This Startup Is Transforming Used Chopsticks Into Beautiful Furniture

Humans throw out more than 80 billion pairs a year.

For more than 5,000 years, chopsticks have been the preferred dining utensil of a sizable swath of humanity. Nowadays, around a third of the global population uses chopsticks daily. This is both a fact of life and, given these implements are often single-use, a serious environmental problem.

Every year, around 80 billion pairs find their way to landfills. Activists in China, by far the world’s largest producer, have documented rates of deforestation as high as 100 acres a day in order to keep up with demand. For years, the Chinese government has levied taxes on manufacturers and promoted reusable chopsticks. Yet the problem persists, primarily because the disposable options made of aspen, birch, and bamboo are so eminently practical.

“In Vancouver alone, we’re throwing out 100,000 chopsticks a day,” says Felix Böck, founder of the Vancouver-based startup ChopValue. “They’re traveling 6,000 or 7,000 miles from where they’re manufactured in Asia to end up on our lunch table for 30 minutes.”

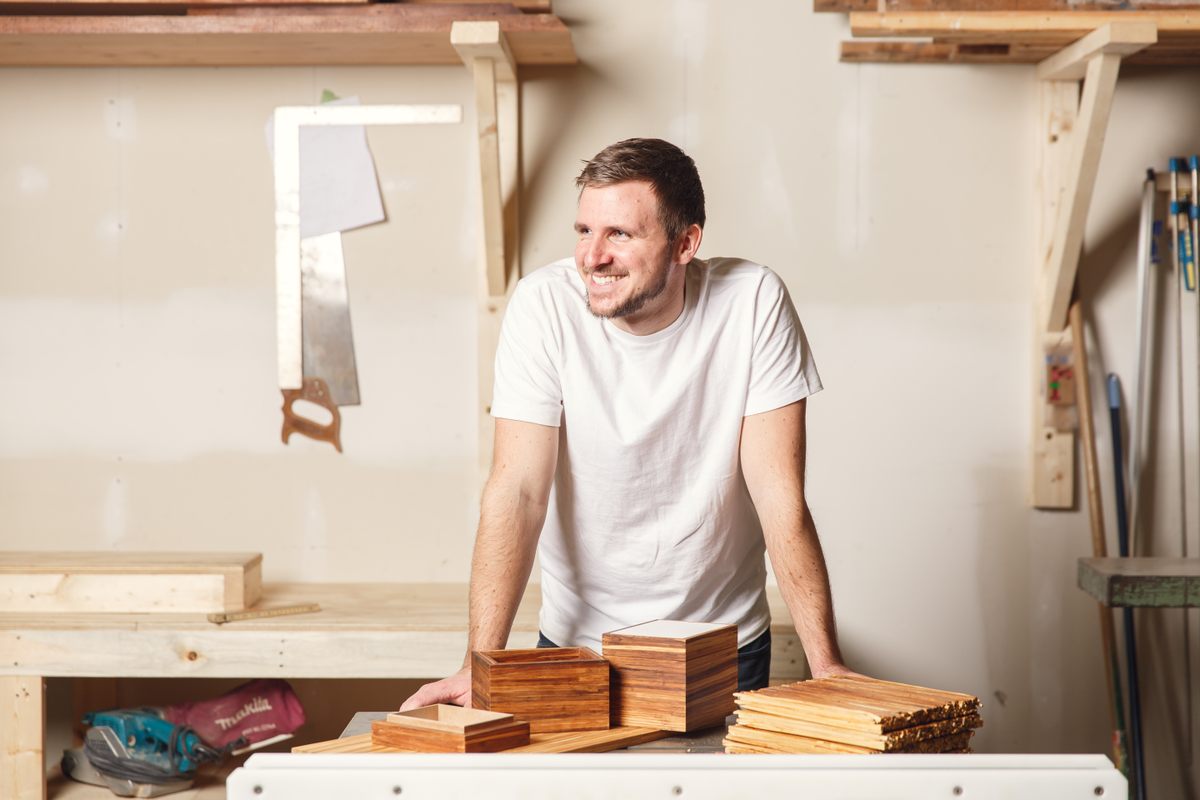

Since 2016, Böck has been on a mission to rethink disposable chopsticks. Rather than try to eliminate them, the engineer has been building a circular economy by giving them a second life. In their homebase of Vancouver, company staff pick up around 350,000 used chopsticks from 300-plus restaurants every week, all of which become book shelves, cutting boards, coasters, desks, and custom decorations. According to Böck, the startup has saved more than 50 million pairs of chopsticks from landfills since its launch.

“Once you see the volume, you think maybe that little humble chopstick can be the start of something big,” Böck says. “My expertise is in bamboo, so I always looked at chopsticks differently. I used to joke to my friends that I would make something out of chopsticks, since most of the ones we use in North America are made of bamboo.”

Transforming a teriyaki sauce-slicked piece of bamboo into a rolling cabinet takes quite a bit of work. To remove any trace of food waste, the chopsticks are first coated in a water-based resin, then sterilized at 200 degrees Fahrenheit in a specialized oven for five hours. A hydraulic machine then breaks the wood down into a composite board, which is sanded, polished, and lacquered as necessary. “This material is then the core piece for everything from desks and table tops to home decor,” Böck says.

Sleek and highly functional, each piece of furniture has a negative net-carbon impact. While the casual observer might not realize their desk is the product of thousands of sushi orders, ChopValue’s team intentionally leaves in aesthetic hints for those who look closely. Interested consumers can also see the exact impact of each piece of furniture they purchase—a work desk, for instance, consists of 10,854 discarded chopsticks. In some cases, the circular loop is conspicuously short; Pacific Poke, a fast-casual chain that has a partnership with ChopValue, transforms the chopsticks used by its own customers into wall decorations and tables for its outlets.

For ChopValue to be more than a novelty, Böck knows that it needs to scale. The company recently received $3 million in funding and, in 2021, launched its first international franchise in Singapore. “We’re trying to expand responsibly and chose to franchise the concept so that other business owners could own their own microfactories,” he says.

Chopsticks are far from the only disposable dining implement to come under scrutiny in recent years. From plastic straws to polystyrene takeout containers, many components of our food cycle sacrifice environmental impact for convenience. Without sweeping legislative change, most of these items are unlikely to disappear anytime soon.

“I think change starts small, and change can be a very relatable thing that we all know from daily life,” Böck says. “Right now, we’re focusing on the chopstick because it’s a very powerful story, but I think there are so many other urban resources where we can make this work.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook