On Vacation in Soviet-Era Sanatoriums

The treatments are no longer mandatory, but they’re still available.

In 2015, writer Maryam Omidi found herself in Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, during a trip across Central Asia. She was only a short distance from Khoja Obi Garm, a Soviet-era sanatorium that specializes in radon water treatments. She found herself strangely smitten, “in awe of the architecture, the treatments and the hospitality … The more I read about sanatoriums, the more fascinated I was by them.”

Two years later, after visiting 39 sanatoriums across 11 former Eastern Bloc countries, and after a successful crowdfunding campaign, Omidi and London-based publisher Fuel released Holidays in Soviet Sanatoriums. Omidi worked with eight different photographers who specialize in the region to capture both the architecture and the people who still visit these once-popular—once-state-mandated—vacation destinations.

In 1920, Lenin issued the decree “On utilizing the Crimea for the medical treatment of working people.” The Labor Code of 1922 formalized mandatory vacations, and throughout the Soviet years, sanatoriums were built on the Crimean Peninsula and around the USSR. “Sanatoriums were a mix between medical institution and spa,” explains Omidi, in an e-mail. “Soviet citizens stayed at sanatoriums for at least two weeks a year, courtesy of a state-funded voucher, as part of the ‘work hard, rest hard’ ideology of the time.”

On first arriving at a sanatorium, a guest would consult with a doctor, who would then prescribe a series of treatments. In the early years of the sanatoriums, everything was rigidly scheduled—even time spent sunbathing. “Rest and recuperation at sanatoriums did not involve idly lolling about, but instead consisted of a schedule of different treatments and exercises that in the early days was quite rigidly upheld,” says Omidi. “Although sanatorium culture relaxed over time, in the 1920s and 1930s, visitors went without their families, and weren’t allowed to drink, dance, or make too much noise. The idea was that it was a time for contemplative reflection on socialist ideals and an opportunity to reenergize before returning to work.”

The idea was also that everyone would derive the benefits of the sanatoriums, and that this would create a healthier and more productive workforce. With vouchers, called putevki, guests could stay either for free or at a subsidized rate, at a predetermined destination. However, these ideals didn’t always live up to the reality. “In practice,” writes Omidi in the book’s introduction, “the best accommodation usually went to those with money and connections.” Some sanatoriums, such as at Kyrgyzstan’s Aurora, took this preferential treatment a step further. Aurora was built in 1979 specifically for the Soviet elite, and had more than 350 staff for 200 guests.

Sanatoriums were constructed throughout the Soviet Union right up until its collapse in 1991, which explains the wild range of architectural styles among them. Khoja Obi Garm, the site that first intrigued Omidi, is a tiered, brutalist slab of concrete hewn into Gissar Mountain Range. Ordzhonikidze, in Sochi, Russia, is neoclassical in style and palatial in proportions, with a fountain, pool, and outdoor cinema. It was built in 1936, in the era of Stalin’s purges, and is named after an associate of Stalin’s who later died under mysterious circumstances. Reshma, which opened in 1987, is a red-brick monolith near the Volga River, about 300 miles northeast of Moscow. Its guests included cosmonauts and those impacted by radiation exposure at Chernobyl.

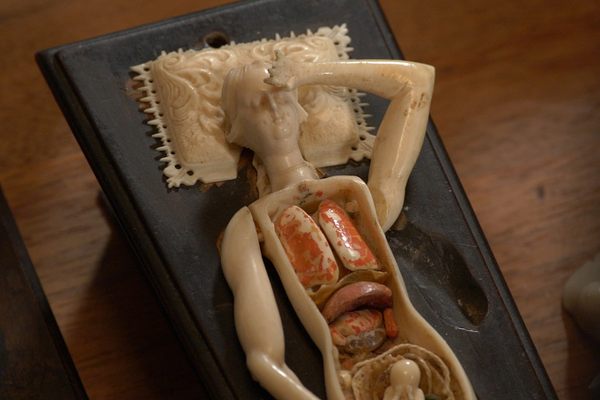

Nearly all of the sanatoriums featured in the book still offer a range of treatments—some more unusual than others. One particularly startling entry is the National Speleotherapy Clinic just outside Minsk, Belarus. Speleotherapy is a form of respiratory treatment that involves breathing inside a cave. In this case, that cave is a salt mine nearly 1,400 feet underground. While it does offer some facilities on the surface, the consultation rooms, activity areas, and dormitories are all situated in tunnels. According to the book, more than 7,000 children and adults visit each year.

Omidi was most surprised by the crude oil treatment at Naftalan, in Azerbaijan, a “petroleum spa town.” The oil found at Naftalan has specific properties that are supposedly beneficial, though some experts argue they’re more likely carcinogenic. “Crude oil of differing levels of purity is used for everything from bathing to gargling with,” Omidi explains. “Although it feels pretty luxurious to be in a bathtub full of crude oil, the whole experience is quite slippery so not the most graceful.”

Today, a night’s stay at the Soviet-era Chinar sanatorium in Naftalan costs about $112. (There are 11 sanatoriums in Naftalan, but only one that predates 1991.) Other sanatoriums, like the exclusive Aurora in Kyrgyzstan, can reach $200 per night during the summer. According to Omidi, some of the visitors today treat the sanatoriums more like hotels, to take advantage of their proximity to beaches, for example. “Others take them much more seriously, returning annually to treat certain ailments or to undergo treatments as a prophylactic measure.”

Regardless of the reasons for a visit to a sanatorium, “vacation” is a different concept today than it was in Soviet Russia. As metal fitter S. Antonov wrote in a newspaper column in 1966, “I receive my vacation once a year and I try not to waste a single day of it in idleness.”

Atlas Obscura has a selection of images from Omidi’s book below.

This story originally ran on October 5, 2017.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook