The Phantom Island That Haunted 16th-Century Newfoundland

The ‘Isle of Demons’ was said to be overrun with ghosts and ghouls.

Gales of wind gust in and out like the breath of an enormous beast as the storm begins on Quirpon Island, just off Newfoundland’s northernmost tip. The rain comes in sheets, soaking the isle’s emerald mesas and pebbling the icebergs that float offshore.

Other than the lonely lighthouse warning sailors from the jagged fangs off the island, Quirpon is barren. Except for the lighthouse’s caretakers and the odd visitor to the Quirpon Lighthouse Inn, none have willingly stayed on the island for long.

For close to 500 years, there have been rumors about what lies in this frigid, inhospitable corridor between Newfoundland and Labrador. Early Europeans were convinced that a massive landmass overrun with evil spirits jutted from the waters near Quirpon. Mariners called it the Isle of Demons.

The Isle of Demons appeared on maps of the New World for more than a century. But by the mid-1600s, cartographers made an important discovery: There was no Isle of Demons. It had never existed at all. Like the evil spirits that ran rampant over its rocky landscape, the island was a phantom.

Phantom islands have appeared on maps since the earliest cartographers surveyed their surroundings. They are geographical “belief features,” says Edward Brooke-Hitching, author of The Phantom Atlas: The Greatest Myths, Lies and Blunders on Maps, places that explorers, cartographers, and mariners were certain existed until time or technology proved otherwise.

“Sometimes these islands lived short lives before the error was corrected by vessels on confirmation missions, sometimes they lived their quiet lives of non-existence for centuries,” he says. Some even remained on maps into the 21st century.

Bermeja, a 31 square-mile island in the Gulf of Mexico first charted in 1539, was only officially marked as non-existent in 2009, following an investigation led by scientists from the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City.

Similarly, says Brooke-Hitching, “Sandy Island in the eastern Coral Sea [near New Caledonia] was first recorded by a whaling ship in 1876 and thenceforth marked on official charts for more than a century. It finally had its nonexistence established in November 2012, 136 years after it was first ‘sighted’ and a whole seven years after Google Maps was launched.”

There are a variety of ways that phantom islands make their way onto maps. Some are inspired by myths and legends like the phantom island of Hy-Brasil, once believed to have been located near Ireland (or, on some maps, shown closer to the Azores). Described as an Atlantis-like utopia of eternal happiness and immortality that emerged from the Atlantic only once every seven years, Hy-Brasil likely originated from concepts of the “Otherworld” in Irish folklore.

Despite no proof of its existence, the island remained on maps for more than 500 years, from 1325 until 1865.

The idea of the Isle of Demons was also rooted in myth, the sounds passing sailors heard which they mistook for imps cavorting in the fog. More likely, what they heard were not demons at all but “strange noises made by birds and other wildlife,” says Cynthia Smith, information resource specialist in the Geography and Map Division of the Library of Congress.

The treacherous waters between Newfoundland and Labrador and the extreme winter climate may also have played a role in the development of the island’s demonic identity. A countless number of ships have wrecked in the waters around Quirpon Island, says Ed English, owner of the Quirpon Lighthouse Inn and Linkum Tours, even after the lighthouse was installed in the 1920s.

“A lady in her 90s came from Texas in 2022 to visit the site of her grandfather’s shipwreck from over a century ago,” he recalls. “All the crew survived, but he died. It was presumed he drowned in the wreck, but his remains were found two or three years later. It turned out he had made it to shore and crawled up in the woods, where he then froze.”

While folklore has spawned many phantom islands, some are simply the result of honest mistakes. “Mirages and other visual phenomena have proven instrumental in manifesting the immaterial on maps,” says Brooke-Hitching, as has mismeasurement, especially before the invention of an accurate marine chronometer in the 18th century. “Errors were copied, and discoveries even frequently ‘remade,’” meaning that, in some places, a phantom was thought to be seen by more than one crew over time.

And then there are those phantom islands that have found their way onto maps fraudulently. In 1906, explorer Robert Peary claimed to have discovered an enormous landmass during an expedition across the frozen Arctic Ocean near Greenland. He named his “discovery” Crocker Land in honor of his financial backer, George Crocker.

But in his original diary, Peary makes no mention of finding land. He, in fact, explicitly writes that there was “no land sighted” on the date he claims to have seen Crocker Land, damning evidence that he made the whole thing up to please his benefactor. To date, despite valiant attempts to find it, Crocker Land has never been located.

While the Isle of Demons was most certainly a phantom island, one that was removed from maps in the mid-17th century, historical evidence suggests that it wasn’t completely nonexistent; an island in the Canadian North Atlantic was once called by its name. Odds are, the real Isle of Demons is the tiny, four-mile-long by two-mile-wide Quirpon, which was given its modern name by the French sometime later, between the mid-16th and mid-18th centuries.

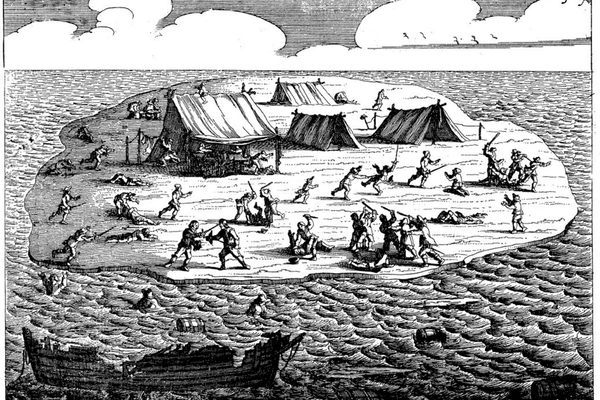

In 1542, French noblewoman Marguerite de La Rocque was forced to spend two lonely years on the so-called Isle of Demons. While accompanying her uncle to the French colony at present-day Quebec, de La Roque became romantically entangled with one of the ship’s sailors. Incensed, her uncle deposited the young woman, along with her handmaid and lover, on the “Isle of Demons.”

Neither the sailor nor the servant lasted long. Both, along with the baby de la Rocque birthed there, died within months. But De la Rocque survived, spending almost two years on the island. Eventually, a passing French fishing boat rescued and returned her to civilization.

Although there’s some question as to whether Marguerite de La Rocque’s island prison was located where the 16th-century map placed the Isle of Demons or further south in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, her story has become embedded in the history of Quirpon Island. Smith believes there’s a good reason for that.

“In my opinion, the Isle of Demons [where De la Rocque spent two years] was more likely to be Quirpon Island because of its location,” she says. “I think Marguerite de La Roque would have been rescued earlier if the island was in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.”

Many visitors to the starkly beautiful island need no convincing of Quirpon’s role in de la Roque’s tragic story. Some even believe the spirits of the dead still roam its tablelands. “We’ve had staff and guests who were certain they had seen the ghost of Marguerite,” English admits.

But whether little Quirpon Island is indeed the monstrous Isle of Demons that appeared on maps between 1508 and the mid-1600s, no one knows for sure. Phantoms, by nature, prefer not to be found.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook