The Ghost-Busting ‘Girl Detective’ Who Awed Houdini

As an undercover investigator, Rose Mackenberg unmasked hundreds of America’s fake psychics.

Rose Mackenberg started as a believer: In the early 20th century, the American public seemed to be in a state of continuous mourning. In just a few years, World War I and the Great Flu of 1918 had claimed nearly 800,000 American lives. The environment of grief provided a fertile ground for the movement known as Spiritualism, and its practitioners gained huge followings by claiming they could communicate with the dead.

In the early 1920s, Brooklyn-born Mackenberg was working at a detective agency in New York when she was assigned a case about a psychic who had recommended worthless stock to a local banker. A mutual friend introduced her to magician Harry Houdini, who was then waging his own crusade against Spiritualists. At the peak of his career, Houdini had decided to use his spotlight to denounce a practice he just couldn’t stomach: psychics who preyed on the bereaved. He’d recently announced a $10,000 reward to any medium who performed a feat he could not replicate with various well-known tricks.

Impressed by Mackenberg’s detective skills, he offered her a job as an investigator helping him unmask Spiritualist con artists. She hesitated: Personally, she believed communication with the world beyond was possible. This job, Houdini replied, would be a great way to test that.

Houdini himself had sought solace in Spiritualism after losing his beloved mother, Cecelia Weisz, a decade earlier. In one seance he listened as the medium relayed a long and dramatic letter allegedly written by his mother—in English, a language she never spoke.

When Houdini was just starting out as a performer, he and his wife Bess had included a medium act in their stage show. But he had grown disillusioned by seeing how it affected those in mourning with false hope. His disillusionment turned to anger; then his spiritual yearning turned into a kind of crusade for justice. But few Spiritualists would let themselves be confronted by him—Houdini was simply too famous—both as a magician and “spook-baiter,” as Mackenberg once called him. By the time he hired Mackenberg, she joined a staff of around 20 investigators. She quickly became the most renowned among them.

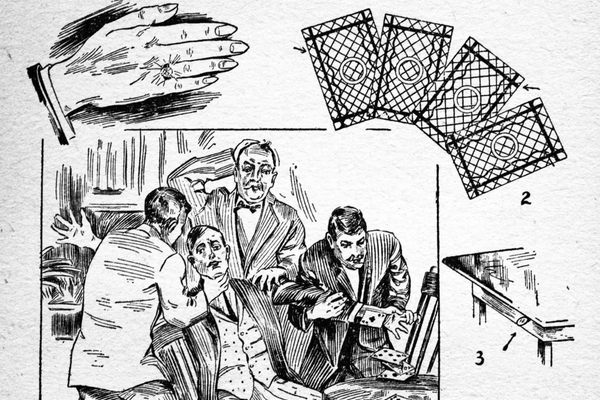

Here’s how it worked: Mackenberg traveled ahead of Houdini’s tour, scouting local mediums and con artists for the magician to later unmask on stage. She lingered at department stores and read through the local papers to suss out the town’s psychic-types. She then selected a new identity and ventured into their seance rooms.

Her disguises ranged from “small-town matron” to “credulous servant girl,” to “a ‘vamp’ from the country.” A 1929 profile of Mackenberg, “Houdini’s Mysterious Girl Detective,” in the Minneapolis Star Tribune, showed a photo of the investigator sans disguise. “Observe the sharp, unwavering gaze and the firm chin characteristic of all skilled sleuths,” the caption read. In an interview, she described the backstories she and the other investigators made up in those dark back rooms. “The more fantastically improbable the story, the more apt was the medium to fall for it,” she said.

In Chicago, she dressed as a widow named Rosalind Richards and paid a visit to prominent Spiritualist pastor Herman Parker. After he claimed to connect with her fake dead husband, Mackenberg decided to test the limits of his deception. She asked Parker for the spirit’s advice on what she should do with the settlement she was offered for his death. Parker advised she invest it in a company called Wilcox Transportation Company—a scheme, of course, run by Parker and his accomplice. Mackenberg turned over her findings to the Investors Protective Bureau and Parker was jailed for fraud.

Once Mackenberg had gathered information about a fraud and turned it over to Houdini, he would publicly call out the con artist from the spotlight of his show. Often Mackenberg would take the stage to describe her visit, and prove she’d been in the medium’s house by providing details—and even a secret marking she’d left as proof. If a medium refused to back down, a volunteer committee would escort the person to their home to find her sign: a seven-pointed star drawn in green crayon on the wallpaper. It wasn’t entirely uncommon for the shows to end in brawls, with Houdini’s investigators as the targets.

In Indianapolis, Mackenberg posed as a mother who’d just lost her infant, for a visit to self-proclaimed Spiritualist leader Charles Gunsolas. Gunsolas offered her the ability to communicate with the spirit world via a bowl of water for $25 (several hundred dollars in today’s money), and encouraged her to remove her clothes to improve the line of communication. Six weeks later, during a performance in Indianapolis, Gunsolas sat in the audience of Houdini’s show. Houdini revealed his fraud and Gunsolas was booed out of the stadium.

By 1926, news of Houdini’s crusade and Mackenberg’s cunning had reached every corner of America. Congress was holding a hearing on whether to ban fortune telling in the nation’s capital, a rare city in which they could actually be licensed. Houdini led the charge, but the papers were fixated on his accomplice.

Mackenberg’s testimony was explosive: She reported that senators frequently visited mediums in Washington, and named four of them, from Indiana, Kansas, Washington, and Florida. Then she revealed that one medium swore that President Calvin Coolidge had attended seances held at the White House. (It wouldn’t be the first time: Mary Todd Lincoln reportedly invited psychics to the White House to attempt to make contact with her deceased son.)

“Spiritualists in Clash Over Bill With Magician,” headlines proclaimed. The hearing was raucous, with Houdini taking the stand to expose how their tricks were performed, and offered $10,000 on the spot to any medium who could prove their contact with the dead. In their testimony and protests, Spiritualists claimed that the ban would stifle their religious freedoms. At one point, the session “came near winding up in a free-for-all fist fight,” The New York Times reported.

The bill was eventually shot down by lobbying from the Spiritualist community and the Coolidge administration denied holding seances.

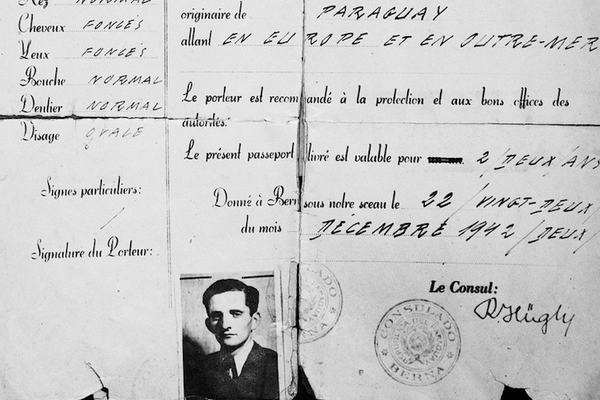

By that time, Mackenberg had investigated some 300 mediums. In the course of her investigations, she had been ordained as a Spiritualist minister six times, and the other investigators had taken to calling her the “Rev.” This honorific even made it into press: in the New York Daily News coverage of the Washington trial, she’s referred to as “the Rev. Rose Mackenburg [sic] of the High Spiritualist church.” She told reporters of the fun she had inventing pseudonyms when getting ordained, with names such as “Allicia Bunck”—a play on “all is bunk”—or F. Raud.

The headline-making hearing would be the end of her work with Houdini, who died five months later, at age 52. But Mackenberg carried on their mission. For three more decades, she investigated mediums on behalf of private citizens, insurance companies, banks, and other clients. But that didn’t necessarily change her view of the afterlife.

“I am not a skeptic, despite all the imposters I have uncovered,” she told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1937. “I would be the first to acknowledge a message from the Great Beyond if I were convinced that it was genuine.” However, she said, before Houdini died, they had made a pact: If it were possible, he would make contact with her from the afterlife. “I have never as yet received the slightest semblance of a bona fide message along the lines upon which we agree.”

By the time she died in 1968, she claimed to have investigated 1,500 mediums. “Rose Mackenberg dons shabby clothes and tracks down ‘spirit world’ frauds,” the Vancouver Sun wrote of her. “She has found plenty, too, having been put in touch with 1,500 departed husbands she never had.”

Nina Strochlic covers stories about migration, conflict, and interesting people across the globe. She was previously a staff writer for National Geographic, Newsweek, and the Daily Beast. She cofounded the Milaya Project, a nonprofit working with South Sudanese refugees in Uganda.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook