How a Guatemalan Town Tackled Its Plastic Problem

In San Pedro La Laguna, single-use items made from plastic and styrofoam are banned.

At dawn, the market is bustling with all the usual suspects. A vendor prepares tostadas with an array of colorful toppings from sautéed beetroot to homemade guacamole. In the next stall, a woman is pounding out blue corn tortillas by hand—the rhythm of her labor echoes throughout the market, setting a lively tempo. Nearby a farmer is selling fresh produce from wicker baskets.

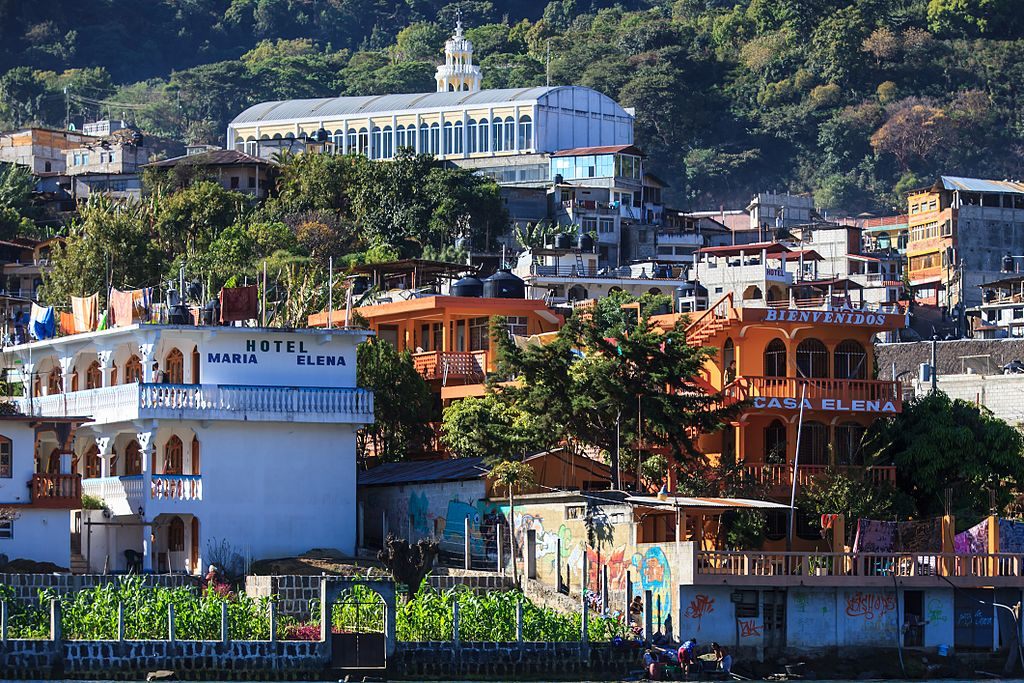

Inhabitants of San Pedro La Laguna are primarily Tz’utujil Maya. Local ladies don colorful textiles, carrying the history of their ancestors in the threads. They carry equally bright woven rubber basket bags that they fill to the brim with goods. The baker and pharmacist are busy handcrafting paper packaging for their products. Men wearing traditional woven hats sit on the shallow steps of the town’s Catholic church as children play in the stark white courtyard.

Something is missing from this commerce scene: single-use plastic and styrofoam.

Before 2016, San Pedro La Laguna was drowning in plastic pollution that was threatening the fragile ecosystem of Lake Atitlán. The dire need for change crystallized when a solid waste disposal processing plant that was expected to manage a decade of waste was halfway full within six months, mostly with single-use plastics. Rather than build a larger plant—which would’ve been an enormous financial burden on the town and further polluted the lake with debris—Mayor Mauricio Méndez decided to implement a stringent municipal law to encourage lasting, sustainable change.

Méndez took unprecedented measures and established a zero-tolerance policy, banning single-use items made of plastic or styrofoam including bags, straws, and containers. San Pedro La Laguna was the first town in Guatemala to enact such a drastic ordinance against waste.

Villagers initially resisted, as they’d become accustomed to using materials that were now outlawed. To get rid of the single-use plastics already in circulation, leaders of the 13,000-person town went from house to house to talk with villagers about waste management. Residents were wary because they couldn’t afford to purchase biodegradable replacements. The government relieved the community members’ financial burden by collecting all plastic and styrofoam items and trading them for reusable or biodegradable alternatives, completely free-of-charge.

Victor Tuch Gonzáles, the municipal planning director, says eliminating the use of plastic bags was the biggest hurdle. To alleviate this issue, the municipality purchased 2,000 handmade rubber basket bags from artisans in Totonicapán to distribute among families. Gonzáles says the switch to reusable items, including the bags, cost the municipality 90,000 GTQ ($11,632).

Economic sanctions punish anyone who breaks the law. Individuals must pay 300 GTQ ($40)—a hefty amount considering Guatemala’s average lower-middle-class annual income is $1,619. Companies that use the banned materials face a fine of 15,000 GTQ ($1,940).

The town also needed a better system to process waste. According to Gonzáles, Cementos Progreso and the Pro Verde NGO process the town’s trash into fuel or other derivatives. Local fisherman joined the sustainable efforts and created their own initiative to remove garbage from Lake Atitlán. Several projects have launched to transform trash into decorations which encourages the mentality of reducing, recycling, reusing, and regenerating.

Gonzáles says that the ideology has “returned to what was used ancestrally.” The community has returned using hoja del maxán (large leaves) to package meat from the butcher and cloth napkins to carry tortillas. Vendors wrap items in paper as if plastic had never tormented the town. Once the reusable rubber bags have been filled to the brim, ladies stash dry goods in their aprons.

Some businesses are starting to use paper straws. Gonzáles prefers to avoid any single-use items, as he sees no reason not to drink straight from the can, bottle, or glass. Gonzáles jokes that “you don’t need a straw for beer, so why use one for soda?”

By restoring and preserving the natural beauty of the lake, San Pedro La Laguna has attracted more tourists. Tourism is the largest economy in San Pedro La Laguna—visits to the town increased by 40 percent in 2018. Travelers are also prohibited from using plastic bags, straws, and styrofoam containers in the town.

Méndez and Gonzáles hope their efforts will be replicated by other townships on Lake Atitlán in order to align preservation efforts and honor Mother Earth—a significant figure of Mayan spirituality. The ecological municipality is developing additional environmental conservation projects including residual wastewater treatment plants, switching to LED lights, prohibiting sand extraction from the lake, and using waste as building materials to build tables and chairs for local schools. Gonzáles believes that these efforts will “have a positive impact not only on the environment but also the economy of local people.”

As Méndez says, “tu basura es mi fortuna”—your trash is my fortune.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook