous peoples as ‘carnal,’ ‘lustful,’ ‘pagan’ tribes on whom ‘just war’ would be declared, to expand Spanish territory—and the tenets of the Roman Catholic Church.

What the Spanish viewed as barbarian art, however, actually spoke of a highly organized civilization that in some ways might have been more socially and politically progressive than the one that centuries later came after it.

In some experts’ opinions, the sex ceramics could emphasize a sort of equality between men and women that is feminist in interpretation. Weismantel sees this in the representation of “their bodies, faces, tattoos, or body paint and adornments” which “are often shown as similar or even identical, so that they can be distinguished only by their genitalia.”

Other scholars believe the absence of vaginal sex in the pottery could also be indicative of another form of gender equality that gives women the same right to physical pleasure as men. By portraying women as in control of their own bodies, with their own sexual agency, the erotic ceramics might cast them as more than just future child-bearers whose value relies on their virginity.

The debate is heated, though, and other researchers disagree that there is anything about the pornographic pottery that would indicate Moche women were at all empowered. Scenes of female-administered fellatio, in particular, could represent the repressive society they faced.

Regardless, there is something markedly nonconformist about the Moche sex pots. “To my mind, the best things about these ceramics is that the more you look at them, the less they can be used to unambiguously reinforce any modern attitudes towards gender and sexuality,” says Weismantel. “They are just too different, and show us a picture of sexuality that does not conform to our expectations.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook