The Church Where Robots Come to Life

(Photo: Chico MacMurtrie/ARW)

(Photo: Chico MacMurtrie/ARW)

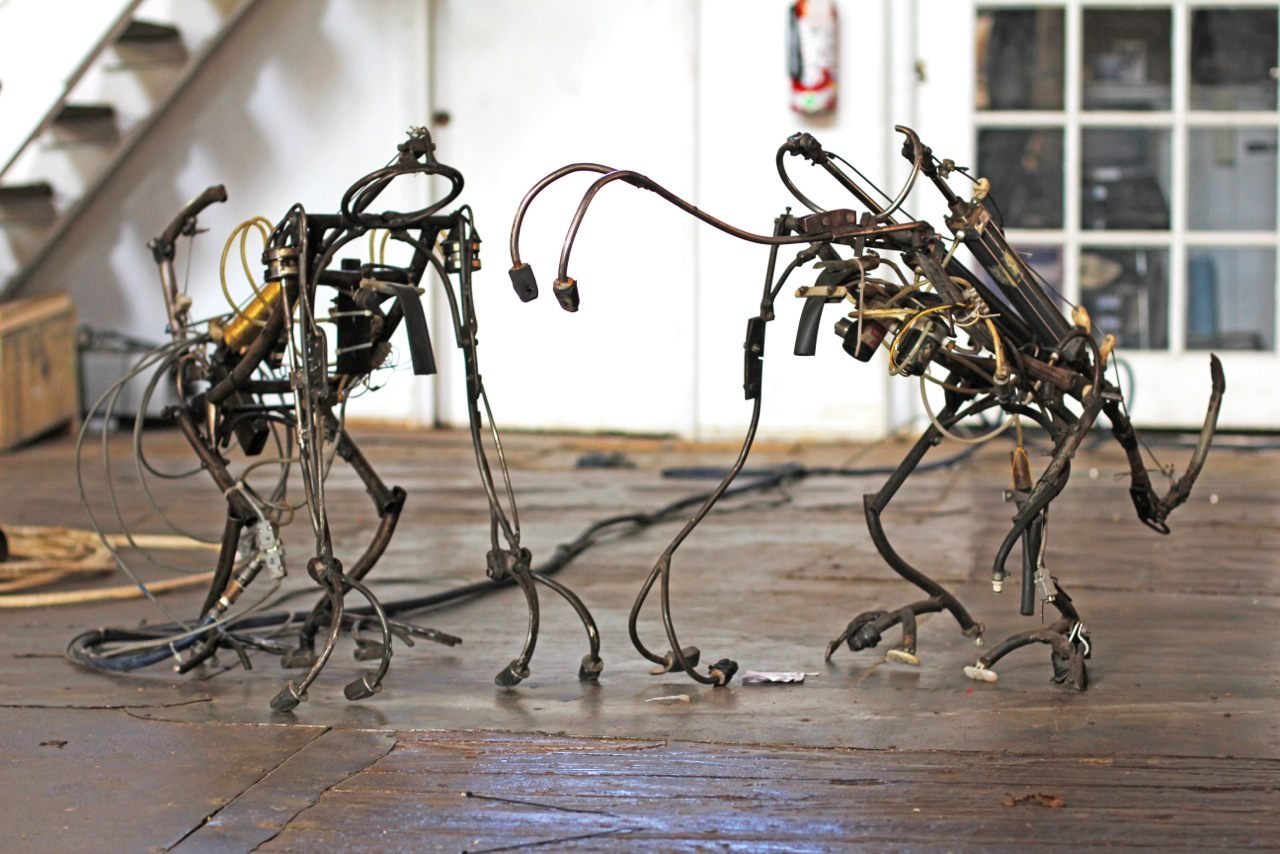

Before they settled in the Robotic Church, among squat brick rowhouses on a quiet street in Brooklyn, Chico MacMurtrie’s creations traveled the world. The Tumbling Man lost a foot in a cobblestone square in Pilsen, in the Czech Republic. In Sao Paulo, Brazil, the Rope Climber scaled a five story building until one day, he fell, and had to go into surgery, at the aluminum shop, the machine shop, and the welder.

“He got put back together better than ever,” says MacMurtrie. “They invited him to stay for another month. He went up and down the tower on San Paulista, the main boulevard. He climbed that building every day.”

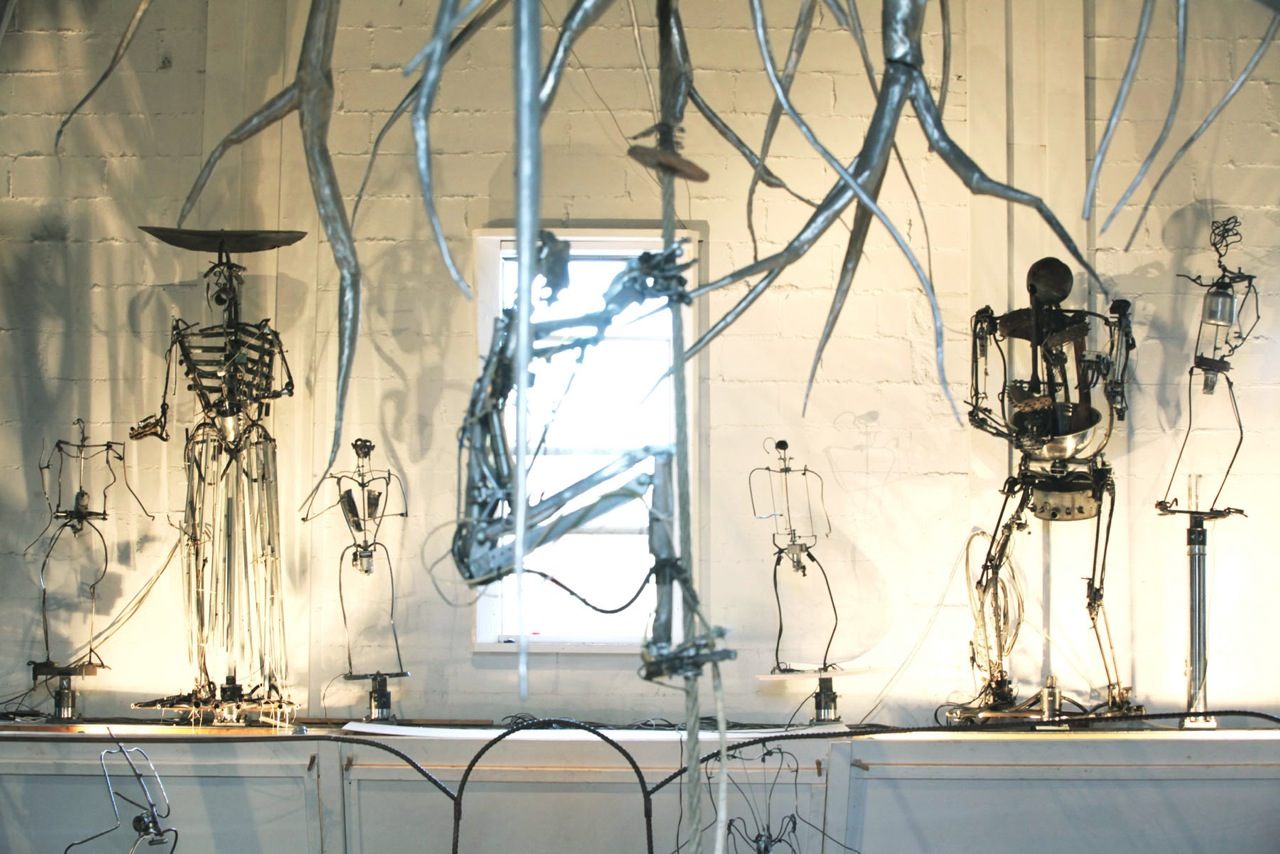

The robots performed together, touring in shows titled the Ancestral Path and the Robotic Landscape. In one, they lined up along a road of sorts, where robotic dog-monkey machines would visit them; in another, when an individual machine performed, it would be lifted above the audience to “solo.”

After their last tour of Europe, in 2006, the denizens of the Robotic Church were placed in storage. But four years ago, MacMurtrie started thinking about transforming a church space that he had used as an art studio into a more permanent home for his creations. When they arrived, “I sensed that they were really comfortable being here,” he says. “They’re set in a place where they can be seen, and they’re all close enough to each other that they can have a relationship.” In 2013, they performed together for their first New York audience.

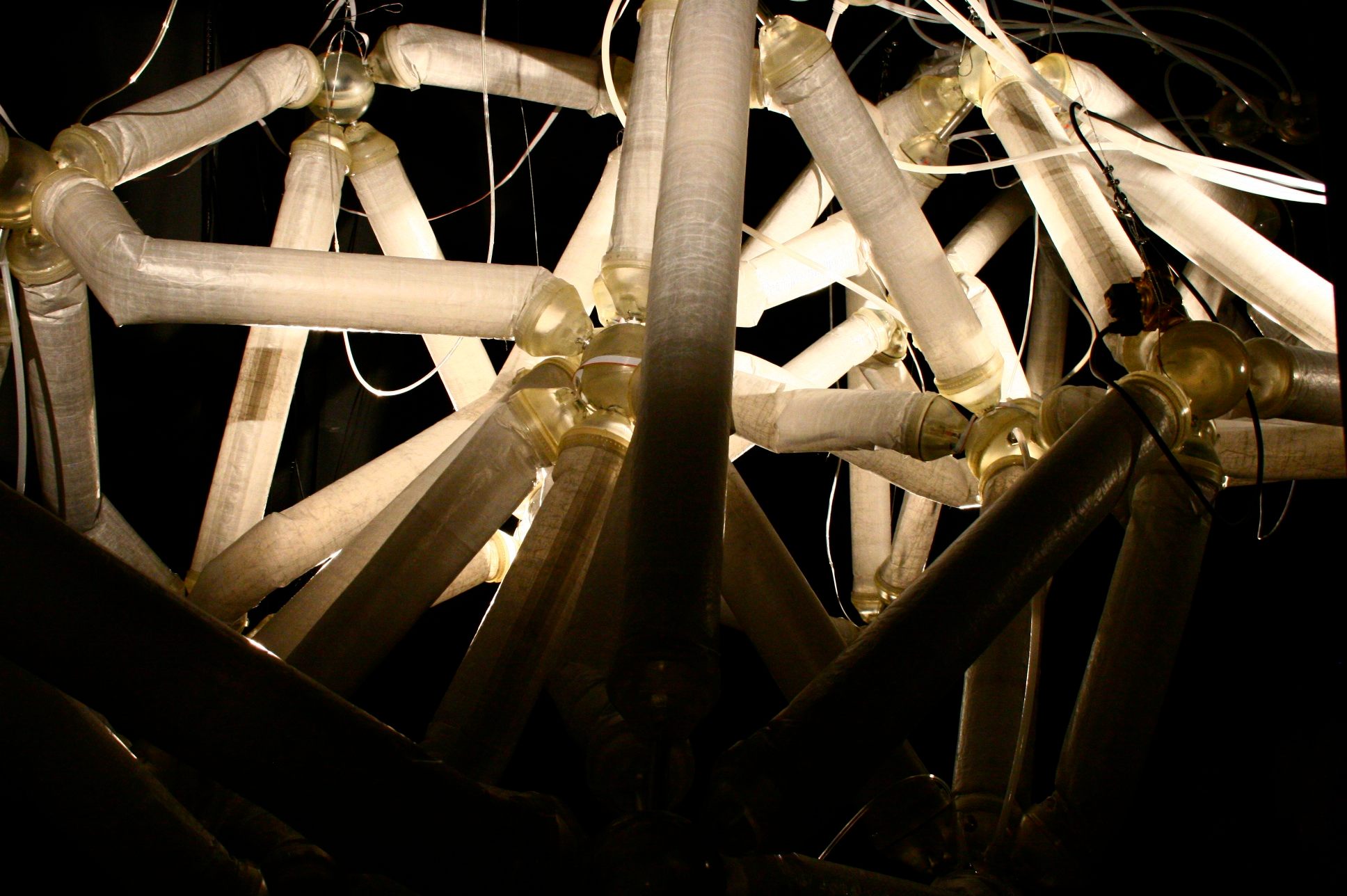

The Robotic Church, 2013-2014. (Video: Chico MacMurtrie / ARW)On an afternoon in May, MacMurtrie and his assistant, Zhongyuan Zhang are in the backroom of the studio working on a mechanism of ropes and spools that will make one of his latest projects move. The piece consists of a series of opaque tubes, shaped into vertical waves, that can inflate and deflate. “What we want to happen is that when they’re drawn together and deflated, they’ll be a gathered mass. You can’t see the pattern,” he explains. “When you expand it, it grows outwards more.”

The idea, he says, is to push the piece to the maximum that it can do, without hurting it. “For me, it’s about a performative moment, where something occurs that’s visually stimulating,” he says. He’s imagining that a person would walk in, see the piece, drawn together, and wonder what it might be. “And then it opens up, and it changes form, in a more fulfilling way,” he says.

In 1987, when MacMurtrie was working on his first robots, few artists were making these kind of machines. Now, art students can take classes in robotics, Google’s headquarters are being built to by robot-crane hybrids, and emotionally intelligent robots can take your picture. But unlike robotics being built to perform functions, he builds robots that simply perform, not just for humans, but with them. “My medium, really, became doing performance with machines,” he says.

MacMurtrie’s characters don’t necessarily move fast or smoothly, but they are strangely endearing in their efforts to move in a human-like way. While big corporations are making increasingly skilled robots that seem like they could take over the world, “I’m the other guy,” says MacMurtrie, “who’s trying to express something about humanity and what technology is doing to humanity.”

Two of MacMurtrie’s dog-monkeys. (Photo: Mathew Galindo/Courtesy of Chico MacMurtrie/ARW)

The Primitive Squatting Man, the first machine MacMurtrie created, was made out of a door-dampening cylinder, the type of gizmo that keeps a door from slamming. That was the machine’s muscle. MacMurtrie coaxed it into standing up, tapping its belly with a stick, and rolling its eyes. That alone took a long time. But, he says, ” there was something really powerful with imbuing this metal and junk stuff with a life force.”

Before he starting making machines, MacMurtrie had studied art, dance, theater, sculpture, and music. It was his own body, he says, that taught him first about proportion, muscle, bone and structure; he moves with the care of a stage performer, and when he talks, his hands activate, pointing with the index finger or spreading out to carefully define the space between them

Each robot he developed has its own “one liner” gesture—the awkward, clunking Tumbling Man tries to somersault like a child, the Taiko Drummer rolls his hand across the skin of a drum. Another throws rocks.

“They’re maybe at their best strength, when they run all together,” says MacMurtrie, “because it’s a society of machines. They have a commonality and ancestry. They’re communicating through their body language and expression and the sounds they make. They’re linking the music that’s in us to the gesture that’s in us.”

A drummer. (Photo: Chico MacMurtrie/ARW)

MacMurtrie first came to New York in 2000, after the landlord of the space he was working in the Bay View neighborhood of San Francisco tried to triple the rent, in the wake of the dot-com boom. MacMurtrie’s mother had recently died, too. It seemed like the right time to try New York.

His first spot in the city was small. But a friend knew the owner of an unusual space in Brooklyn, an old Norwegian sailor’s church. Together, they went to see the space, and it was a wreck. There was trash piled to the ceiling, holes in the floor, holes in the roof, and squirrels and raccoons making themselves comfortable.

The friend wasn’t interested. So he helped MacMurtrie score it. Part of the deal was that he became responsible for the space, and when he received a grant from the New York Council for the Arts, he used it to throw away all the garbage, fix up the place, and create a working studio. He’s been here now for 14 years.

Since he’s worked in this space, MacMurtrie has shifted from making metal, humanoid robots to soft, inflatable robotic sculptures. After creating a piece called Skeletal Reflections, which could copy the gesture performed by a human being, he felt like he was reaching the limits of working with metal.

“While that character was capable of pretty interesting gestures, it still can’t match the quality of flesh, when our flesh meets our flesh,” he says, pushing his hand against his face, and softening his skin into wave. “Our frown, our sorrow is depicted through the gesture of our skin. So is our happiness. That was the turning point, where I thought I really want to go after this notion of all of those components being inflatable.”

Chrysalis, Pioneer Works, Center for Art and Innovation, 2013 (Video: Chico MacMurtrie / ARW)In the side room of the church, some current projects sit collapsed into a heap, like a pile of intestines. To the touch, the material feels like a raincoat. On the side table sits a board gridded with small metal box—the valve and computer system that will run a piece called the Border Crosser.

Lately, MacMurtrie and his family have been spending more time in Arizona, where he grew up. In the morning, he says, everything is lit with incredible light. At night, seven miles in the distance, they can also see the lights of the border fence. “The ranch is right at the border with Mexico, and this project, Border Crossers, is completely tied into growing up in Arizona, and my relatives having immigrated legally, because they were skilled workers.”

MacMurtrie’s father ran a stallion ranch, and his uncles worked there as cowboys. “This generation, the border has just become a conflict to spend money on,” he says. “The notion of the Border Crosser is—this is a gesture of peace between these two countries that are one and the same.”

He imagines that six fabric piles would be dropped off at particular locations, three on one side of the border and three on the other. “They would simultaneously grow, and bend over the border at the same moment,” he says. “And that would happen for however long we could let it happen.”

In a sense, the same time frame applies to the Robotic Church. Brooklyn is changing, getting more expensive, and if MacMurtrie and his charges had to leave this space in the Red Hook neighborhood, it’s not entirely clear where they would go. For now, though, the robots will continue to spend their time together, occasionally giving concerts, for however long that can happen.

The Robotic Church. (Photo: Eve Sussman/Courtesy of Chico MacMurtrie/ARW)

Inflatable Architecture (Photo: Chico MacMurtrie/ARW)

What is Obscura Day? It’s more than 150 events in 39 states and 25 countries, all on a single day, and all designed to celebrate the world’s most curious and awe-inspiring places. To get ticket information on the Robotic Church’s concert on Obscura Day, go here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook